This Month in North Carolina History

In the late summer of 1711, John Lawson, Surveyor-General of North Carolina, and Baron Christoph von Graffenried, a Swiss aristocrat, began what should have been a short, uneventful trip up the Neuse River. Lawson assured his companion that they would have no trouble with the Native Americans in the area, but by early September, the men were in the custody of a group of Tuscaroras and by the 16th, Lawson was dead.

Von Graffenried lived to tell the tale of their imprisonment, so much of what is known about Lawson’s death comes from his partner’s version of the event. Although initially the Native Americans merely questioned the two men about the purpose of their journey and had decided to set both of them free, they changed their minds when Lawson began quarreling with a Tuscarora chief. Von Graffenried managed to convince the Tuscaroras that Lawson did not speak for him and that he himself was under the protection of the Queen of England who would be sure to avenge his death. Von Graffenried was not present at the execution. Some versions of his account say that Lawson was burned to death, while others state that the Native Americans slit his throat. John Lawson may be considered the first casualty in what is known now as the Tuscarora War, a conflict that almost drove the Europeans from North Carolina and virtually destroyed the Tuscaroras.

In Lawson, the Native Americans lost one of their most sympathetic observers among the new settlers. During his journeys of exploration in South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, and possibly Pennsylvania, he studied not only the plants and animals of the new world, but also the cultures of its established peoples. Lawson attempted to be an objective chronicler of Native American customs, taking care to distinguish between the different nations. He collected American plants for a London botanist named James Petiver throughout his residence in the Carolinas, but Lawson’s own interests were much broader. He succeeded in combining those interests with the interests of Carolina’s owners, the Lords Proprietors, and soon after his arrival in Charlestown in late 1700, he was directed by the Proprietors to investigate the unsettled interior of Carolina. They later appointed him Surveyor-General of North Carolina and a member of the commission to determine the boundary between North Carolina and Virginia. These appointments gave him the opportunity to study the natural history of the area, meet with a number of different, and usually friendly, Native American nations, and acquire some valuable tracts of land for himself.

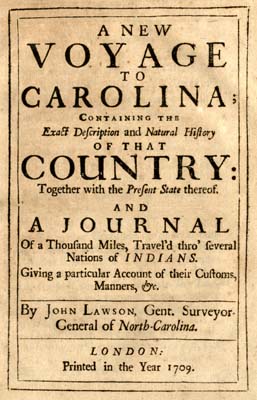

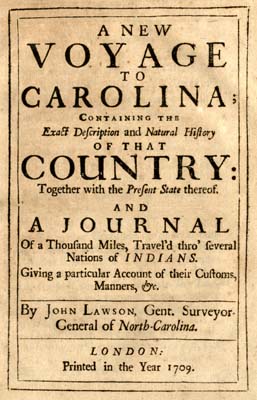

After about nine years in America, Lawson returned briefly to England, where as a result of his travels, he was able to publish a map of the Carolinas and one of the most influential early works on the natural history of America, A New Voyage to Carolina, in which he describes his journeys and findings. The book was published under a number of titles in the early eighteenth century in English and in German. It inspired many other explorers and naturalists, some of whom copied from it directly. Lawson was also concerned with promoting the settlement of North Carolina and was involved with the founding of both Bath and New Bern, the latter with Graffenried. He himself owned large tracts of land in the area of the two towns. While in London, he encouraged others, especially groups of European refugees living in England, to move to the colony. Despite his interest in and sympathy for the Native Americans, Lawson’s promotion of the growth of the colony was antithetical to their interests. His attempts to understand their culture did little to mitigate their perception that he was also destroying it.

Sources

Hudson, Marjorie. “Among the Tuscarora: The Strange and Mysterious Death of John Lawson, Gentleman, Explorer, and Writer.” North Carolina Literary Review, vol. 1 (Summer 1992), pp. 62-82.

Lawson, John. A New Voyage to Carolina. Ed. Hugh Lefler. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1967.

Lawson, John. A New Voyage to Carolina. London, 1709. Available online through Documenting the American South at http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/menu.html.

Saunders, William Lawrence, ed. The Colonial Records of North Carolina. Vol. 1. Raleigh, N.C.: P.M. Hale, 1890.