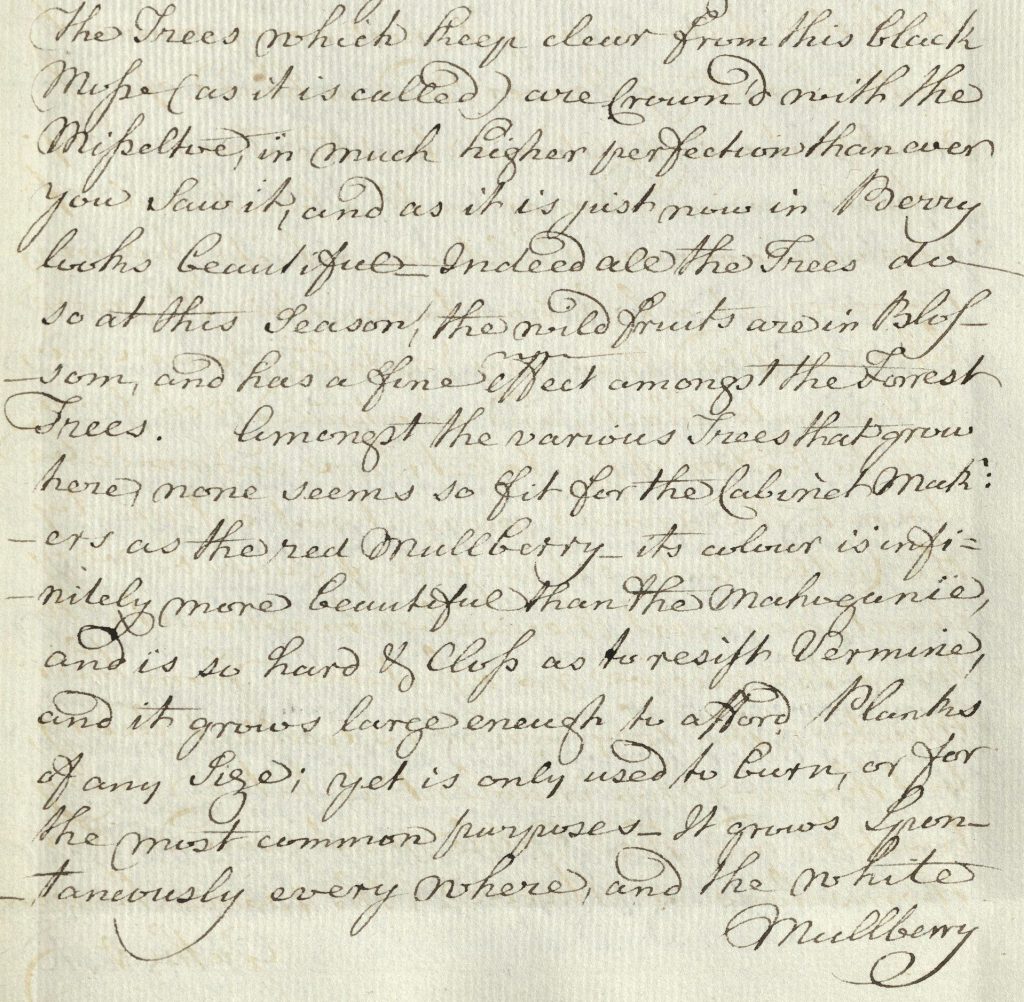

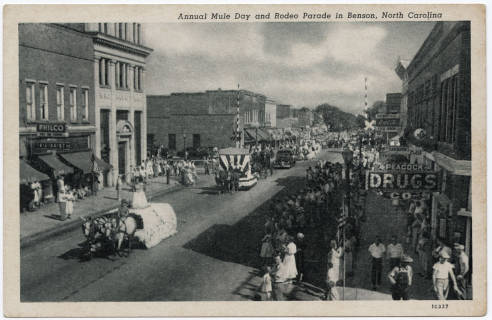

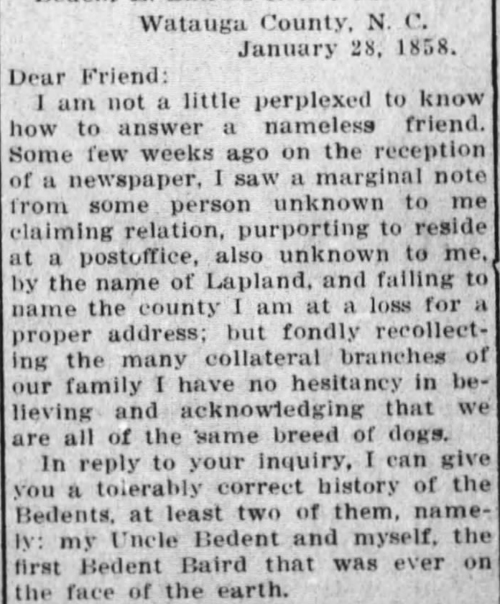

In 1912, the Asheville Gazette-News reprinted a letter (A portion of which is above. Click on the image to sell the full letter), originally from 1858, from Bedent Baird of Watauga County to Zebulon Baird Vance, who at the time was a very young Congressman. Bedent Baird describes what he knows about his family lineage and wonders if his Watauga County Baird clan was in any way related to the Buncombe County one represented by Vance. The paper itself adds a little bit about the family’s history for context. Unfortunately, the matter could not have been settled with this information, because the family tree described in the article is wrong.

To make a somewhat complicated story (filled with many Zebulons and Bedents) short: the two Baird clans in Western North Carolina are indeed related. Their common ancestor was John Baird, born in 1665 in Scotland. He came over in 1683 and settled in New Jersey. He and his wife, Mary Bedent, had five sons: Andrew, John Jr., David, William, and Zebulon.

The Watauga County Bairds are descended from Andrew. Andrew’s son Ezekiel was the first of that line to end up in North Carolina. They have been quite prominent in the community, particularly for being some of the earliest settlers in Valle Crucis. Bedent Baird, author of the 1858 letter, was also a magistrate and politician, representing the part of Watauga that used to be Ashe County.

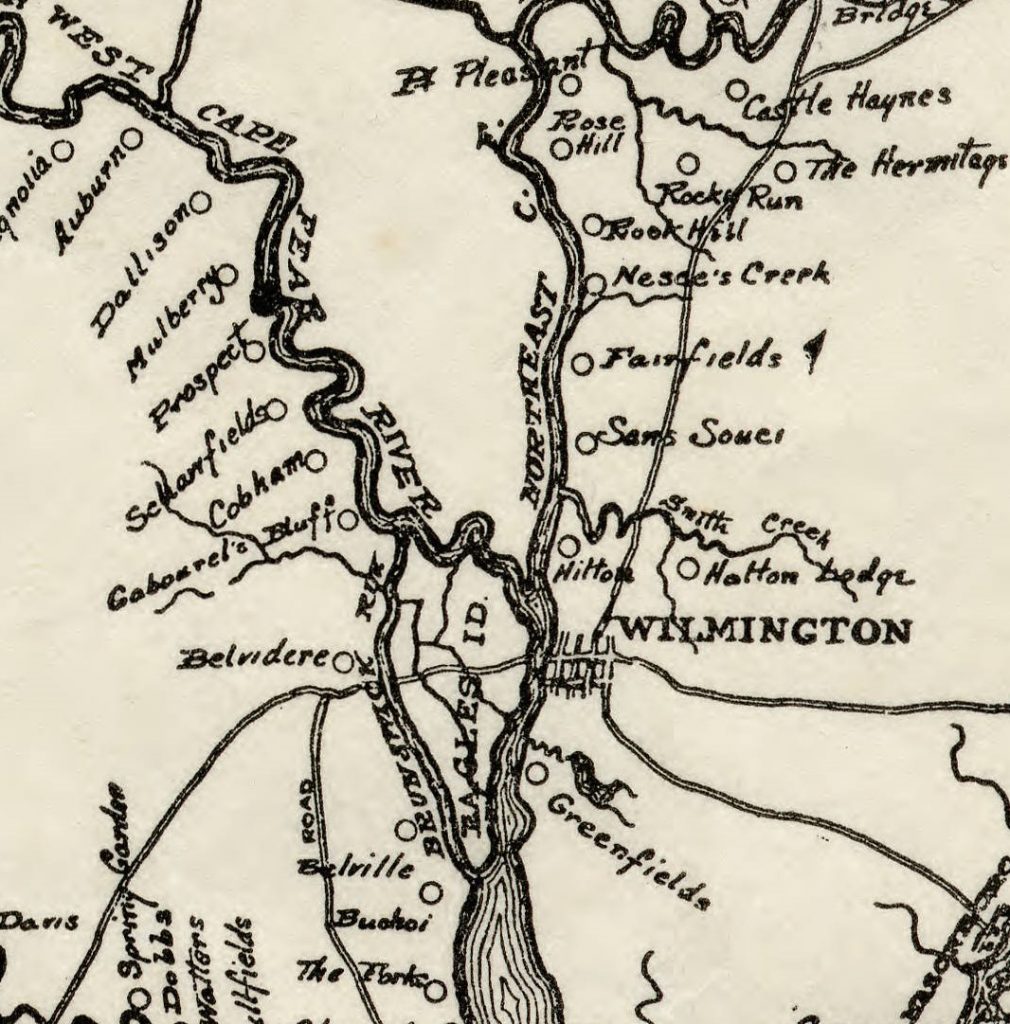

The Buncombe County Bairds are descended from John Junior. John Junior’s grandsons Bedent and Zebulon were some of the earliest settlers in Buncombe County, about 1793. The brothers had the first grist mill in the county and they played significant roles in the early days of what is now the City of Asheville. They bought a large amount of land, with Bedent settling on Beaver Dam and Zebulon near the French Broad. Zeb rose to some political prominence, serving as Senator for multiple terms. They also forged a friendship with David Lowry Swain, who helped manage Zeb’s affairs after he died in 1824. Swain also helped his deceased friend Zebulon’s grandson, Zebulon Baird Vance, attend UNC-Chapel Hill.

There are couple things that the article and letter in the Asheville Gazette-News get wrong, therefore muddying the process of answering the question about a common ancestor. The most confusing is in the listing of John Baird’s children. In doing so, they completely skip a generation. Bedent, Samuel, Obadiah, Borzilla, Jonathan, Ezekiel, etc. were the children of John Baird’s son Andrew, and therefore grandchildren of the patriarch. Bedent himself completely forgets to mention his own grandfather, Andrew, the actual son of John and Mary Baird, which is a bit of a glaring omission. The letter also claims that his uncle was the “first Bedent.” As is probably clear, the two Baird families in North Carolina did not seem to know much about each other, and therefore Bedent Baird didn’t know about his own cousin Bedent, son of William, over Asheville-way.

It is unclear if this relationship between the clans was resolved, at least not in the public’s imagination. The article is certainly curious for how much it got wrong. And for featuring a letter over 50 years old that quite possibly never made it into the hands of Zeb Vance. Most importantly, though, it shows the affection and curiosity the readership and citizens had for Vance and for the Bairds. Indeed, the significant roles that both families played in the history of Western North Carolina make them a fascinating study, and not just due to the predilection for naming children Bedent and Zebulon.

For further reading:

Arthur, J. P. (2002). A history of Watauga County, North Carolina : with sketches of prominent families. Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Pub. Co.

Arthur, J. P. (1973). Western North Carolina; a history, 1730-1913. Reprint Co.

Biddix, C. D. (1981). The Heritage of old Buncombe County. Asheville, N.C.: Hunter Pub. Co.

Blackmun, O. (1977). Western North Carolina, its mountains and its people to 1880. Boone, N.C.: Appalachian Consortium Press.

Dowd, C. (1897). Life of Zebulon B. Vance. Charlotte, N.C.: Observer Print. and Pub. House.

Edwards and Broughton Company (Raleigh, N.C.). (1890). Western North Carolina : historical and biographical. Charlotte, N.C.: A.D. Smith & Co.

Gaffney, S. R. (1984). The heritage of Watauga County, North Carolina. Winston-Salem, N.C.: Heritage of Watauga County Book Committee in cooperation with the History Division of Hunter Pub. Co.

McKinney, G. B. (2004). Zeb Vance : North Carolina’s Civil War governor and Gilded Age political leader. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Sondley, F. (1977). A history of Buncombe County, North Carolina. Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Co.

Image:

Episode and Interlude. (February 20, 1912). Asheville Gazette-News. p. 4.