“The price African American owners of property along bodies of water (or places that would become bodies of water) paid for the South’s ‘progress’ in the decades following the death of Jim Crow was, quite often, their land….

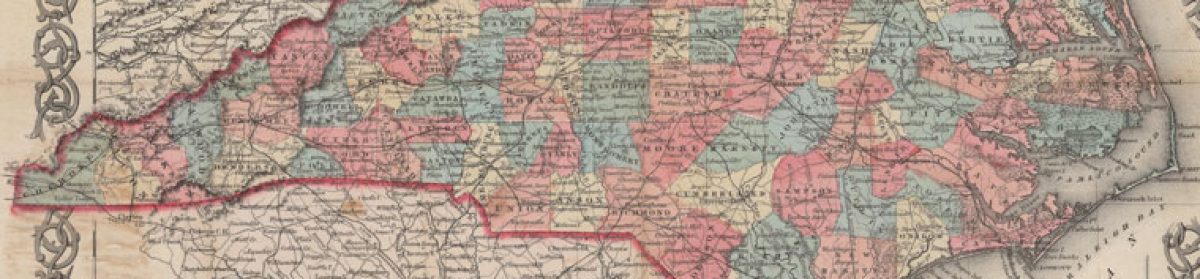

“The U.S. Corps of Engineers began drawing up plans for the creation of Jordan Lake, which would control flooding and provide the water necessary to accommodate the region’s projected population growth — along with expensive, waterfront property to house its most affluent migrants — and catapult the poor, rural county from the tobacco belt into the Sunbelt.

“‘I’ll never forget,’ [Edna] Cole recalls, ‘a man came to my dad’s with a briefcase and telling him that Jordan Lake was going to come and part of the land in Chatham County was going to be used as a flood area and some of it was going to be for wildlife…. And he took the briefcase out and showed him some of the things that was going to happen and told my father that, you know, if he didn’t sell it, they would take it anyway.’ Seeing little option, Edna advised her elderly father to sell the man 22.5 acres of their farmland for $5,000. Jordan Lake was completed in 1982.

” ‘In later years we found out that this man was not from the Corps at all, but he had inside information about what the progress was or when it was going to happen.’ Through examining courthouse records, Cole learned that [he] later sold the Coles’ farm to the Corps for twice the amount he paid.”

— From “The Land Was Ours: African American Beaches from Jim Crow to the Sunbelt South” by Andrew W. Kahrl (2012)