Today marks the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, the battle in which Napoleon was at last decisively defeated. Now remembered primarily as a conflict between England and France, the Battle of Waterloo took place south of Brussels in present-day Belgium and included armies from Prussia, Austria, Hanover, Nassau, the Duchy of Brunswick, and England. This Seventh Coalition formed expressly to defeat Napoleon after his return to power during the Hundred Days following his exile on Elba. The Battle of Waterloo ended Napoleon’s rule and two decades of war across the continent of Europe. A precursor to the World Wars of the twentieth century, the Napoleonic Wars brought issues of imperialism and nationalism to the fore, inaugurating modern warfare as they changed the face of Europe.

The Battle of Waterloo is also significant in its immediate incorporation into popular imagination. Only days after news of the victory reached British soil, the battle was already being heralded as one of the most important events in history. Commemoration of the battle began within weeks, bolstered by eye-witness accounts from returning soldiers–many more of whom were literate than had ever been the case in previous wars.

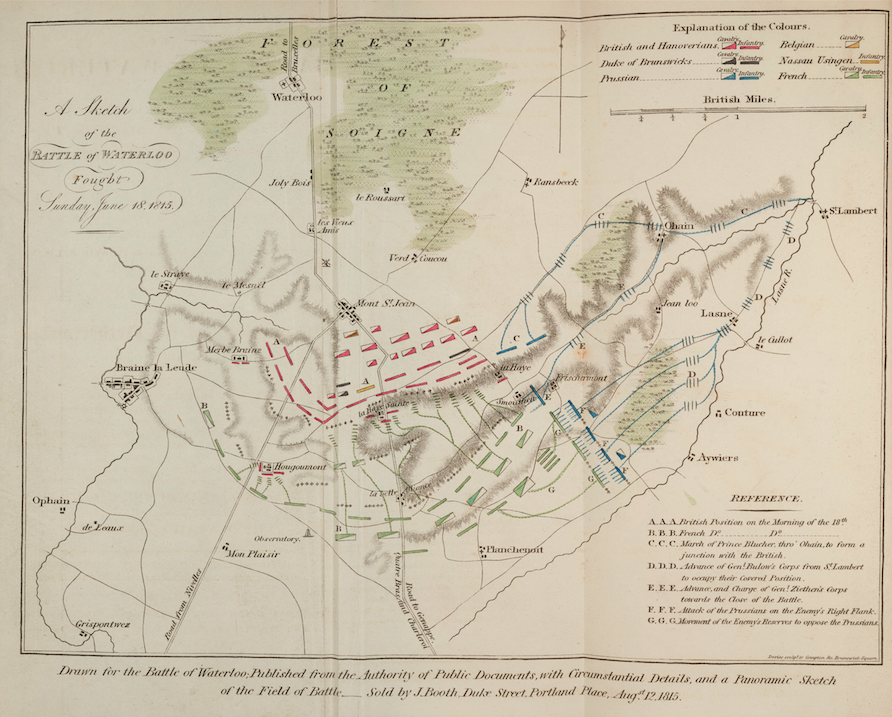

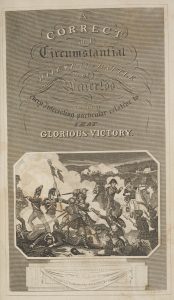

Accounts of the battle took advantage of modern media. Portraits of the generals and principle agents of the battle appeared frequently, creating a cult of celebrity around the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon in particular. Maps, memorials, charts, and dramatic scenes all sought to deliver to the British reader an authentic experience of the battle and its particulars.

Literary reactions to the battle also abounded. Newspapers and journals of the day printed patriotic poetry affirming Britain’s supremacy in the wake of the victory. Leading writers, regardless of their political affiliations, joined the chorus. Sir Walter Scott was among the first to try his hand. His highly publicized Field of Waterloo figured itself as a philanthropic gesture; the proceeds were to fund relief efforts for returning soldiers.

William Wordsworth, long troubled by the threat to European culture and history represented by the chaotic ruin of Napoleon’s campaign, published an ambitious Pindaric ode titled Thanksgiving Ode, January 18, 1916 to commemorate the battle–an effort that met with mixed reviews due to his reluctance to praise the Duke of Wellington, whom he was known to dislike.

Robert Southey’s contribution, The Poet’s Pilgrimage to Waterloo, participated in the emerging tourist culture that surrounded Waterloo and other sites of the wars. Southey’s visitation to the scene of the battle provides a template for the literary traveller, who can follow in the poet’s footsteps on a pilgrimage of his own. That Southey’s poem was used as a kind of guide book is apparent in the Rare Book Collection’s copy, which is bound together with an actual travel guide to Belgium, published in the same year.

The primacy of the battle did not fade as the nineteenth century wore on. It remained a watershed moment in the British cultural consciousness. Eye-witness accounts of the battle continued to emerge throughout mid-century, including Fanny Burney’s posthumously published narrative in her Diary and Letters of Madame d’Arblay (1842) and Robert Gleig’s popular Story of the Battle of Waterloo (1848). William Makepeace Thackeray’s fictionalized version of the battle provided emotional crisis for the heroine of his much-read novel Vanity Fair (1847).

Models and panoramas of the battle provided another avenue for commemoration. Panorama paintings first began to appear in the 1780s but gained wide popularity during the nineteenth century as a pre-cinematic immersive experience for those who could not afford to travel to historic sites. Guides, prints, pamphlets, and other ephemeral publications produced in conjunction with panorama displays can help us recreate the space of the panorama, if not the experience.

Patrons interested in learning more about the history of Waterloo may consult the Rare Book Collection’s Hoyt Collection of French History. The collection includes over 5,000 valuable books and documents related to the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars.