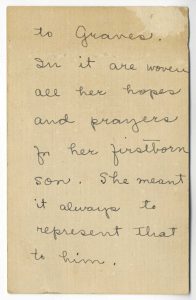

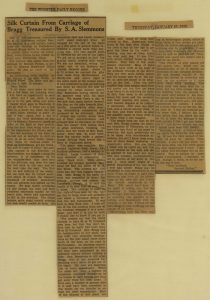

This newspaper article mentioned in the July Artifact of the Month post contains the transcript of a letter written by Union Private Samuel Patton to his wife, Nellie. Published in The Wooster Daily Record in Ohio on January 20, 1938, Patton’s letter includes many observations and details about his surroundings in 1863 central southern Tennessee. To make the letter easier to read, we have transcribed it below:

July 5, 1863

Dear Nellie,

I sit down once more to write you a few lines, not knowing when I will have an opportunity to send a letter, but I can write it and put it in the post office and when a wagon train goes to Nashville it will go with it. I wrote you a few lines in a hurry the other day but I don’t know whether it went or not, it was dated July 1, but it makes but little difference at any rate as General Rosecrans issued an order on the 22nd of June prohibiting the mail from being taken out of his department for fifteen days.

On the morning of the 22nd we started out at daylight to drill an hour or so as usual before breakfast, when we received order to pack up immediately, get our breakfast and be ready to move. We soon after started in the direction of Murfreesboro, our brigade taking the advance. It is customary to let the brigades each take their turn in the advance, and then the next day fall back in the rear and let the next take the lead. The first day we saw nothing of the enemy, but the next day we turned south, and about 10 o’clock the frequent discharge of artillery announced that our advance had stirred up the enemy. We kept slowly advancing all day though the road had been rendered extremely muddy by the heavy rain, which had commenced to fall in the morning. The firing became quite rapid toward evening but had nearly ceased at dark. An occasional shot was heard, however, until about midnight when we camped for the rest of the night on a flat piece of ground which resembled a swamp more than anything else. The rain poured down in torrents all the rest of the night. We got up at daylight to find the ground nearly covered with water. We ate our breakfast, wrung the water out of our blankets and started forward again. About 10 or 11 o’clock we reached the pike that leads from Murfreesboro to Shelbyville and about eight or ten miles south of the former place. It had continued to rain all morning and when we reached the pike we camped to await further orders, Gen. Rosecrans having moved out on another road with his main army. We stayed there a day or two and then again moved forward, this time on the pike toward Shelbyville. Immediately after starting, skirmishing commenced, and increased as we advanced. About 5 o’clock our cavalry drove them out of their entrenchments and pursued them to this place, by which time the enemy were falling back in great confusion, thinking, no doubt, that the whole of Gen. Rosecrans’ army was at their heels. Here the cavalry made a general charge, driving them before like a flock of frightened sheep.

The panic was complete. Our cavalry captured their stores, five hundred prisoners, and a battery of artillery. Large numbers of them were drowned in attempting to swim Duck river, while others crowded the bridges, pushing each other off into the water, 20 or 25 feet below. The citizens say the scene was one that beggars description. Gen. Bragg in his hasty retreat was compelled to leave his private carriage and retreat on horseback, though it is said his health is so poor that he looks like a ghost. The carriage is built in the style of those used by the ‘upper ten’ in large cities and probably cost about a thousand dollars before the war commenced. It was built in New York City. I took off one of the silk curtains from one of the windows, wrapped it in a newspaper, and sent it to you by mail. I should like to know if you get it.

The citizens say that the rebels claimed to have 60 or 70 thousand men here, but that they don’t believe that he really had more than 20 or 25 thousand. Gen. Bragg had his headquarters at this place, had built very extensive fortifications on the pike about three miles north of the town on the road to Murfreesboro. An immense amount of labor had been expended on them but they were abandoned on our approach almost without striking a blow. Gen. Rosecrans is still after Bragg, who at last accounts was straining every nerve to get out of his reach. His men are deserting him at every opportunity. When the rebels left here, a number of conscripts concealed themselves in the houses of their friends and thus got away from the rebel army. I have seen a number of persons who it is said have been concealed in the woods for six months to escape the rebel conscription. Most of the citizens of this place are Union, and many of them have friends in Gen. Rosecrans’ army. Some of the boys were diving in the river a day or two ago to get guns lost there by the rebels in crossing, and one of them found the rebel mail bag. It was filled with letters written home by their soldiers. They were of the most gloomy character. Most of them seem to have little or no hope of the ultimate triumph of the South. They say they must finally submit and they sooner they do so the better, as they are bound to be whipped in the end. They tell their families that they cannot send them any money nor can they get away to go home to do anything for them. In fact, they seem to see nothing ahead but want and the certainty that their families will sooner or later become beggars or be reduced to starvation. How men can fight with such a future staring them in the face, and from which no good can possibly result to them from it, is more than I can imagine.

The people here say that by the time Gen. Bragg crosses the southern boundary of Tennessee, he will have lost one third of his army by desertion, but such predictions are to be taken with considerable allowance, but still I know large numbers of them desert whenever an opportunity offers. But one thing I think can be relied on, and that is our armies in the west will not be allowed to fool away any more time this summer, notwithstanding the ill success of our army in the east I have more hopes of a speedy termination of the war than I ever had before. Bragg may be retreating to some stronghold in the south where he hopes to fight Gen. Rosecrans and have all the advantages on his own side, but I have the utmost confidence in old ‘Rosa.’ The rebels have been in the habit of calling him ‘the dog Rosecrans.’ I think before they get through with him they will find he combines the qualities of the bulldog and bloodhound with the cunning of the fox. I think he will fight Bragg as long as Bragg has the vestige of an army.

Everything here has been selling at extravagant prices, calico at from three to four dollars per yard, coffee six dollars per pound and everything else in proportion. I saw a man today wearing a pair of shoes that he said he paid $45 for. They would cost about two dollars and a half in the North.

The Fourth of July passed off very quietly here. There was no demonstration at all to remind an American of our national birthday. We had camped outside of the town but moved in yesterday and took up our quarters in a large three story brick building. The lower story had been used for a store, but our boys occupy the entire building from the counter to the lower shelf behind it. On these we spread our blankets and in short, so far as appearance goes, live quite aristocratic for soldiers. I received a letter from you on the 4th, dated June 18. I had not received any for some time, I believe the last one before that was dated the 6th or 7th of June, but perhaps it was well enough I didn’t get any before, for if I had known Minnie was sick I should have been very uneasy.

Morning, July 6. A train of wagons starts for Nashville this morning. It was the 23rd instead of the 22nd of June we started from Trynne. I can’t tell you when we will leave here, but will write again the first opportunity I have. I got my paper and envelopes wet on the march. This is written on some paper I confiscated. I managed to get enough I think, to do me until the war is over.

Your husband,

Samuel Patton

The donor of the July Artifact of the Month and the great-grand-nephew of Samuel Patton, Dr. William H. Race, and I recently noted that Bragg’s Tullahoma campaign coincided with the battles at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, leading to a true turning point in the war; however, unfortunately for Patton and the other soldiers, the war would still continue for nearly two more years.