Seen on the sea, no sign; no sign, no sign

In the black firs and terraces of hills

Ragged in mist. The cone narrows, snow

Glares from the bleak walls of a crater. No.

Again the houses jerk like paper, turn,

And the surf streams by: a port of toys

Is starred with its fires and faces; but no sign.

In the level light, over the fiery shores,

The plane circles stubbornly: the eyes distending

With hatred and misery and longing, stare

Over the blackening ocean for a corpse.

The fires are guttering; the dials fall,

A long dry shudder climbs along his spine,

His fingers tremble; but his hard unchanging stare

Moves unacceptingly: I have a friend.

The fires are grey; no star, no sign

Winks from the breathing darkness of the carrier

Where the pilot circles for his wingman; where,

Gliding above the cities’ shells, a stubborn eye

Among the embers of the nations, achingly

Tracing the circles of that worn, unchanging No—

The lives’ long war, lost war—the pilot sleeps.

-“The Dead Wingman” from Randall Jarrell’s Losses, published in 1948.

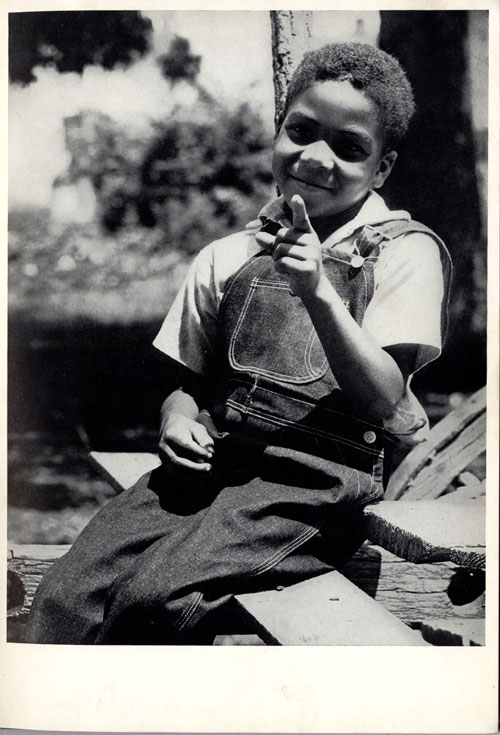

On Pearl Harbor Day we remember the life and work of Jarrell, whose poetry was deeply influenced by World War II and his service in the U.S. Army Air Service. Although Jarrell aspired to be a pilot, he spent 1942-1946 as a celestial navigation tower operator, primarily in Arizona. The stories he heard from pilots and others inspired numerous poems, including his best-known, “The Death of the Ball-Turret Gunner,” published in his second volume of verse, Little Friend, Little Friend, in 1945.

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

Upon leaving the Air Service, Jarrell, who had already received acclaim for his poetry, moved to New York City. He continued writing verse, thanks to a Guggenheim Fellowship, served as the book review editor for The Nation and taught at Sarah Lawrence College.

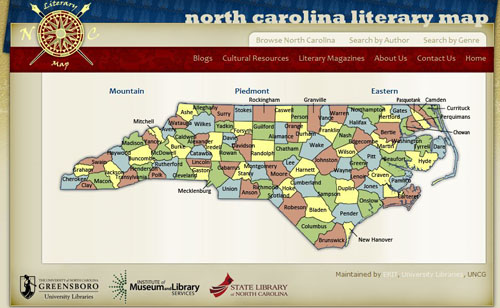

In 1947, Jarrell, who had quickly tired of New York, moved to Greensboro, where he taught in the English department at Women’s College (now UNC-Greensboro). With the exception of short teaching stints around the country and internationally, Jarrell remained at Women’s College for the next 18 years. He served as the nation’s Poet Laureate from 1956-1958. In 1961 he was awarded a National Book Award for his poetry volume The Woman at the Washington Zoo. And in 1962 Jarrell received the O. Max Gardner Award, one of the state’s highest honors.

Jarrell died on October 14, 1965, when he was struck by a car while walking at dusk along U.S. 15-501 near Chapel Hill. He had moved there to teach at the university a few months prior. In addition to poetry, Jarrell’s published works include children’s stories, essays, criticism and a single novel.