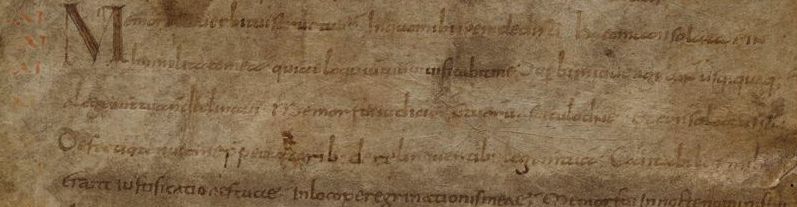

Lisa Fagin Davis’s popular virtual road trip has reached the Carolinas. Enjoy learning about some of UNC’s great medieval treasures, including one of its oldest Western manuscripts, a detail of which is shown above. Go to the lively blog and read the entry for this week, Carolina on My Mind.

Lisa Fagin Davis’s popular virtual road trip has reached the Carolinas. Enjoy learning about some of UNC’s great medieval treasures, including one of its oldest Western manuscripts, a detail of which is shown above. Go to the lively blog and read the entry for this week, Carolina on My Mind.

Month: August 2014

Tracing the Sinhala Script in the Rare Book Collection

The Rare Book Collection at UNC is proud of its global collections. Recently, we discovered a rare Sri Lankan imprint in our main library, Davis, and have arranged for its transfer to the RBC. The book, The Singhalese Translation of the New Testament (1820), is one of the earliest British books printed in the Sinhala language and a wonderful complement to the RBC’s collection of Sinhala olas, or palm leaf manuscripts.

Printing was introduced to Sri Lanka by the Dutch in 1734. The first book printed in Sri Lanka was published in 1737 using the first set of movable Sinhala type, which had been designed and cast by a local Dutch armorer. The Dutch printed a scant 22 books in Sinhala before ceding Ceylon (as it was then known) to the British in 1796. Although the British government took over the Dutch printing house and the Sinhala type founts, it was the religious societies—first the Columbo Auxiliary Bible Society (1812) followed by the Wesley Mission Society (1815)—that continued to print in the Sinhala language.

The Singhalese Translation of the New Testament is a major revision of an earlier, error-riddled edition published by the Colombo Auxiliary Bible Society in 1817. Much energy and money was devoted to the second edition, and a smaller, more compact Sinhala type font was specially commissioned for the octavo edition you see here. This book was intended to be widely distributed and easily carried. Printed at the Wesley Mission Press by a trained printer, this edition found praise among contemporaries for its typographical cleanness and elegance, as indeed it was by colonial standards.

By comparing an ola manuscript with the typography of The Singhalese translation, it is possible to study the relationship between Sinhala manuscript and print cultures. Scholars have argued that the rounded curves of the Sinhala script originated from the material constraints of writing on variegated palm leaves with a reed. Recently, Sri Lankan scholar and typography designer, Sumanthri Samarawickrama Jayaweera, has argued against such a reductive conclusion. You can listen to her engaging interview about the history of Sinhala printing and typography here. Jayaweera suggests that it was the introduction of colonial printing that ultimately changed how the Sinhala script was written—a process that might be traced in the RBC’s “new” copy of The Singhalese translation of the New Testament.

UNC’s ola collection, a gift of Dr. W.P. Jacocks, is not currently recorded in the online catalog but is described in H.I. Poleman’s Census of Indic Manuscripts in the United States and Canada (1967).

Poets of the First World War

Here at the Rare Book Collection we are gearing up for the centennial of World War I, and we’re expecting an influx of students, scholars, and other curious visitors to work with our extensive international holdings of related materials. To prepare, we are combing the collection, assessing what we have, and looking for those special items that might be of particular interest.

One item of note is a first edition of Siegfried Sassoon’s The Old Huntsman and Other Poems, Sassoon’s first book of poetry about his experience at the front. Sassoon published this volume in 1917, the same year he began treatment for neurasthenia (more commonly known as “shell shock”) at the Craiglockhart War Hospital, where he met fellow poet Wilfred Owen.

Sassoon’s poems, at their most caustic, register his disgust with war authorities in Britain, whose casual use of propaganda from the safety of the home front Sassoon critiques. Other poems, like “To His Dead Body,” convey his deep affection for his fellow soldiers while unflinchingly recording their deaths: “When roaring gloom surged inward and you cried, / Groping for friendly hands, and clutched, and died, / Like racing smoke, swift from your lolling head / Phantoms of thought and memory thinned and fled.”

What makes our copy—a second printing of the first edition—special is that it reveals how Sassoon used his time at Craiglockhart to create literary networks with fellow poets. Pasted to the back endpaper is a letter from Sassoon to Douglas Ainslie, a Scottish poet who was known to Oscar and Constance Wilde as well as Arthur Conan Doyle. In the note, written on Craiglockhart stationery, Sassoon tells Ainslie that he regrets not being able to meet him for lunch but says he hopes they can meet at a later time. Sassoon admits that he is “keen to know whether you like my poems, & equally impatient to read your own.” Ainslie’s autograph on the front endpaper suggests that the book was his. All the pages are cut, so we can surmise that Ainslie read Sassoon’s work. One can only wonder what, in fact, he thought about it and whether the two men got the chance to meet!

We are most grateful to the Estate of George Sassoon, Siegfried Sassoon’s son, for kindly granting permission to reproduce this letter. Readers who wish to publish the letter should contact the estate.

The Rare Book Collection has print holdings of many World War I writers, in addition to the extensive Bowman Gray Collection of World War I posters, postcards, and pamphlets, as well as other documents relating to the war. We welcome readers to explore our holdings in the second floor reading room of Wilson Library.