The Rare Book Collection is pleased to celebrate Women’s History Month by highlighting two recent acquisitions by notable female authors. It just so happened that last month, we were in the right place at the right time to acquire two exemplary works by women writers. Adding to the serendipity of it all is the fact that the books in question were published within a year of one another, in 1688 and 1689.

The earlier volume is Jane Barker’s Poetical Recreations: Consisting of Original Poems, Songs, Odes, &c. with Several New Translations (London, 1688). According to Kathryn King’s book Jane Barker, Exile: A Literary Career 1675-1725 (Oxford, 2000): “By any reckoning Jane Barker was a remarkable figure. A devoted Jacobite who followed the Stuarts into exile, a learned spinster who dabbled in commercial medicine, a novelist who wrote one of very few accounts of female same-sex desire in early modern Britain, she was also one of the most important women writers to enter the literary market-place during the Augustan period.” Poetical Recreations is her only volume of verse, and our particular copy of it is an appealing one, complete with the license leaf bearing the woodcut publisher’s device.

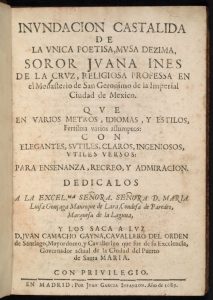

Our second acquisition was published the following year in Madrid and is nothing less than the first book of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, widely regarded today as the first published feminist of the New World. A child prodigy who was born in Mexico in the middle of the seventeenth century, Sor Juana has been lauded as the most outstanding writer of the Spanish American colonial period. In the twentieth century, scholars rediscovered her poetry, and she is now taught as part of the Baroque literary canon, including here at UNC Chapel Hill. Indeed, UNC’s Prof. Rosa Perelmuter is the author of two books on Sor Juana: Noche intelectual: la oscuridad idiomática en el Primero sueño (Mexico, 1982), and Los límites de la femineidad en Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: estrategías retóricas y recepción literaria (Pamplona, 2004).

The volume that the Rare Book Collection has purchased is, quite wonderful to say, the first edition of Sor Juana’s first book, Inundación castálida de la única poetisa, musa dézima, Soror Juana Inés de la Cruz, religiosa professa en el Monasterio de San Gerónimo de la Imperial Ciudad de México (Madrid, 1689). This rare edition is truly a touchstone for those studying Spanish and New World literature, and we look forward to sharing it with students and scholars.

Both Inundación castálida and Barker’s Poetical Recreations build upon RBC’s strong holdings of women writers and give witness to the enormous literary contributions of women over the centuries.