A guest post by Emma Rothberg, a PhD student in UNC’s History Department.

When people think of the American Civil War, they generally conjure up images of battles. The flags, the cannons, the puffs of smoke, troops steaming across the landscape in varying shades of blue, gray, and butternut—the heat of battle is very visual. However, Civil War soldiers spent most of their time off the battlefield in camp. Between the marching and military exercises, soldiers of both the Union and Confederate Armies had a lot of free time.

Thousands of men, generally between the ages of 18 and 45, found many ways to pass the time. Some men played cards or dice with their fellow soldiers. Others played music and wrote letters or in diaries. In some cases, they played baseball. Other men were more creative. Ken Burns’s documentary The Civil War includes a vivid description of men finding entertainment in the lice that littered their clothing and hair; by heating up a tin plate from their packs, soldiers could make a quick buck by racing and betting on the lice they pulled from their bodies.

Other men sketched. Some soldiers included small sketches in letters home while others had more ornate sketchbooks. They sketched what they saw—the landscape, the camps, the fortifications, their fellow soldiers, or the aftermath of battle. Some sketched in black and white with pencils while others create more vivid watercolors. Civil War sketchbooks are not only beautiful but give insight into the preoccupations of a soldier’s day-to-day experience.

Wilson Special Collections Library has two wonderful examples of the types of sketchbooks soldiers kept while serving in the Civil War. Both of them are from Union soldiers, which may be an unexpected holding for an archive located in North Carolina. The first sketchbook was by Herbert Eugene Valentine (1841-1917), a private in Company F of the 23rd Massachusetts Volunteers. He served in the Union Army from 1861-1864 in eastern Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. (See the finding aid, with a link to the digitized sketchbook, here.)

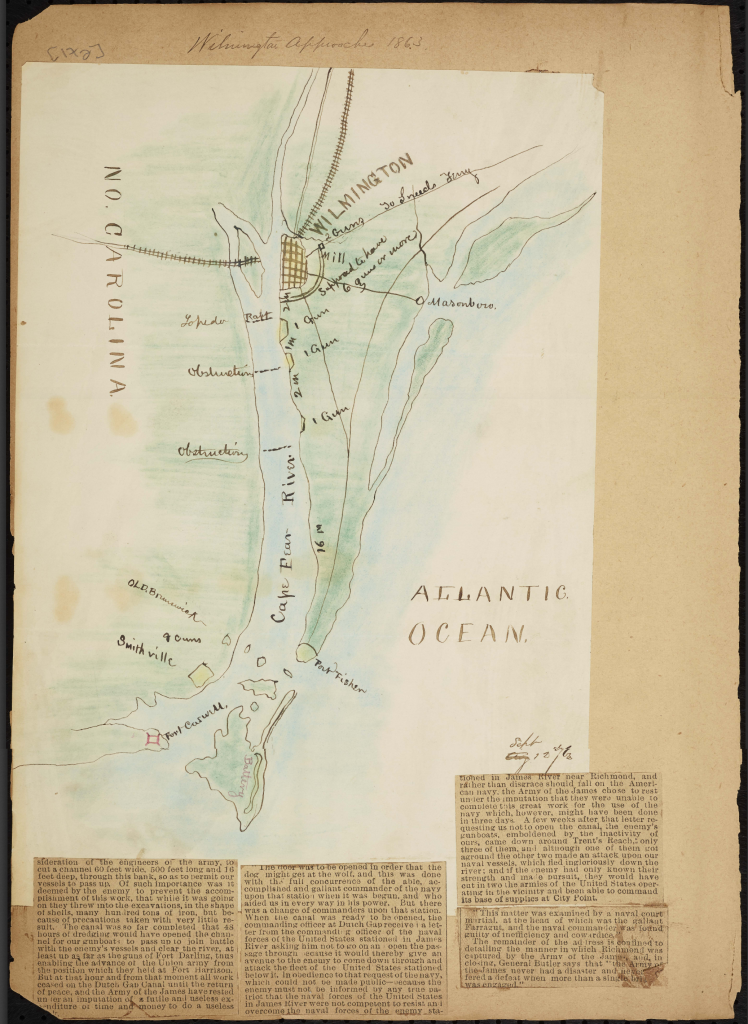

Pasted in between newspaper articles, his own writings, and newspaper photos of famous Union Generals and President Abraham Lincoln are sketches Valentine made during his time in the Union Army. Many are of landscape: a drawing of the harbor in Newburne, NC shows the church steeples and ships tucked in among neatly drawn houses (pg. 92). Others look more like cartographic maps, such as the image below of the North Carolina coast around Wilmington (pg. 52):

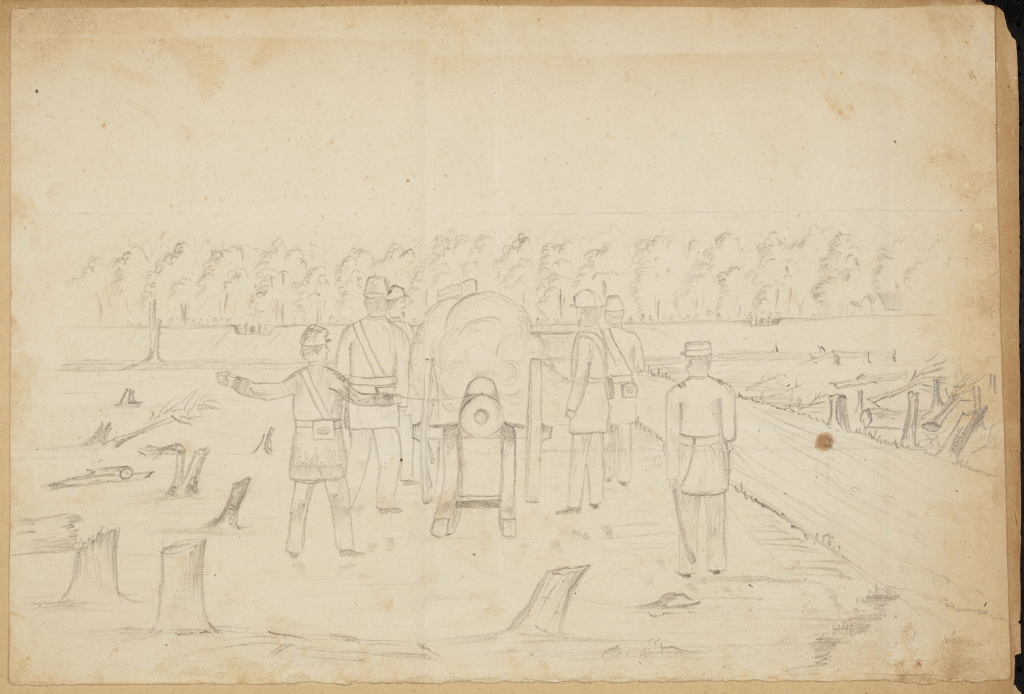

But Valentine also drew his fellow soldiers in extraordinary detail. Labeled “1st gun fired at New Berne,” Valentine carefully drew an artillery crew in action. While Valentine captures the explosion of cannon in pen and pencil, the men doing the work are depicted serenely: standing like sentinels overlooking a vista (pg. 94).

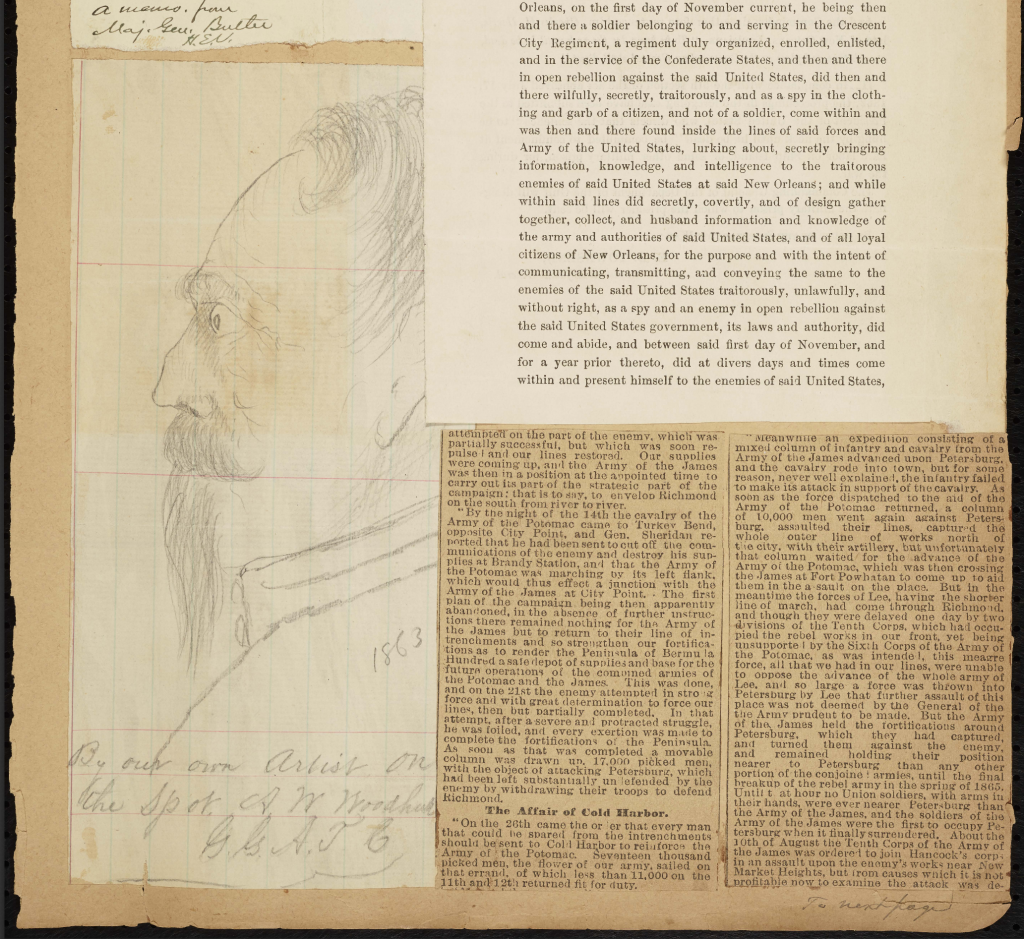

Valentine was not always so serious in his drawings and some included in his scrapbook could be classified as doodles. A personal favorite shows an unnamed officer’s profile drawn “By our own Artist, on the spot A.W. [Woodhull?] [GG] A.J.C” in 1863 (pg. 49). The man drawn seems almost startled; his eyes are wide as he stares off the side of the page.

Valentine pasted this drawing next to an article discussing the “Affair of Cold Harbor.” The Battle of Cold Harbor, which lasted from May 31 to June 12, 1864, included siege warfare, skirmishes and one of the bloodier assaults of the war (after a massive Union assault across an open field in the early morning of June 3, thousands of Union troops became causalities within an hour). The Herbert E. Valentine is fully digitized and viewable online through the collection’s finding aid.

Wilson Library also has the sketches of William Hedge, a lieutenant of the 44th Massachusetts Infantry that fought in North Carolina in 1862-1863. His collection includes six hand-drawn sketches made while in the vicinities of Washington and Williamston, N.C. (See the finding aid here.)

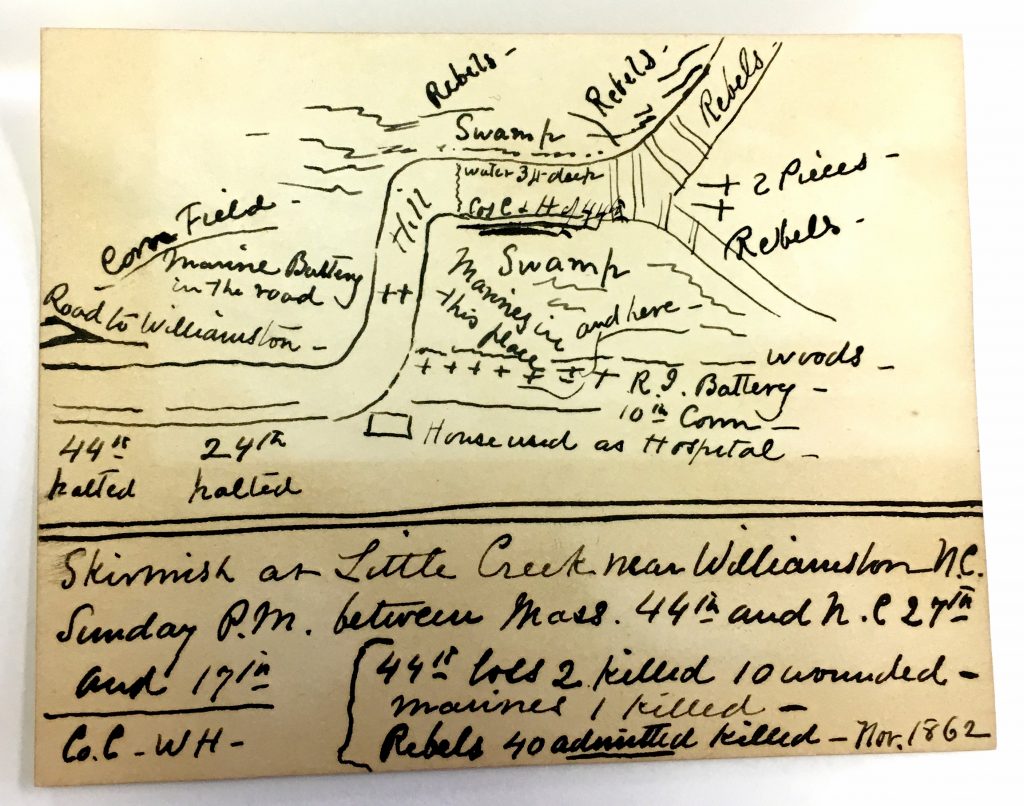

Like Valentine’s, Hedge’s sketches include a black-and-white map depicting the battlefield and troop placements of the “Skirmish at Little Creek near Williamston, N.C.” in November 1862.

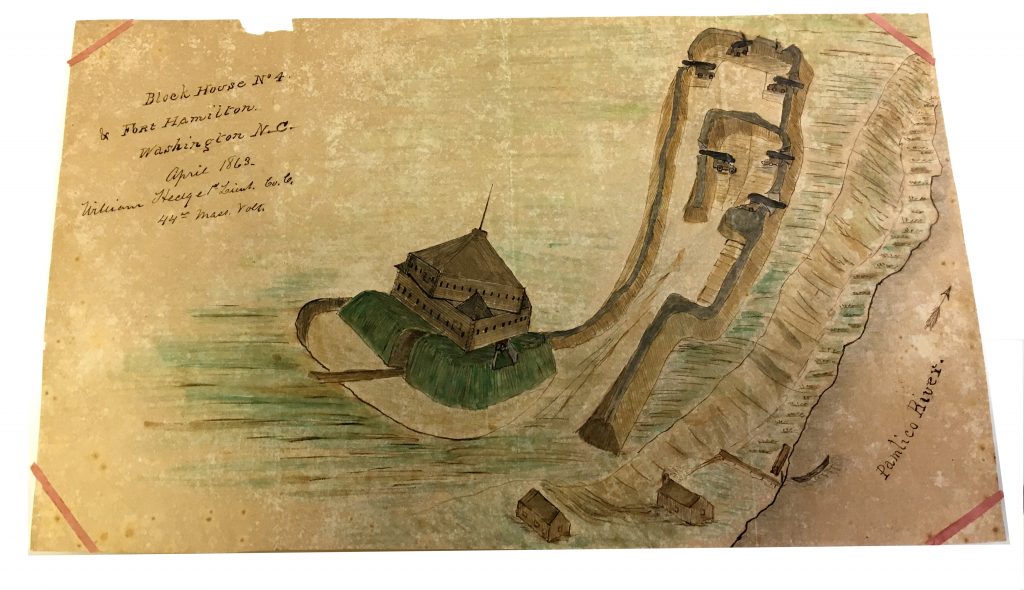

Another colored sketch is of the “Block House No 4” at Fort Hamilton in Washington, N.C in April 1863.

Perhaps the most interesting sketch included in sketch is also the one where the viewer is unsure as to what exactly Hedge meant to draw. A depiction of 1863 camp life at “Shellir Town” in North Carolina, a soldier sits off to the side minding a pot on a stove. Directly to his right on the other side of a small fire, Hedge draws the bodies of two men.

What is interesting is that they very well may be “bodies”—one of the men drawn, laying on his back, is almost corpse-like at first glance. While Hedge did not add any red to indicate blood, the viewer is left wondering if the two men on the right of the image are sleeping or slain. That Hedge could leave this vital bit of information up to debate might be interpreted in support of various arguments about Civil War soldiers. The drawn bodies laying next to a soldier cooking supports the argument soldiers became immune and/or unfazed by death as the war continued. The image also speaks to how “dealing with the bodies” became an issue and industry in and of itself. (For more on this latter point, see Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War). On a more positive note, if the men on the right are merely sleeping, Hedge’s sketch speaks to the commradery between men. They were a “band of brothers” both on and off the battlefield.

Plenty of maps, lithographs, and engravings were produced during the Civil War. These sketchbooks are unique because they remind researchers, students, and the interested observer of the humanity and individualism of the individual soldiers. It is easy to lose sight of the individual when talking about the mass numbers of men of each army during the Civil War. Yet these sketches allow us to connect with these men in ways in which facts and statistics do not afford. Like letters, sketchbooks allow us to see and tease out the individual and their experience. In the end, we all doodle.

Emma Rothberg’s scholarship focuses on the constitution of identity through cultural practices, in particular parading, in the nineteenth-century United States. She was awarded a funded Clein Graduate Summer Internship from the History Department to work with Wilson Special Collections Library for summer 2018. The Clein Internship allows graduate students to undertake self-identified summer internships in a broad range of organizations outside of traditional academia. As a Clein recipient, she has primarily worked on creating library guides to assist researchers and students who are planning to use UNC’s special collections. Emma has written library guides about the Civil War and Reconstruction.