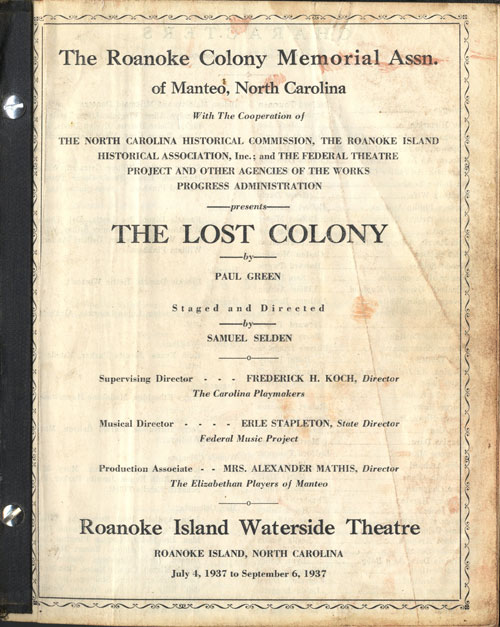

Happy Birthday Thomas Wolfe! The novelist was born in Asheville on this day in 1900. Though he left his native state after graduating from the University of North Carolina in 1920, his work was forever rooted in North Carolina and he remains one of our state’s most celebrated authors.

Wolfe was a proud alumnus of UNC and wrote fondly of his time there in a letter to his classmate Benjamin Cone. The letter was written in July 1929, just before the publication of Wolfe’s first novel, Look Homeward, Angel. In an often-quoted passage, Wolfe writes,

“And after all, Ben, back in the days when you and I were beardless striplings — ‘forty or fifty years ago,’ as Eddie Greenlaw used to say — the Hill was (praise God!) ‘a small southern college.’ I think we had almost 1000 students our Freshman year, and were beginning to groan about our size. So far from forgetting the blessed place, I think my picture of it grows clearer every year: it was as close to magic as I’ve ever been, and now I’m afraid to go back and see how it is changed. I haven’t been back since our class graduated. Great God! how time has flown, but I am going back within a year (if they’ll let me).”

It’s a great letter, worth reading in its entirety on the North Carolina Collection website. One of my favorite parts is where Wolfe acknowledges that even after substantial editing his is going to be a very long book and that he hopes Cone will “manage to stick it to the end.”

In closing, Wolfe writes again of his fond memories of the University and his classmates, though with a touch of apprehension as he understands the potential for misunderstanding that lay ahead when so many people from Asheville and Chapel Hill would find thinly-disguised versions of themselves in the novel.

“But this is perhaps the longest letter I shall write to anyone concerning my book, and I do it for this reason: you stand as a symbol of that happy and wonderful life I knew during 1916-1920 (don’t think from this that my present life is wretched — on the contrary, now that I am really beginning to do the work I love, it is fuller and richer than it’s ever been) But I shall never forget the great days at Chapel Hill, and my friends there. Such a time will come no more. I have kept silence for years. I have lived apart from most of those friends, probably most of them have forgotten me. But I think you will believe me when I tell you most earnestly that I value the respect and friendship of some of those people as much as I value anything — with two exceptions, one of which is my work. So, no matter what you think of my book, continue to remember the person who wrote it as you always have.”