This Month in North Carolina History

Boyd Payton’s mind raced with questions as he steered his car back to his Charlotte home after a Sunday visit with a friend on June 14, 1959. An announcer on the radio station to which he was tuned had just identified him as one of eight people charged with conspiring to blow up an electrical sub-station and textile manufacturing facilities in Henderson. Although Payton, the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA) regional director for the Carolinas, had spent plenty of time in Vance County in the previous months negotiating on behalf of workers at the Harriet and Henderson Mills, several of the individuals listed as his co-conspirators were unknown to him. But, in the ensuing weeks, he would become well-acquainted with them and the tactics state and local officials were willing to use to bring to an end the strike-related violence crippling Henderson.

Payton’s arrest followed more than eight months of tensions in Henderson. Members of TWUA Locals 578 and 584 went out on strike in November 1958 after the owner of the Harriet and Henderson Mills, John D. Cooper, Jr., refused to accept a new contract that called for arbitration of union grievances

Initially, the strike was peaceful. Union members picketed outside the locked gates of the mills, which Cooper had closed in response to the strike. But, as late January approached, workers grew increasingly frustrated with management’s refusal to return to the bargaining table. Community leaders, too, grew edgy, concerned that the strike would hinder Henderson’s ability to attract new industries. And local businesses began to complain of lost revenues.

In early February, company officials decided to resume production. Before reopening the mills, they sent recruiters into communities throughout North Carolina and Virginia to find potential strikebreakers. Management also sought legal means to prevent strikers from preventing a new workforce from entering the plants. On February 9, with management’s encouragement, a local businessman crossed the picket lines with a load of cotton. As the man’s truck approached the factory gates, strikers surrounded it and pulled the driver from the cab. The incident sparked a Superior Court judge to issue a temporary restraining order barring strikers from interfering with “free ingress and egress” to and from the mills. The judge also limited the number of pickets to eight, ruled that picketers had to stand at least seventy-five feet from mill gates, and ordered that strikers direct no “vile, abusive, violent or threatening language” toward managers or strikebreakers.

Tasked with upholding the judge’s orders, local law enforcement appealed to the state for help. In response Governor Luther Hodges, a former textile executive, sent 30 members of the State Highway Patrol to Henderson. The state troopers were on guard February 16 when the mills reopened with newly-hired workers and some strike-breaking union members. Two nights later several bombs exploded in the mill villages. One explosion took place in the yard of a Local 584 member who had returned to work. The blast caused little damage and no injuries. And, although those responsible were unknown, many blamed strikers. But Payton of the TWUA suggested that the violence might have been instigated by forces seeking to discredit the TWUA and justify the continued presence of the State Highway Patrol in Henderson.

There was additional violence several days later. On February 23 Cooper announced that the company would hire permanent replacements for those who hadn’t returned to work and that any new contract would grant strikebreakers seniority over strikers. Shortly after Cooper’s announcement, Payton reported being clubbed unconscious in his hotel room by a group of attackers. The next day, February 24, several picketers threw rocks at strikebreakers’ cars. In response, state troopers began escorting strikebreakers into the mills.

The Highway Patrol’s increased role in protecting strikebreakers led Payton to accuse state officials of siding with Cooper and his company. But Hodges argued that state law enforcement only was seeking to maintain order. When bombings, vandalism and other violence continued through February and into early March, Hodges sent the SBI to investigate. Suspecting union involvement in the violence, agents put Payton under surveillance. But the SBI’s investigation failed to produce quick results and the violence continued, with continued bombings and street battles occurring between picketers on one side and the highway patrol and strikebreakers on the other.

On March 3 Hodges sent an additional 100 members of the Highway Patrol to Henderson, a move that put a total of 146 troopers in the city and resulted in one-quarter of the statewide force being based there. Hodges also prodded the Cooper to make concessions. When negotiations failed to produce results, Hodges chose to personally intervene. He called for both sides to meet with him in Raleigh.

Continued negotiations under the governor’s supervision produced an agreement on April 17. The proposed contract stipulated that arbitration would occur with the mutual consent of the union and management. Workers would also retain the right to strike if the company refused arbitration. Negotiations also produced agreement that strikebreakers would retain all first-shift jobs, but remaining shifts would be filled by strikers.

But the agreement was short-lived. It unraveled when strikers learned that management had only retained 30 jobs for them and had given the remainder to strikebreakers. Accusations that management had negotiated in bad faith were followed by additional violence. Facing criticism for his use of the Highway Patrol, Hodges ordered the state troopers replaced by the National Guard in May. Henderson took on the look of a town under military occupation as several hundred soldiers with bayonet-tipped rifles arrived to maintain peace.

Also in early May a special session of superior court was held to try those arrested for violating the restraining order. More than 60 union members and sympathizers were convicted and given jail sentences, fines, terms on county road gangs or some combination of the punishments.

Payton and his co-defendants appeared for trial in July. The state’s case against them rested on testimony from Harold Aaron, a textile worker and union member from Leaksville in Rockingham County. Aaron had moved to Henderson to find work as a strikebreaker. Union officials hoped to use him as a spy inside the mills. But, unbeknownst to them, he was also working as an informant for the State Bureau of Investigation. Under the direction of the SBI, Aaron met with several strikers in a bugged motel room in Roanoke Rapids, about 30 miles from Henderson. Prosecutors contended that Aaron and the strikers discussed blowing up the offices and a boiler room at the Harriet mills and destroying an electrical substation that provided power to the plants. According to the prosecution the plotters agreed to meet again on June 13 to carry out their plan. When the group assembled that evening, SBI agents rushed in to arrest them. No dynamite or other explosives were found.

Both the prosecution and the defense agreed that Payton was not present at the June 4 meeting, nor was he among the group arrested on June 13. But the state argued that Payton had knowledge of the conspiracy because of a telephone call on June 4. On that evening Aaron telephoned a Henderson hotel room that TWUA officials were using as an office. Payton answered the phone, acknowledged that he knew Aaron and then said, “Don’t say too much over this phone—it is going through a switchboard.” Payton and his attorneys argued that union officials offered such warnings to all callers because the hotel in which they were staying was owned by the Cooper family. Furthermore, they added, Payton’s comments were insufficient evidence of participation in a conspiracy.

Despite the defendants’ claims of entrapment a jury returned guilty verdicts on all charges. The judge sentenced Payton and two other regional TWUA officials to six to ten years in prison. The five strikers received slightly lesser sentences. The eight defendants immediately appealed their convictions and remained free on bail as their cases wound their way through the appeals process. Hodges declined to grant pardons or commute the defendants’ sentences. When the N.C. Supreme Court denied the appeal, Payton and his co-defendants petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court. But the high court refused to hear the case in October 1960. Shortly thereafter Payton and his co-defendants began serving their prison sentences.

As Payton and his co-defendants settled into prison life, newspapermen and others campaigned for their release. Supporters included Charlotte Observer columnist Kays Gary, Carolina Israelite publisher Harry Golden, Raleigh News and Observer editor Jonathan Daniels, Raleigh minister William W. Finlator Sr. and evangelist Billy Graham. In addition to penning articles, the group wrote letters to Terry Sanford, who became North Carolina’s governor in January 1961. Their efforts eventually paid off in July 1961 when Sanford reduced the defendants’ sentences. The governor’s action made four of the men immediately eligible for parole. A fifth had already been paroled. Payton and his two TWUA colleagues were required to wait until August for parole. Three years later, on New Year’s Eve 1964, the day his term as governor expired, Sanford granted a full pardon to Payton. The governor declined to do the same for the remaining seven, noting that the evidence against Payton was different and insufficient to support the verdict.

By the time he received his pardon, Payton had ceased working for the Textile Workers Union of America. The Henderson strike, too, was over, having ended on May 26, 1961, when the TWUA’s executive council in New York voted to call an end to protests. The strike brought no concessions from Cooper, in effect allowing management to destroy the TWUA locals. Most of the strikers never worked another day in the Harriet and Henderson mills. And the memories and divisions created by the unrest in Henderson plagued the city for years.

Suggestions for further reading:

Cartwright, Perry. “The Henderson Trial: Will the Trial of Textile Union Leaders Break the Back of Southern Unions and Make the South Safe for Industry?” Southern Newsletter 4.1 (August-September 1959): 0-3

Cater, Douglass. “Labor’s Long Trial in Henderson, N.C.” The Reporter Sept. 14, 1961: 36-40.

Clark, Daniel J. Like Night & Day: Unionization in a Southern Mill Town. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Payton, Boyd E. Scapegoat: Prejudice/Politics/Prison. Philadelphia: Whitmore Publishing Co., 1970.

The Henderson Story. Henderson, N.C.: Harriet and Henderson Cotton Mills, 1961.

Image Sources:

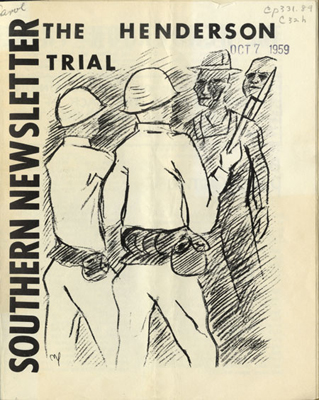

“The Henderson Trial.” Cover of Southern Newsletter, in North Carolina Carolina Collection.

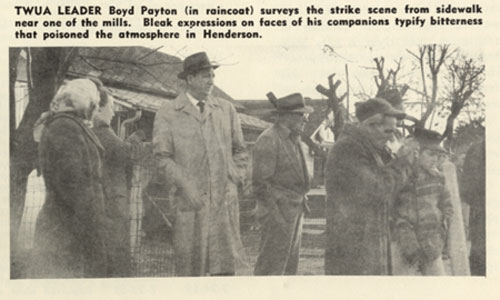

Boyd Payton and strikers from “The Henderson Story,” a compilation of articles on the Harriet and Henderson strikes from America’s Textile Reporter magazine. Republished by Harriet and Henderson Cotton Mills, in North Carolina Collection.

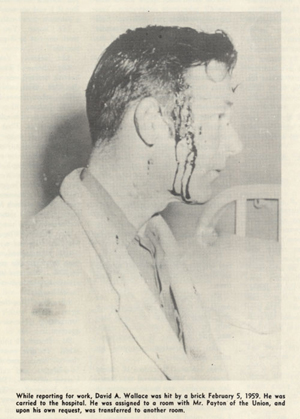

Bleeding man from “The Henderson Story,” a compilation of articles on the Harriet and Henderson strikes from America’s Textile Reporter magazine. Republished by Harriet and Henderson Cotton Mills, in North Carolina Collection.