On May 7, 1915 off the coast of Ireland at 2:10 in the afternoon, on the final days of its trans-Atlantic journey to Liverpool, a torpedo fired by a German submarine slammed into the side of the RMS Lusitania. A mysterious second explosion ripped the passenger ship apart. In the chaos, many jumped into the water in an attempt to save themselves and were dragged down with the ship. Within 18 minutes the giant ocean liner slipped beneath the sea. One thousand one hundred ninety-eight of the 1,962 aboard died. The dead included 114 Americans.

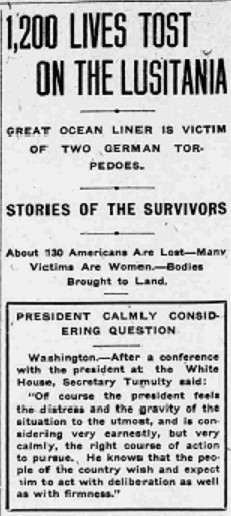

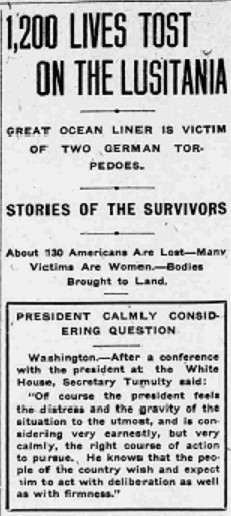

Stories about the catastrophe and tales of the survivors soon appeared in North Carolina newspapers, including The High Point Review on May 13, 1915.

One of the passengers aboard the Lusitania was a native North Carolinian with a well-known last name. Owen Hill Kenan was grandson of Owen Rand Kenan, Confederate congressman; great-grandson of Thomas Stephen Kenan, North Carolina senator and United States representative; and great-great-grandson of General James Kenan, a military leader during the American Revolutionary War and an early senator of the state of North Carolina. He was also cousin of William Rand Kenan Jr., a scientist, businessman and benefactor of the University of North Carolina. Owen and William were roommates at UNC in the 1890s.

Owen Kenan, a physician and seasoned traveler, was aboard the Lusitania on the first leg of his journey to Paris, where he planned to meet his niece, Louise Wise. The young woman was in boarding school and Kenan was due to escort her home to the U.S.

Kenan described the sinking in a letter to relatives, reprinted in the Wilmington Star on June 23, 1915. When the torpedoes struck the Lusitania, Kenan had just left his cabin and was heading to the Boat Deck. Once on deck, he wrote,

I saw third class passengers piling into life boats without order or command. As the boats which could not be or were not lowered filled up the bottoms pulled out and this mass of humanity was spilled 40 or 50 feet into the sea. I looked over the rail and saw nothing but hands and arms in the water below. The air was rent with their screams but there was nothing one could do. The boat was sinking and all this was transpiring most rapidly.

Kenan recounted that he returned to his cabin, put on his life jacket, and then headed outside to the deck.

After a few minutes I realized that the good ship was going and I went to the starboard and jumped into the sea, only to be carried down to a great depth by a terrible and strong suction. It was in this plight that I barely missed suffocation by drowning and being crushed to death by two life boats and debris deep under the surface. When the suction subsided I realized that I was caught under something. I had a feeling that my head was expanding and the thought flashed through my mind that perhaps I was losing consciousness.

I can’t tell why but I put my hands up over my head and, as if walking on the wall, pushed myself along until I felt the edge and pushed myself from under and began to come up. I kept my eyes open and when I began to see the light through the water I felt I should be saved though I was nearly done for and could feel myself swallowing great gulps of salt water. I came to the surface and gasped for breath. I looked up and I was directly under the forward smoke stack which was sticking out of the water at an acute angle and I said to myself that this would finish me. I went down again almost at once and my memory is blank.

When I opened my eyes again the entire boat had disappeared and the scene surrounding me of dead, drowning and struggling humanity mixed with a great quantity of broken debris I cannot describe. After four hours in the water I was taken aboard a torpedo boat destroyer almost frozen and much maimed.

Kenan was aboard the Lusitania with Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, a member of the wealthy American family, and Ronald Denyer, Vanderbilt’s valet. Kenan reported that after the torpedo strike he saw Vanderbilt leaning against a door and calling out, “They’ve got us now.” Several accounts suggest that Vanderbilt, who could not swim, handed off his life jacket to a young mother and helped numerous women and children into lifeboats. Neither he nor Denyer survived the sinking.

The torpedo boat destroyer that picked up Kenan and other survivors left them ashore at Queenstown (now known as Cobh), Ireland. Kenan remained in the town for several weeks as he recuperated from a severe case of tonsillitis. Reports suggest that Kenan had been suffering from the ailment prior to the sinking of the Lusitania and that his time in the water exacerbated his symptoms. Eventually, Kenan headed for Paris, met his niece, and the two returned to the U.S.

As the fighting in Europe continued, Kenan headed back to France and volunteered for the French army’s ambulance corps. For his service at Verdun, he received France’s Croix de Guerre. Kenan later joined the American Expeditionary Force’s medical corps and eventually was awarded the rank of colonel. Kenan’s time in Europe included medical relief in Turkey and Russia during the Revolution. Upon returning to the U.S. in the early 1920s, Kenan devoted his time to providing medical care for Kenan family members and wealthy friends and collecting art. In 1931, he donated one of his art purchases, a wooden statue of Sir Walter Raleigh, to the UNC Library. The statue is on view in the North Carolina Collection Gallery.

During his life, Kenan maintained homes in Palm Beach, New York, Wilmington and Paris. He died at age 91 in 1963.

Among the items to survive Kenan’s near-drowning on the Lusitania was his pocket watch. Its hands are frozen at 2:33, a short time after the initial torpedo strike. The watch is now in the collection at Liberty Hall, a Kenan family home in Duplin County.

Owen Kenan’s life and art collection was celebrated in “A Wilmingtonian Abroad, The Remarkable Life of Colonel Owen Hill Kenan,”, an exhibition mounted at the St. John’s Museum of Art (now the Cameron Art Museum) in Wilmington in 1998-1999.