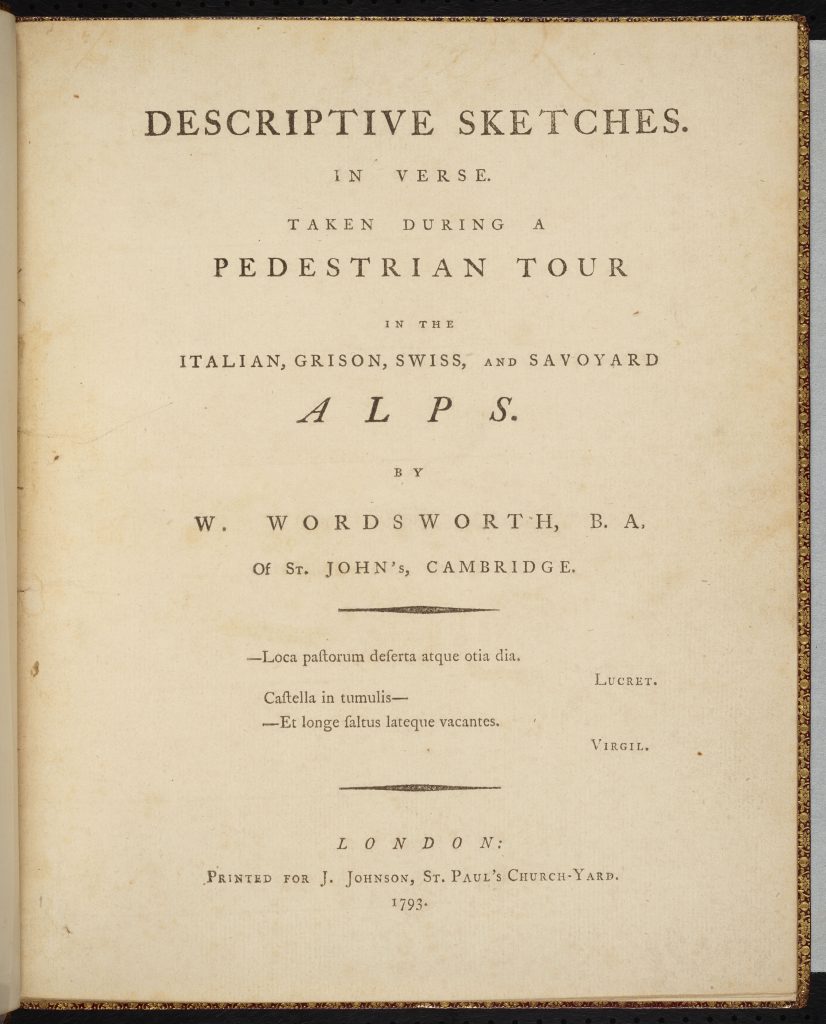

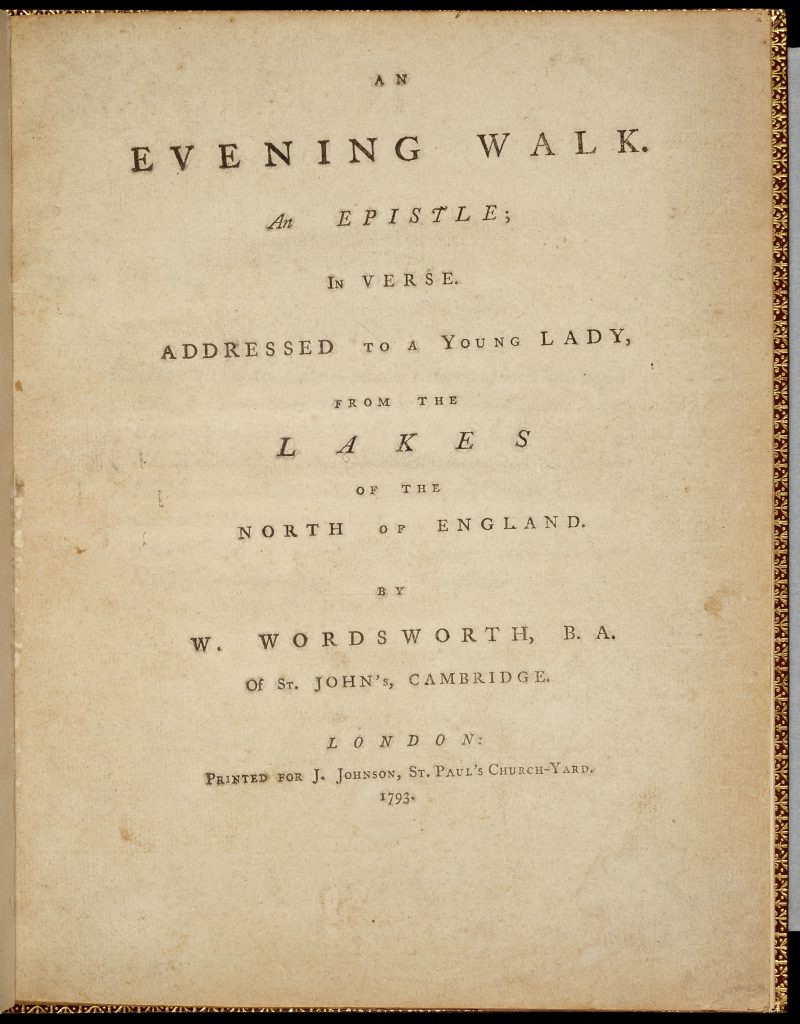

One of the most difficult tasks in mounting exhibitions is the sometimes nerve-wracking choice of what to include and what to edit out. “Kill your darlings,” as Faulkner would have it in writing fiction, is just as apt when choosing which six or seven books and objects will stand in as evidence of a rich and complicated historical narrative. These decisions were particularly difficult for Lyric Impressions: Wordsworth in the Long Nineteenth Century—the rare book exhibition that opened at Wilson Library on January 20th. Clocking in at more than 2,000 volumes, The William Wordsworth Collection is so vast that one exhibition could never do justice to the whole. To remedy that reality, we’ll be undertaking a series of blog posts to explore Wordsworth publications that didn’t make it past the cutting room floor. Each post will expand on the major themes of the exhibition. In this post, we’ll explore Wordsworth’s productive and turbulent development in the decade of the 1790s by considering his first published books: An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches (1793).

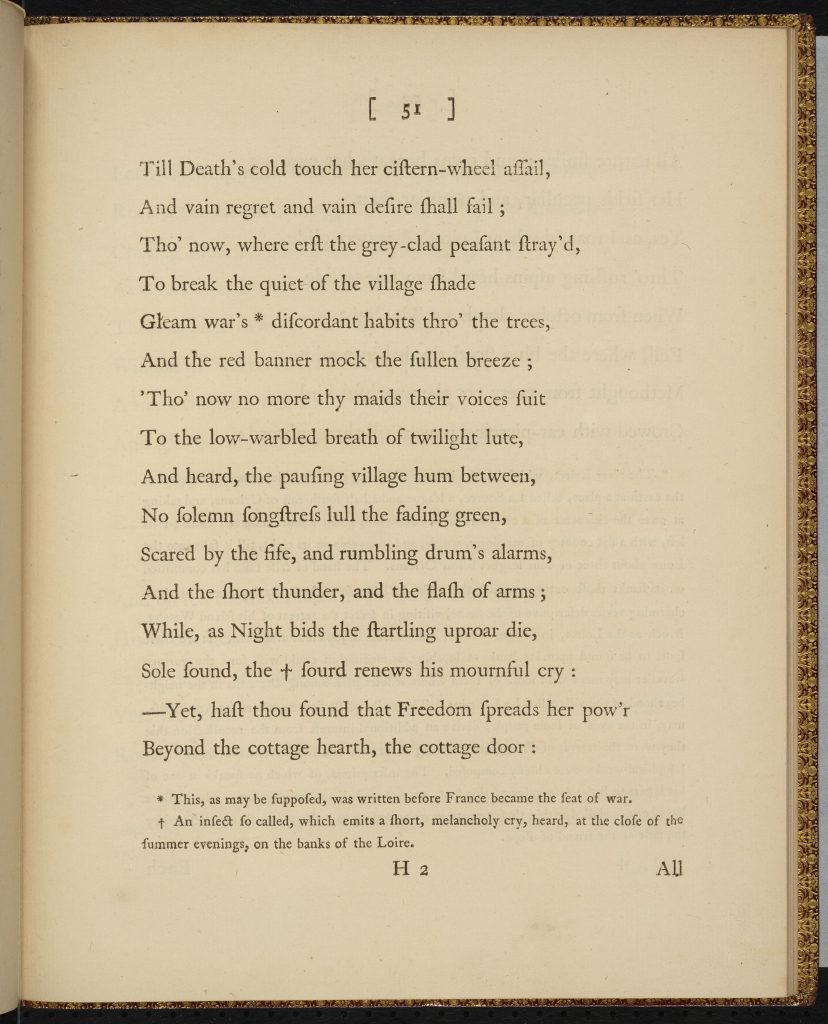

By the time he published Lyrical Ballads in 1798, Wordsworth had developed a distinctive poetic voice, one he conceived of as a departure from the studied, high-flown style popular for much of the eighteenth century. In An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches, composed between 1787 and 1792, this poetic voice was still nascent; in both poems, Wordsworth relies on earlier poetic models, such as Thomson’s The Seasons (1730) and Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). The poems’ allusive qualities were not lost on his contemporary audience, whose mixed critical reception of the works drew attention to their derivative qualities. Neither were they lost on Wordsworth himself, who later wrote that he found them to be “juvenile productions, inflated and obscure,” nevertheless, they contained “many new images and vigorous lines….”

Sales of An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches were not robust. While it is unknown how many copies were issued in the initial print run, the audience of the two works appears to have been small. Wordsworth commented in 1801 that “Johnson [his publisher] has told some of my Friends who have called for them, that they were out of print: this must be a mistake. Unless he has sent them to the Trunk-maker’s they must be lying in some corner of his Warehouse, for I have reason to believe that they never sold much.” Whether or not the unsold copies were indeed scrapped for paper waste, today copies of the first editions are relatively scarce.

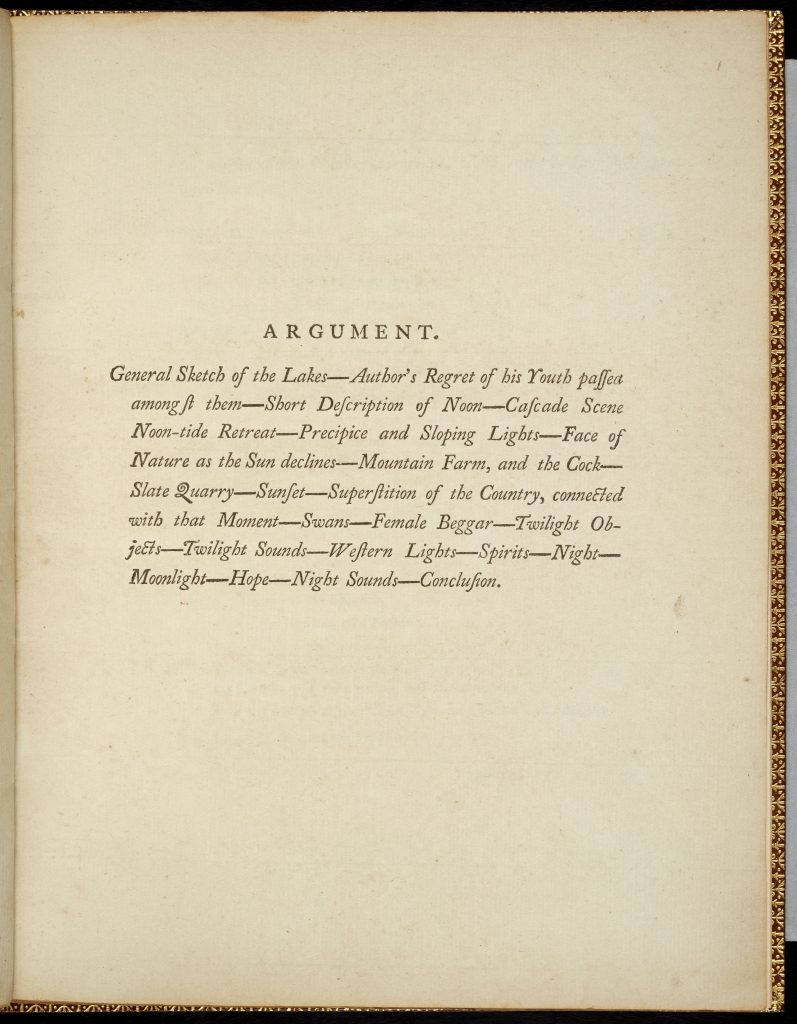

Aside from offering a window on Wordsworth’s developing poetic voice, An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches are important works juxtaposed with Wordsworth’s politically charged poetry of the same period. In the 1780s and 90s, Wordsworth was also composing more explicitly radical poems, such as “Salisbury Plain,” and “Letter to the Bishop Llandaff.” An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches both follow a tradition of loco-descriptive verse, where the poet’s reaction to an evocative landscape or monument triggers a philosophic and aesthetic experience. They do not, as some of his other poems of the 1790s do, explicitly confront the incendiary political issues of his youth. Though Wordsworth’s political attitudes are not wholly absent from his published verse, his unpublished (or largely unpublished) poetry is more direct and, at times, inflammatory.

Wordsworth’s radical discontent in the 1790s reflected the mood of the country. At the beginning of the decade, economic disparity had reached alarming levels. Radical sentiment, spurred by the rhetoric of the American Revolution and the ideals of the French Revolution, circulated widely. But 1793 would prove to be a decisive turning point, as the British Government enacted a series of increasingly draconian measures designed to stamp out radical dissent, among them the Treason Trials and the suspension of habeas corpus in 1794 and the so-called “Gagging Acts”—the Treason Act and Seditious Meetings Act—in 1795. The government actively sought out radical agitators and their associates—including Wordsworth and Coleridge, who were purportedly investigated by a government spy in 1796.

An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches anticipate Wordsworth’s poetic trajectory toward philosophic verse and also the turning political tide in England. By the close of the 1790s, Wordsworth’s idealistic radicalism had matured and changed, though he would maintain an active interest in political and current events throughout his life.