On display at Wilson Special Collections Library since September, one powerful exhibit is nearing the end of its inspired look at the 400+ year history of the African American narrative and accompanying insight into ongoing implications for racial reconciliation today. On the Move: Stories of African American Migration and Mobility showcases personal accounts of several people across time in connection to various modes of transportation and, through this lens, invites patrons to examine the African American experience with physical and social mobility in the United States. Stories include those of enslaved Africans transported to the Americas by ship and escaping plantations on foot, African Americans migrating by train to new lives after the Civil War, traveling by car during the Jim Crow Era, and fighting for equality at Flight Schools and through Freedom Rides on the bus in the 1960s.

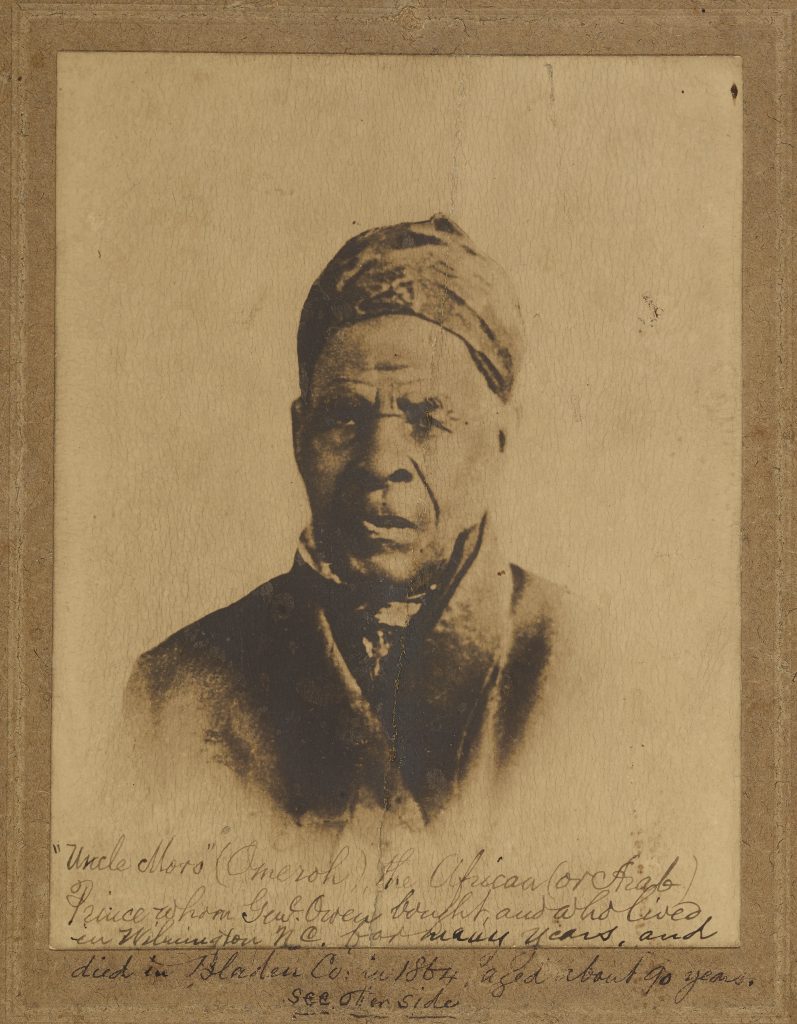

One of the exhibit’s highlighted narratives from the time of the Transatlantic Slave Trade is of special interest because his materials, like the exhibit itself, will soon be out of public circulation for a while. Omar Ibn Sa’id was an educated Muslim captured in 1807 from what today is Senegal. He was brought first to Charleston, South Carolina, but after an escape and later recapture in Fayetteville, North Carolina, was sold to plantation owner General James Owen in Wilmington. It was there he spent the rest of his life.

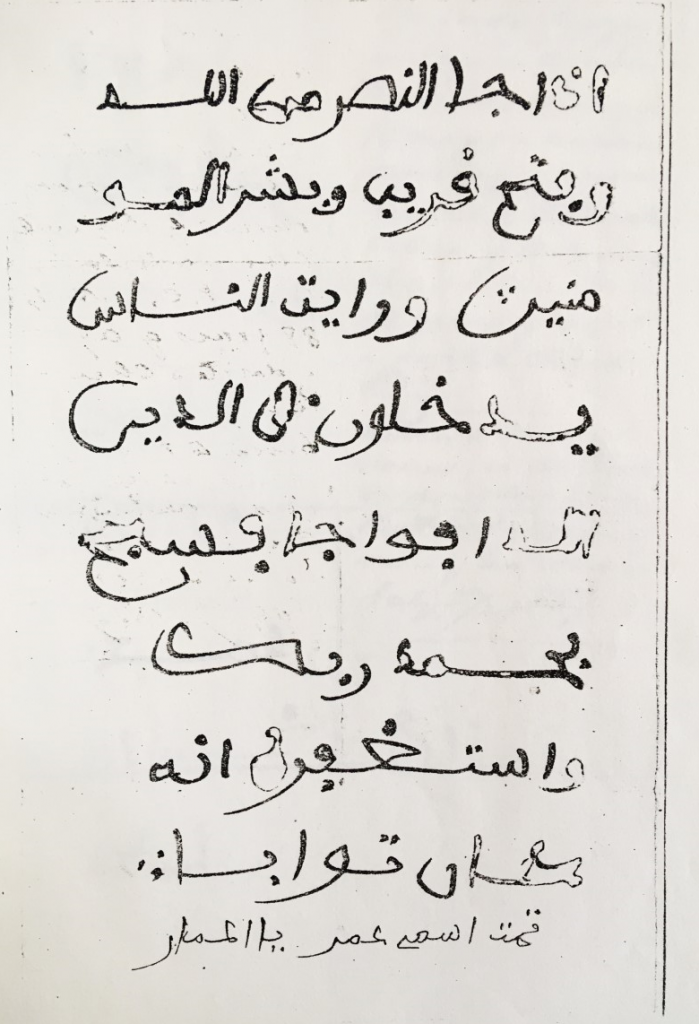

Ibn Sa’id’s legacy is perpetuated today among scholars fascinated by his story. He’s merited the role as an impactful topic of discourse for thinkers belonging to a wide range of disciplines. Exhibit curator Chaitra Powell, African American Collections and Outreach Archivist at Wilson Special Collections Library, attributes the reason for Ibn Sa’id’s popularity to his influence in challenging “perceptions of the intellectual history of Black people, educational and language traditions in Africa, the role of religion, and the lived experience of an enslaved person in the United States” (Display Case 2). Ibn Sa’id’s influence is recorded predominantly by way of his writings, including his autobiography published in 1831. As many were scribed in the Arabic language, they further lend support to the debunking of commonly held misconceptions about African people.

Of particular interest to me about his story in relation to the exhibit’s theme, which looks at the (sometimes forcible) transfer and movement of ideas, culture, and people, is Omar Ibn Sa’id’s supposed conversion to Christianity. Records place him as a regular attendee of a Presbyterian Church in Wilmington and confirm that he’d professed having converted. There exist, however, many different interpretations of the motivations behind this decision. Some suggest it was a matter of survival, while others propose he assigned little weight to religious affiliation—perhaps because he interacted with Islam and Christianity on the basis of their vast similarities (rather than focusing on their differences) or because the label itself was inconsequential to his faith in God.

The historical ambiguity of Omar Ibn Sa’id’s conversion creates space to address these uncertainties and ask questions. My own interpretation is that he approached this shift in religious affiliation as something independent of his worldview, a philosophy which strikes me as a powerful model relevant to our current climate of us-vs-them dispositions. It lends value to recognizing our shared humanity amidst a culture hyper-focused on differentiation. While the specificity of identity certainly matters, and labels can serve to communicate important truths about a person, they risk operating as tools for segregation when prioritized above commonalities between us. I believe Ibn Sa’id embraced this understanding in his forced encounter with a new culture, exhibiting strength of mind and character, goodness of heart, and self-autonomy while in bondage. In doing so, he rose above his captors.

This inspired story is but one of many featured throughout the exhibit, so we encourage you to visit On the Move: Stories of African American Migration and Mobility to explore, interpret, and learn even more! Its last day on display at Wilson Special Collections Library is Sunday, February 9th. Follow this link for more information: https://library.unc.edu/2019/09/on-the-move/.