Twin City residents this past weekend celebrated the 100th anniversary of the consolidation of Winston and Salem into one municipality. The joining of the two towns in 1913 was a long time in the making. As Frank Tursi writes in Winston-Salem: A History, in 1879 the town boards in Winston and Salem appointed a special committee to study consolidation. That group recommended uniting the towns as the City of Salem. Both town boards approved the charter and it was ratified by the General Assembly. Salem residents voted overwhelmingly in favor of consolidation. But people in Winston voted against consolidation.

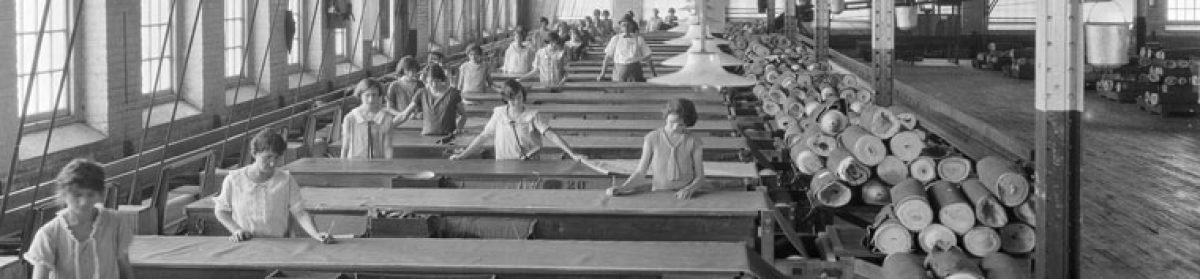

When the vote was taken, Salem was the larger and more influential of the two towns. It had a long and storied history and have provided land and much of the leadership for Winston’s founding. But the days when it could control the direction its stepchild took were coming to a close. As it grew and honed its industrial muscle, Winston began to overshadow its parent. It took control of Salem’s destiny.

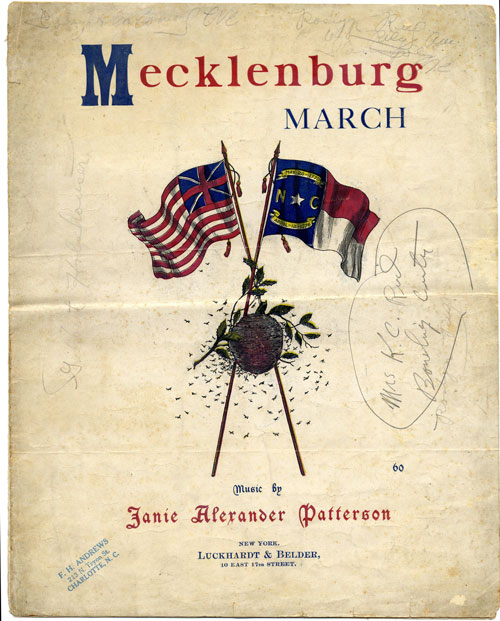

During the 1890s postal authorities sought to close the Salem post office and consolidate it with the Winston branch, under the name Winston. In 1891, when such a move was proposed, Salem’s mayor Henry E. Fries pleaded his town’s case in Washington, D.C. and managed to save the post office. When the postal service pushed again to close the Salem branch office in 1899, Fries managed only to wrest from authorities assurance that the consolidated branch would operate under the name Winston-Salem. According to Tursi, many had referred to the two towns in that manner for some time. “But the hyphen took on permanence when it started appearing in postmarks,” he writes.

In December 1912 Winston business and civic leaders decided to push again for consolidation. They prepared a merger plan and submitted to the General Assembly a petition with 1,705 signatures in support of the idea. State legislators agreed to the plan on January 27, 1913 and a vote on merger was scheduled for the two towns on March 18. Consolidation proponents realized that they needed to build support for their plan in Salem. They appointed Fred Fogle, the 28-year-old mayor of Salem, as the leader of their efforts in that community.

Fogle found his job difficult. He spent his time countering rumors, unsigned circulars and insinuations made against him and the leaders of Winston. Some suggested that Winston would have more representatives in town government. Proponents responded that representation would be apportioned equally based on population. Salem would become a ward and have two alderman for its 5,700 residents. Winston would be divided into three wards and have six alderman for its 17,000 population.

Recalling that period in an article published on the 50th anniversary of consolidation, Twin City Sentinel City Editor Bill East wrote:

Salemites raised the question of whether hog-raising would be permitted in the new town. Knowing that it was risking alienating many who raised them, Winston admitted frankly it would not.

Moravians hit hard at the liquor question. They said that the merger of the towns would be the forerunner of making a ‘liquor town’ out of Salem. Winston replied that it had no intention of doing so and that statewide laws covered the liquor question adequately….

Circulars were passed around saying that the community’s old Moravian traditions would be abandoned and that Winstonites would ‘contaminate the moral welfare of the people to the point of wreckage….’

At one point near the climax, the campaign got so heated that a report circulated in Salem that the new city had plans to ‘dig up’ Salem Cemetery after consolidation.

This struck Moravians on one of their tender points—their respect for the dead. Salem town officials, who favored the consolidation, found it necessary to officially deny the report. ‘Someone evidently had a nightmare,’ the denial said.

Josephus Daniels, editor of the Raleigh News and Observer, compared the consolidation campaign to a courtship and impending wedding.

The bride-to-be, Miss Salem, feels that in learning, in the love of music and the arts, she is the superior of the groom, Mr. Winston.

Secretly the groom admits it, but the bride is proud of her intended’s splendid spirit…And now shortly there is to be a vote to determine whether the wedding is to take place and instead of two sets of officers, Winston-Salem shall be married for better or for worse.

The bride-to-be had stipulated that she will not give up her maiden name and lose her identity—if there is to be a wedding after all, the English hyphenated custom must prevail…after marriage the union must be called Mr. and Mrs. Winston-Salem.

On March 18, 800 Winston residents voted for consolidation and 260 voted against it. In Salem the margin was closer, with 385 in favor and 224 opposed.

Though voters had approved consolidation, the two towns didn’t officially join together until May. On May 6, Oscar B. Eaton, who had served as mayor of Winston from 1901-1911, was elected mayor of Winston-Salem. And on May 12 Eaton and eight alderman gathered in Town Hall on the site of the present day Reynolds Building to take the oath of office. “Mr. Winston” and “Miss Salem” were now officially a hyphenated union.