[Over the next few weeks, the Southern Historical Collection will be sponsoring a series of booktalks (formally titled, “The Southern Historical Collection Book Series”). The book series will feature authors of recently-published books that are based on research done in the Wilson Special Collections Library. Topics of the presentations include: hearthside cooking, hillbilly music, and proslavery Christianity. For more information about these three events, please see our news release on the main library website.]

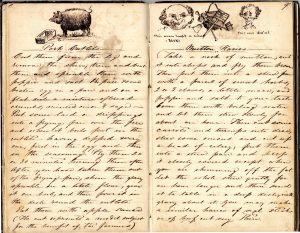

As a teaser for the first booktalk, a presentation by Nancy Carter Crump, author of Hearthside Cooking: Early American Southern Cuisine Updated for Today’s Hearth and Cookstove (UNC Press, 2nd edition, 2008), we would like to share a wonderful foodways-related item from the holdings of the Southern Historical Collection. The image shown at right is a page from an early-19th-century volume called “Recipes in the Culinary Art, Together with Hints on Housewifery &c.,” compiled by Launcelot Minor Blackford in 1852.

Launcelot Minor Blackford (1837-1914) of Virginia was a school teacher who served as a lieutenant in the C.S.A. 24th Virginia Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. In 1870 he became the principal of Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Va. Blackford was fifteen years old when he wrote this volume, which contains cooking and household recipes along with poems and advice. His advice on how “To make good Children” is as follows: “Whip them once every day; and give them plenty to eat. (One who has seen, and knows).”

This recipe book is a part of the Blackford Family Papers (SHC collection #1912).

I’m Southern and I’m talking about food, which means I am obligated to mention my grandmother! Several years ago, before she passed away, my grandmother wrote down and compiled a notebook of her best recipes. She called the collection, “Vera’s Vexing Victuals.” One year for Christmas, each of her grandchildren received a copy of this notebook. I still cherish my copy. Who knows? It might even end up in an archive someday.

All this leads me to this simple question: if you could preserve one family recipe for eternity, what would it be? Without question, I would preserve my grandmother’s recipe for chocolate silk pie.