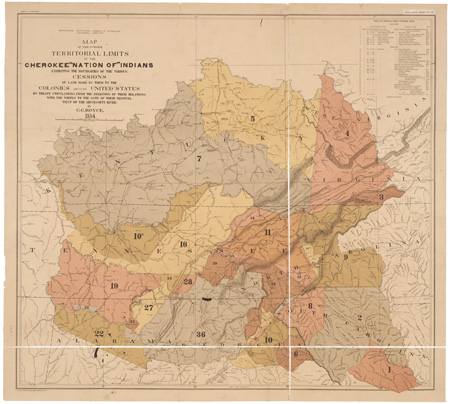

I’ve spent the past few days looking again at some of the 3,200+ maps digitized for our North Carolina Maps online collection. And, curiously, I keep coming back to the map above. I think one of the reasons is the information at the upper right of the map, Numeric and Chronologic Schedule of Cherokee Cessions (click on the closeup below to see the details).

The list extends to 36 entries on this map and if you look on a second map there are another 11 entries (Sorry, we don’t have the second map up. It covers land west of North Carolina and didn’t fit the criteria for our NC Maps site). I’m surprised at the number of treaties and land deals. Perhaps I shouldn’t be.

I started wondering about the person who meticulously documented the numerous land cessions. The name C.C. Royce is found just below the map’s title. It’s a shortened version of Charles C. Royce. Royce was an Ohio native. In 1863, just a few months shy of his 19th birthday, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy and spent the last months of the Civil War aboard a Union river monitor. After the war he joined the Office of Indian Affairs as a clerk. Royce’s work on Indian land cessions drew the attention of John Wesley Powell, the first head of the Bureau of Ethnology. Powell helped Royce with his study of the Cherokee, checking books out for him from the Library of Congress and providing him money for research trips. In 1883 Royce was appointed to a position as ethnologist on the Bureau’s staff. But a year later, he returned to Ohio to work as an accountant at the Miami County Bank.

Before leaving Washington, Royce submitted a monograph about his research on Cherokee land cessions for inclusion in the Bureau’s annual report. In a letter he wrote, “Of course I never had any conceit that in a strict sense of the term it belonged among scientific papers. It is purely historical and yet I am constrained to believe that the ‘popularity’ of a work such as the report of the Bureau of Ethnology, would not be abridged in the mind of the average reader by having a little politico-Indian History sandwiched between their ‘myths’ and ‘stone implements’ on the one side and their ‘sign language’ and ‘mortuary customs’ on the other.

In 1888 Royce became manager of Rancho Chico, a California fruit ranch. He retired in 1912 and died in Washington, D.C. in 1923.

Royce’s monograph The Cherokee Nation of Indians was reprinted as a book in 1975. In an introduction, Richard Mack Bettis, president of the Tulsa Tsa-La-Gi-Ya Cherokee Community, writes that the Cherokee owe a debt of gratitude to Royce. His “accurate reporting on treaties and boundaries” provided the data that helped the Cherokee over many years to win more than $14 million in legal claims for land taken illegally from the nation.