“Thomas Kunkel’s biography adds some telling details to what [Joseph] Mitchell’s readers already know about his childhood as the eldest son of a prosperous cotton and tobacco grower in North Carolina. Perhaps the most striking of these is Mitchell’s trouble with arithmetic—he couldn’t add, subtract, or multiply to save his soul—to which handicap we may owe the fact that he became a writer rather than a farmer. As Mitchell recalled late in life:

You know you have to be extremely good at arithmetic. You have to be able to figure, as my father said, to deal with cotton futures, and to buy cotton. You’re in competition with a group of men who will cut your throat at any moment, if they can see the value of a bale of cotton closer than you. I couldn’t do it, so I had to leave.

“Mitchell studied at the University of North Carolina [1925-29] without graduating and came to New York in 1929, at the age of twenty-one….”

— From “The Master Writer of the City” by Janet Malcolm in the New York Review of Books (April 23)

But the reddest meat in Kunkel’s “Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker” is the revelation of how much fiction Mitchell infused into such classic works as “Joe Gould’s Secret” and “Up in the Old Hotel.” (“Does It Matter?” some ask.)

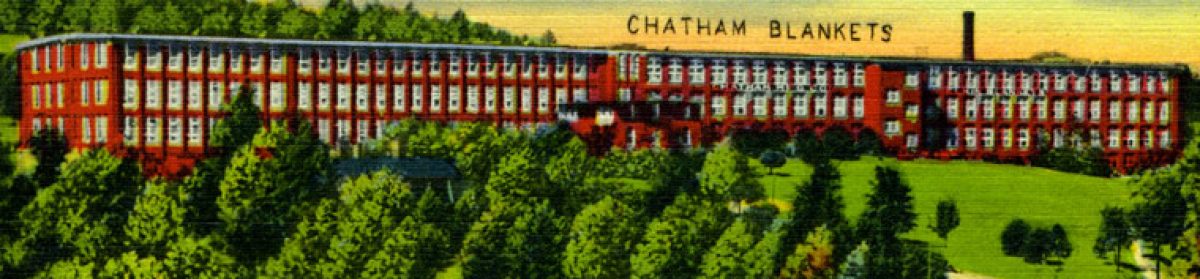

Earlier: Kunkel on Mitchell’s Fairmont roots.