This silk curtain from the North Carolina Collection Gallery dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. It hung in Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s carriage but somehow ended up in the hands of a Union private in mid-1863. To know the story, read on…

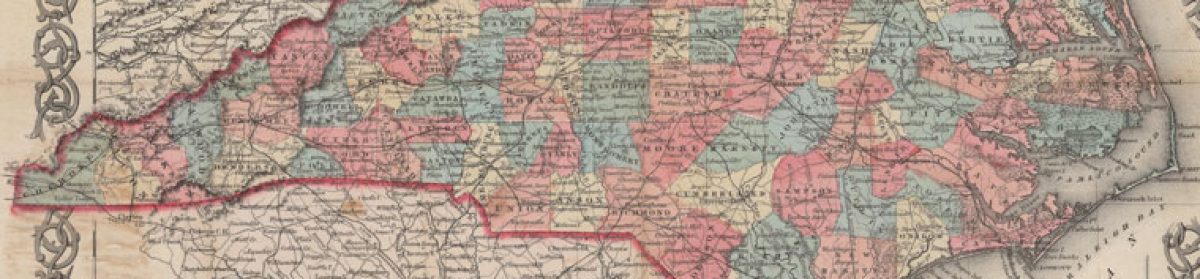

As mentioned in the post about the Braggs of North Carolina, Braxton Bragg of Warrenton began his service for the Confederate States Army in Louisiana. On February 6, 1861, he was appointed commander-in-chief of Louisiana’s state army with the rank of brigadier general. A month later, Bragg assumed command of the Confederate holdings at Pensacola, Florida. After the onset of war with the Battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, more soldiers arrived in Pensacola, and Bragg was in command of nearly 7,000 troops needing to be organized and trained. Bragg’s work with the new soldiers impressed President Jefferson Davis, who sent some of the troops to Virginia and replaced them with new volunteers needing training. According to Samuel J. Martin’s General Braxton Bragg, C.S.A., the Secretary of War promoted Bragg to the rank of major general in October and expanded his command to the holdings at Mobile, Alabama.

In February 1862, Confederate forces withdrew from Pensacola as Federal troops continued to attack. Bragg and his 10,000 troops were sent to the Mississippi-Tennessee border where General Sidney Johnston and his regiments were marching after engagements with Union Generals Grant’s and Buell’s armies. Confederate Generals P.G.T. Beauregard, Leonidas Polk, and William J. Hardee also marched to the area of Corinth, Mississippi. There, Bragg was named one of the three leaders of the Army of Mississippi, and he was also appointed chief of staff with the responsibility of training the troops. On April 3, 1862, the Army of Mississippi headed northward into Tennessee. The Battle of Shiloh began on April 6.

Considered a Union victory, the two-day battle resulted in a total of over 1,700 dead and 8,000 wounded as well as thousands of missing. Nevertheless, at its end, President Davis promoted Bragg to the rank of general, making him one of seven to attain the rank within the C.S.A. After moving his troops to Chattanooga, Bragg marched north into Kentucky. On October 8, 1862, Bragg’s troops fought in the Battle of Perryville. Considered a victory in different ways for each side, there were over 500 Confederate dead, over 2,600 wounded, and 250 captured. Bragg had failed to push the Federal forces out of Kentucky, but a few weeks later, President Davis gave Bragg control of the Department of East Tennessee. Bragg then assumed the role of head of the Army of Tennessee.

Bragg established his headquarters at Murfreesboro. On December 31, 1862, his troops engaged with those of Union General Rosecrans in the Battle of Murfreesboro. After 10,000 of his soldiers were killed, wounded, and captured, Bragg ordered a retreat south to Tullahoma nearer the Alabama border. Outspoken criticism of the general was widespread throughout the citizenry of the C.S.A. as well as the officers and other men of the army. In response, Bragg sought to reorganize and ready his men for another campaign. President Davis wanted to remove his old friend from the command of the Army of Tennessee, but this did not happen due to a variety of circumstances. In late June 1863, General Rosecrans sent his army into central southern Tennessee to battle again with Bragg, who was convinced to fall back further south in order to better protect supply lines. As Rosecrans pursued, Bragg decided on July 2, 1863 to retreat further south for a better tactical position. Disliking the position, Bragg then ordered his troops to march eastward to Chattanooga, giving up central Tennessee to the Union.

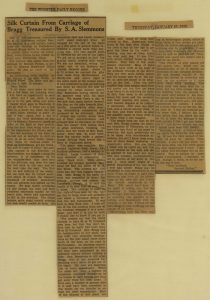

On July 5, 1863, Union Private Samuel Patton wrote a letter to his wife, Nellie, in which he states: “Gen. Bragg in his hasty retreat was compelled to leave his private carriage and retreat on horseback, though it is said his health is so poor that he looks like a ghost. The carriage is built in the style of those used by the ‘upper ten’ in large cities and probably cost about a thousand dollars before the war commenced. It was built in New York City. I took off one of the silk curtains from one of the windows, wrapped it in a newspaper, and sent it to you by mail. I should like to know if you get it.” Nellie did indeed receive the silk curtain, and Patton’s nephew, S.A. Slemmons, inherited it. On January 20, 1938, The Wooster Daily Record in Ohio published an article (shown below) including a transcript of the letter. Slemmons’ great-grandson William Race, a professor in the Department of Classics here at UNC, later inherited the curtain and donated it to the North Carolina Collection. The curtain’s dimensions are 19″ x 23″. It has survived for almost 150 years, and its incredible story adds to the strength of the collection here at the NCC.