The history of Western anatomy extends from ancient times to the modern analyses of bodily function; however, the scientific study of anatomy, particularly of the human body, is a recent historical phenomenon dating only so far back as the 2nd century. During this time, the physician Galen compiled most of the writings from other ancient authorities and used empirical observation to develop theories of organ function. He supplemented authoritative knowledge from classical sources by performing vivisections, mostly on animals, and applying those observations to human anatomy. His work as a gladiatorial physician afforded him additional opportunities to study various wounds without the need to preserve and examine corpses, and these observations helped him expand his theories on organ function, the humors, and disease. His tracts became the authoritative foundation for physicians for the next 1300 years.

Contrary to a popular misconception, the dismemberment of corpses wasn’t officially restricted during the Middle Ages and Renaissance; nevertheless, human dissection was rare in part because of local persecution and in part because physicians acquired their anatomical training from book-learning rather than practical observation. But by the 14th century, some European universities began holding anatomical lectures. Within 300 years, dissections became increasingly more common, and the modern field of anatomy as we know it today came into being.

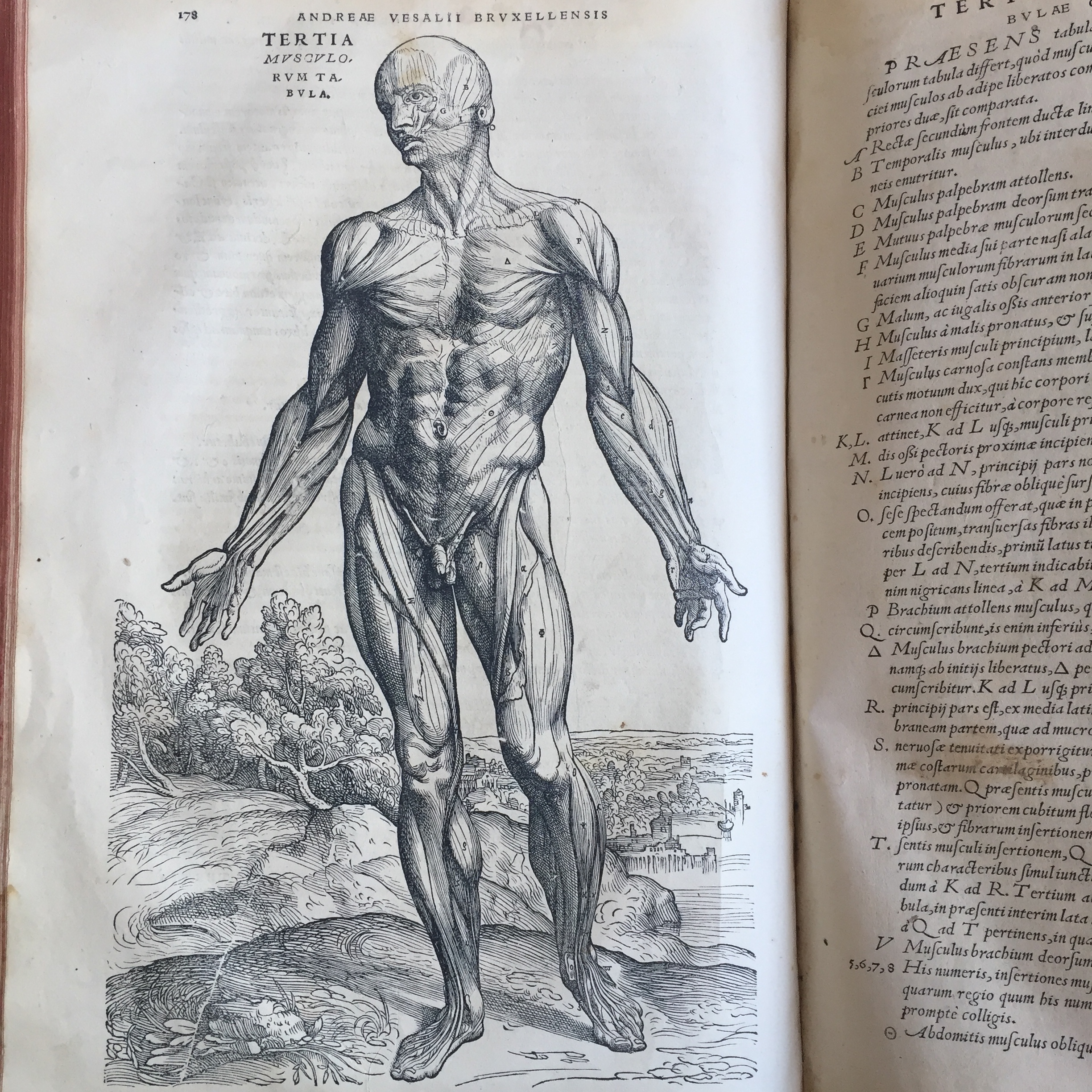

With the advent of the printing press, print materials like books and pamphlets provided the means of recording and sharing the observations found in systemic dissections at major European universities. Anatomists like Andreas Vesalius began to question relying solely on authoritative sources to draw anatomical and medical conclusions. Vesalius openly denied Galen’s anatomical teachings and advanced the opinion that a new account of human anatomy was necessary. By the end of the 1540s, his De humani corporis fabrica revolutionized anatomical study; however this work, though attractive, was not anatomically correct, and it required refinement from future anatomists.

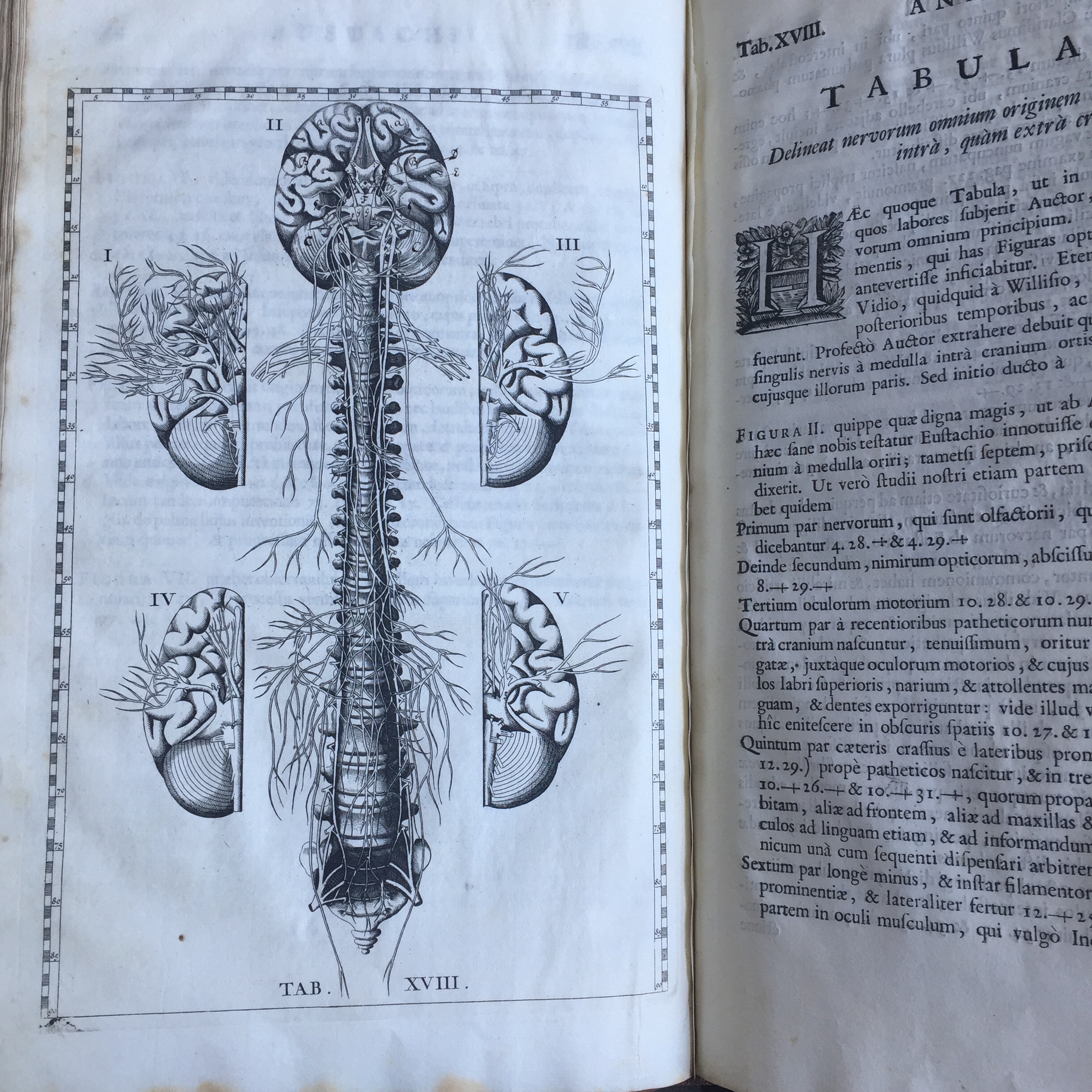

Bartolomeo Eustachi, unlike Vesalius, was a noted supporter of Galen. In addition to his rediscovery and accurate description of the tube that now bears his name in the internal ear, Eustachi was the first anatomist to accurately study the teeth and to describe the first and second dentition. He also discovered the adrenal glands. However, it took many years for him to complete his intricate set of anatomical engravings. By the time he finished them in 1552, Vesalius was already published. Eustachi would never see his own book printed in his lifetime.

Eustachi’s student, Juan Valverde de Amusco, had an equally fraught relationship with Vesalius. Valverde’s best-known work, Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano, was published in Rome in 1556, 13 years after Vesalius. Like Vesalius, Valverde criticized Galen, but he disagreed with several of Vesalius’s conclusions. Moreover, he blamed Vesalius and other Italian anatomists for failing to mitigate Spanish anatomists’ ignorance. In his Historia, Valverde asserts that the goal of the book is to aid Spanish surgeons whose minimal knowledge of Latin kept them unaware of the major anatomical reforms coming out of Italy in the mid-sixteenth century.

All but four of the 42 plates in Valverde’s book actually come directly from Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica. This infuriated Vesalius, who bitterly accused Valverde of plagiarizing him and performing few if any dissections himself. The inclusion of the plates also led many non-Spainards to believe Valverde had merely translated Vesalius’s work into Spanish. However, Valverde refuted these claims. In the introduction to his subsequent Italian translation, Valverde wrote:

Succeſſe dapoi, che molti non intendando la lingua Spagnuola, & vedendo le mie Figure non molto diuerſe da quelle, cominciarono á dire ch’io hauea tradotta l’historia del Veſſalio.

Many of those who did not understand the Spanish language, and who saw that my illustrations were not very different from his began to claim that I had just translated the work of Vesalius (translation by Bjørn Okholm Skaarup in Anatomy and Anatomists in Early Modern Spain).

Valverde longed to prove the inaccuracy of the accusations against him, including Vesalius’s, thereby validating his work as original. Though it conversed with and pulled material from other books, Valverde corrected or complicated that material, always treating it as the building block to his own larger argument. Throughout his own book, he corrects Vesalius’s images in nearly every account, improving on or adding details that he claims Vesalius grossly overlooked, most especially in the eyes, which he and other anatomists argue Vesalius universally mislabeled.

Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica, Bartolomeo Euctachi’s Tabulae anatomicae, and Juan Valverde de Amusco’s Anotomia del corpo umano will be on display in the Fearrington Reading Room at Wilson Special Collections Library as part of RBC’s Anatomy Day Open House. Please join us from 12:00pm – 2:00pm on Tuesday, November 12, to view historical representations of human anatomy in selected materials from our collections.