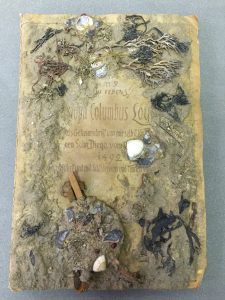

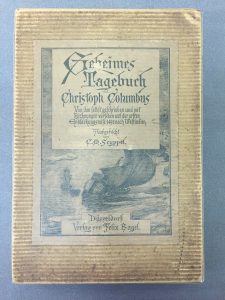

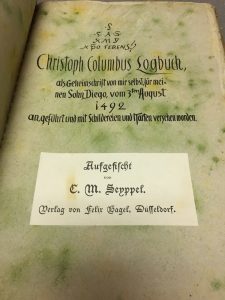

Recently added to the Rare Book Collection and now fully cataloged is Carl Maria Seyppel’s Christoph Columbus Logbuch, or Christopher Columbus’ logbook, one of a number of Mumiendrucke (mummy prints) created by the German author and artist. Some scholars believe that Seyppel’s work was a forerunner for the modern comic, and looking through this particular piece and others that have been digitized, that seems a valid assumption (Grüner 7). A Mumiendruck is a work that has been printed on paper and processed to look old, even adding elements, such as sand and seaweed in this case, to add to the aura of aging. The paper is deliberately destroyed and stained to make it appear older than it actually is. Carl Maria Seyppel is the most prominent figure in this form of book-making.

In fact, the 1882 patent for Seyppel’s method of making the paper for his works appear decayed reveals a great deal about his work:

“Um humoristische Erzählungen etc., welche von alten Begebenheiten handeln, mehr wahrscheinlich oder interessanter zu machen, bemühte man sich, dem zu diesem Zwecke verwendeten Papier das Aussehen zu geben, als ob es sehr alt wäre.” (In order to make humorous tales that are about past events seem more real or more interesting, one makes an effort to give the paper used for these purposes the appearance of being very old.)

The patent then goes on to describe the process to make new paper appear old in great detail. It was a rather complicated process that involved first saturating the paper with dye, sponging it off, and drying it to make the paper look moldy and decayed, then pouring alcohol along the edges of the bound papers and lighting them on fire to create uneven edges.

West-German collector Reinhard Grüner writes on Seyppel’s work, commenting that he “zerstörte bereits in den achtziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts die Auffassung, was ein Buch zu sein habe” (already destroyed the conception of what a book should be in the 1880s) (Grüner 7). Seyppel’s work was revolutionary in that sense, and his texts have posed problems for libraries and librarians from the beginning. For an interesting and extensive foray into Seyppel’s works, both German and English “translations,” see Tom Trusky’s work.

Looking more closely at the text itself will reveal much about Seyppel’s work and its place in literary history. Notably, this Mumiendruck marked the end of Seyppel’s mummy printing, as it was very unsuccessful (Trojahn 396).

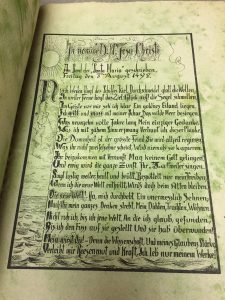

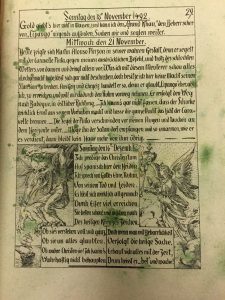

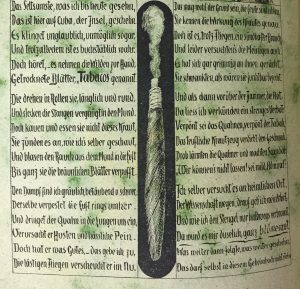

Written in rhymed text and intended to be a humorous parody of Christopher Columbus’ original journal, it begins, as the original did, on August 3rd, 1492. It is illustrated throughout and contains abbreviations typical of the fifteenth century and a command of the German language reminiscent of Goethe. The text is given the appearance of having been written by hand, and the edges of the pages are flecked with sand and jagged. The paper itself has been made to look as if it was once coated in seawater and salt, with green stains throughout. It reveals the innermost thoughts and desires of Christopher Columbus, mainly to conquer the New World, smoke its tobacco, and drive out the indigenous devils in the name of religion.

Interestingly, classifying Seyppel’s works was already a problem under consideration by librarians. An entry in The Nation from December 11, 1884, states:

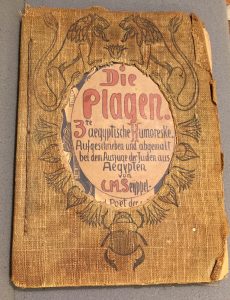

“Librarians must decide whether the mummy-cloth literature of German invention is adapted to their shelves or to easy classifying. The public will continue to be amused by a talent so original as that of C.M. Seyppel’s, and, we can now add, so fresh.” The “pure humor” present in his rendition of the plagues of ancient Egypt does not allow the author to “predict an exhaustion of the vein,” and this vein continues in Seyppel’s work on Christopher Columbus. (The Nation 503).

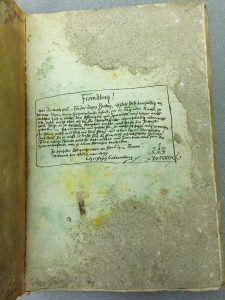

There is some lore that some non-German speaking catalogers were tricked and dated the piece to 1493 from this inscription, but fear not, it has been cataloged correctly in OCLC.

Check out our record and stop by Wilson to experience sand, seashells, and seaweed that is over one-hundred years old!

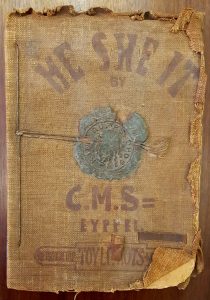

Should you be interested, two additional works by Seyppel, from his Egyptian trilogy, reside in UNC’s Rare Book Collection and in Duke’s Rubenstein Library: He-she-it, the English translation of Er-sie-es, an “Egyptian Court Chronicle,” and Die Plagen, a ficticious account of the plagues and the exodus of the Jews from Egypt. Both were printed in 1884 using Seyppel’s patented aging techniques. Below are a few images for comparison:

All translations are my own.

One thought on “Mummy Printing in the Rare Book Collection”