This Month in North Carolina History

Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina, is the final resting place for Thomas Wolfe, Asheville native and North Carolina’s most famous author. It is perhaps less well known that Riverside also contains the grave of William Sydney Porter who, under the pen name O. Henry, had gained a national and even an international reputation as a writer at the turn of the twentieth century.

Porter was born in Greensboro, North Carolina, on September 11, 1862. He was educated by his aunt, Evelina Porter, until he was fifteen, when he left school to go to work in the drugstore of his uncle. He became a licensed pharmacist at nineteen. In 1882 Porter left Greensboro for Texas hoping to improve his health. For almost a decade he worked at a number of jobs, including ranch hand, cook, draftsman, and, ultimately, bank teller. At the same time he began to write short pieces for local newspapers and develop his talent as a cartoonist. In 1895 Porter left his position at the First National Bank of Austin to become a columnist and reporter for the Houston Daily Post. He married Athol Estes in 1887. The couple had a son, who died in infancy, and a daughter, Margaret Worth Porter.

Porter’s life changed dramatically in 1896 when he was indicted for fraud in connection with his work with the bank in Austin. Porter protested his innocence, but, to avoid standing trial, he fled to Central America. Learning that his wife was suffering from an incurable disease, Porter returned to Austin in 1897. After his wife’s death, he was tried, convicted, and sentenced to five years in the Ohio Penitentiary. After serving a little over three years he was released for good behavior in 1901. Working as a druggist in the prison hospital gave Porter the time to continue his writing. His first short story was published in 1898 and others followed. To conceal his identity and imprisonment from his publishers, Porter wrote under several pseudonyms, but the one on which he finally settled was O. Henry. On his release from prison Porter moved with his daughter to New York City, where for the remaining eight years of his life he wrote prodigiously, producing more than 380 short stories, sometimes at the rate of one a week.

O. Henry became one of America’s most popular writers, with an international following as well. Whether his theme was serious or comic, his writing style was casual, light, and playful. He created hundreds of characters from the people he found around him in the west or in New York. Clerks, waitresses, ranch hands, policemen, confidence men – The Four Million, as he entitled one of his collections of stories – were his inspiration. O. Henry was most famous for his surprise endings. In “The Cop and the Anthem” a New York hobo, Soapy, tries repeatedly to get himself arrested so he can spend the cold winter months in the relative warmth of the city jail on Riker’s Island. Discouraged because all of his efforts have failed spectacularly and comically, Soapy sits on a bench and listens to a beautiful anthem being sung in a nearby church. Under the influence of the music Soapy pledges to become a new person and rebuild his life. At that moment a patrolman arrests him for loitering and marches him off to The Island.

Porter’s health began to fail in 1908 under the impact of diabetes and heavy drinking. He traveled to Asheville in an attempt to recuperate and believed he had regained much of his strength while he was there. He returned to New York to resume work, but his health continued to deteriorate. He died on June 5, 1910.

Sources:

O’Connor, Richard. O. Henry: the legendary life of William S. Porter. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1970.

Edgar E. Macdonald, “Porter, William Sydney.” In Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, vol. 5. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Image Source:

Porter, William Sydney (O. Henry) in the Portrait Collection, #P002, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

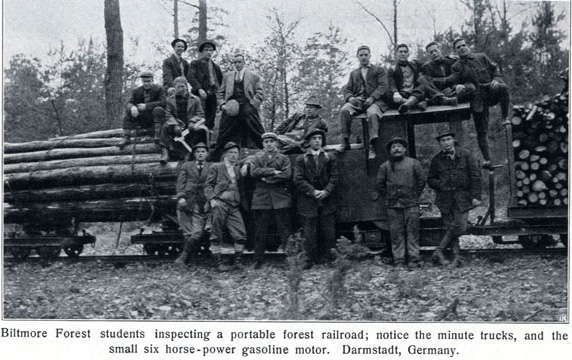

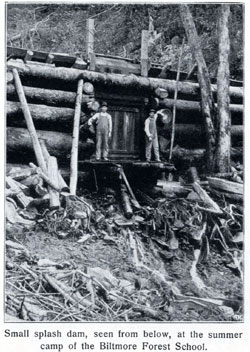

ains of western North Carolina produced Biltmore, the magnificent mansion near Asheville that has become one of the best known tourist attractions in North Carolina. Vanderbilt also planned an estate worthy of the house, ultimately buying more than 120,000 acres of mountain land. He had hired one of the country’s premier landscape architects to lay out the lands and gardens surrounding Biltmore, and, in the same spirit, Vanderbilt wanted his vast forest lands managed by a skilled, professional forester. At the time there were only two trained foresters in the United States, Gifford Pinchot and Bernard Eduard Fernow. Pinchot had prepared preliminary plans for the Biltmore forests but would not take on the permanent job of caring for them. On the recommendation of Pinchot and others, Vanderbilt sought his forester in Europe, offering the position to Carl Alwin Schenck, a native of Darmstadt, Germany, who studied forestry at the Universities of Tubingen and Gissen, receiving his Ph. D. in 1894.

ains of western North Carolina produced Biltmore, the magnificent mansion near Asheville that has become one of the best known tourist attractions in North Carolina. Vanderbilt also planned an estate worthy of the house, ultimately buying more than 120,000 acres of mountain land. He had hired one of the country’s premier landscape architects to lay out the lands and gardens surrounding Biltmore, and, in the same spirit, Vanderbilt wanted his vast forest lands managed by a skilled, professional forester. At the time there were only two trained foresters in the United States, Gifford Pinchot and Bernard Eduard Fernow. Pinchot had prepared preliminary plans for the Biltmore forests but would not take on the permanent job of caring for them. On the recommendation of Pinchot and others, Vanderbilt sought his forester in Europe, offering the position to Carl Alwin Schenck, a native of Darmstadt, Germany, who studied forestry at the Universities of Tubingen and Gissen, receiving his Ph. D. in 1894.