We are glad to present a guest post from scholar Genevieve Hay, recipient of a research award to work with sound recordings in the Southern Folklife Collection made accessible as part of our ongoing project, Extending the Reach of Southern Audiovisual Sources. Both the project and Ms. Hay’s visit are funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

A few months ago, I had the pleasure of making a research trip to The Wilson Library and the Southern Folklife Collection’s audiovisual archives. As a literary scholar whose research focuses on the intersections of literature, music, and social change, I was especially eager to review the SFC’s Highlander Research and Education Center Collection. The Highlander Folk School has served as a major hub for civil rights and labor activism since the 1930s. Under the guidance of musical directors like Zilphia Horton and Guy Carawan, the school also contributed to music’s pivotal role in the civil rights movement.

The SFC’s archives feature a range of music, stories, and interviews recorded at the school. These recordings offer insight into the kinds of hymns and music that Highlander collected and shared in its early years. Thanks to a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the work of the SFC team, many of these items are now available to stream online.

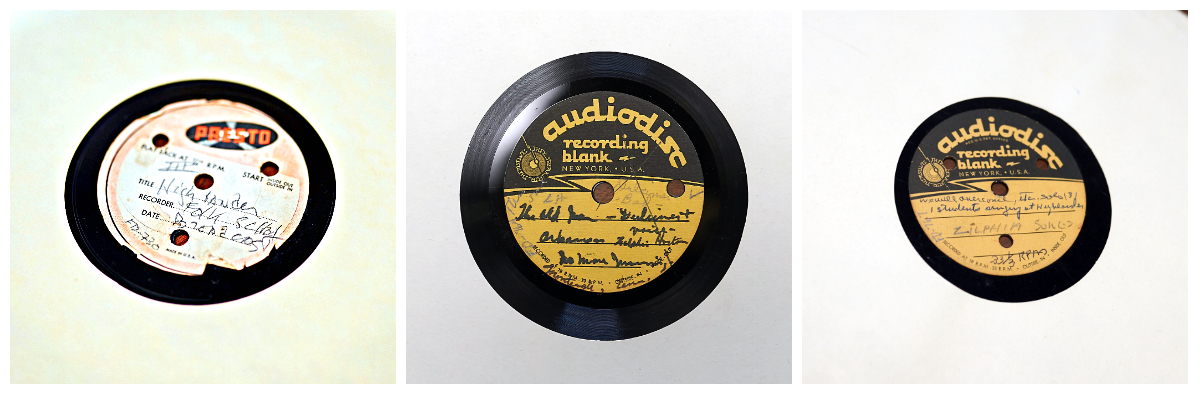

In this week’s “Field Trip South,” I wanted to share a few of the hymns and spirituals from these early recordings. Embracing the long-standing tradition of using religious music to protest worldly injustices, participants at Highlander gathered songs from across the South and arranged new adaptations. Indeed, the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome” came into the national spotlight thanks to collaborations between local leaders and the Highlander staff: factory workers Anna Lee Bonneau and Evelyn Risher taught a version of the song they’d learned on the picket line in Charleston, SC to Zilphia Horton, who rearranged the song and shared it with others. You can listen to two variations of the song, then titled “We Will Overcome,” below. These recordings were digitized from Highlander acetate discs call numbers FD-20361/750 and FD-20361/754. Though these recordings focus on a single verse, the verses were often listed and performed together, as reflected in the songbooks Highlander produced. Some of these songbooks are included in the SFC’s Guy and Candie Carawan Collection (20008):

0:33 We will overcome, We will overcome,

0:39 We will overcome, some day.

0:47 Oh, down in my heart, I do believe

0:55 We’ll overcome, some day.

1:03 We’re off to victory We’re off to victory

1:11 We’re off to victory some day Oh, down in my heart,

1:23 I do believe We’ll overcome, some day.

0:31 We will overcome, We will overcome,

0:41 We will overcome, some day.

0:49 Oh, down in my heart, I do believe

0:58 We’ll overcome, some day.

1:07 The lord will see us through The lord will see us through

1:15 The lord will see us through some day

1:23 Oh, down in my heart,

1:28 I do believe

1:32 We’ll overcome, some day.

In another recording, Horton pairs “No More Mourning” with the hymn “Farewell to All Below”:

0:03 Farewell, farewell, to all below,

0:11 My savior calls and now I must go

0:20 I launch my boat upon the sea

0:28 This land is not the land for me

0:36 I launch my boat upon the sea

0:45 This land is not the land for me

1:00 No more mourning, No more mourning, No more mourning after a while

1:16 And before I’ll be a slave, I’ll be buried in my grave,

1:26 Take my place with those who loved and fought before

By abridging “Farewell to All Below” to the opening verse which stresses “this land is not the land for me,” Horton highlights the shared concern of the two hymns: that the world leaves little space for many people, particularly the formerly enslaved and their descendants, who taught the songs to Horton. Coupled together, “Farewell” and “No More Mourning” stress the isolation of the present and gaze towards a better future. With the affirmation “before I’ll be a slave / I’ll be buried in my grave,” the song also expresses a determination to act. Furthermore, the declaration “I’ll take my place with those who loved and fought before” calls up and celebrates the emancipatory power of joining together. It is precisely these concerns that echo throughout the recordings in this collection: a balance of rallying optimism and engaged critique.

These are, of course, only a few examples from the SFC’s extensive collection of materials from and about Highlander. For more history and music from the Highlander school, check out the numerous streaming links available through the Highlander Collection finding aid. You can also browse the Guy and Candie Carawan Collection for more insight into Highlander’s later years, or take a look at Aaron’s previous post about Guy Carawan’s work at Highlander and across the South.