Many home archivists and community-based researchers face a tough set of questions when deciding where their personal or organizational collections will live longer term. Not everyone is able to or wants to be responsible for the long-term care of archival materials, but many still wonder, “Who can I trust to be the steward of my important historical records?”

The answer is different for everyone, depending on what you are looking for in an archival steward. Stories from our Archival Seedlings program may offer insights and inform the questions you might want to ask to help guide your decision.

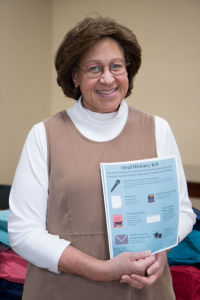

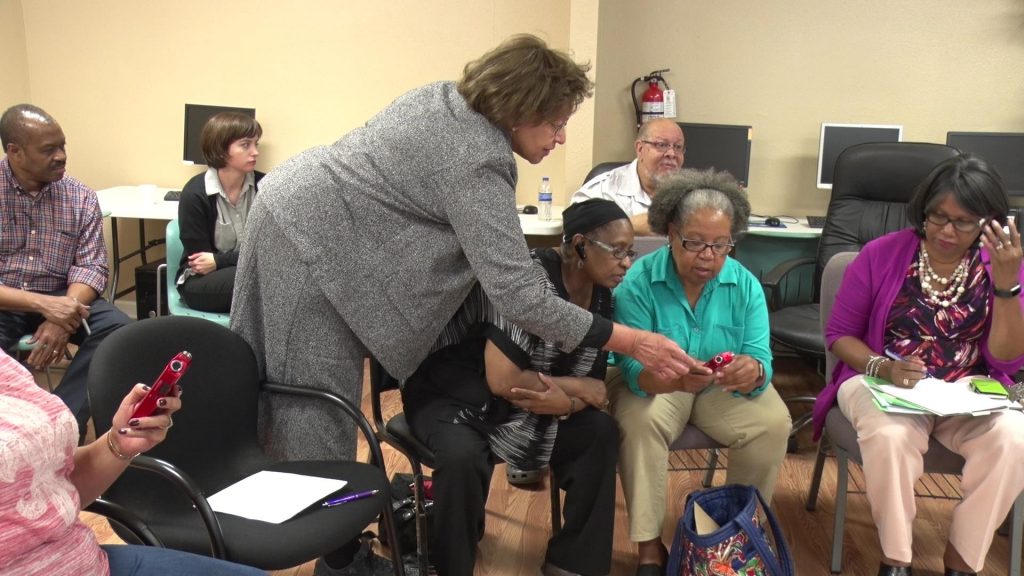

Since January, our Community-Driven Archives Team (CDAT) has been working with a group of ten researchers and budding archivists connected to our four community partners. We are supporting each researcher to learn new skills in working with historical resources. The skills they learn range from conducting oral histories to creating digital archives, and each researcher is developing a project of their choosing. Together, these researchers and their projects are the focus of a new initiative, the Archival Seedlings program. Participants in the program are known as “Seedlings.”

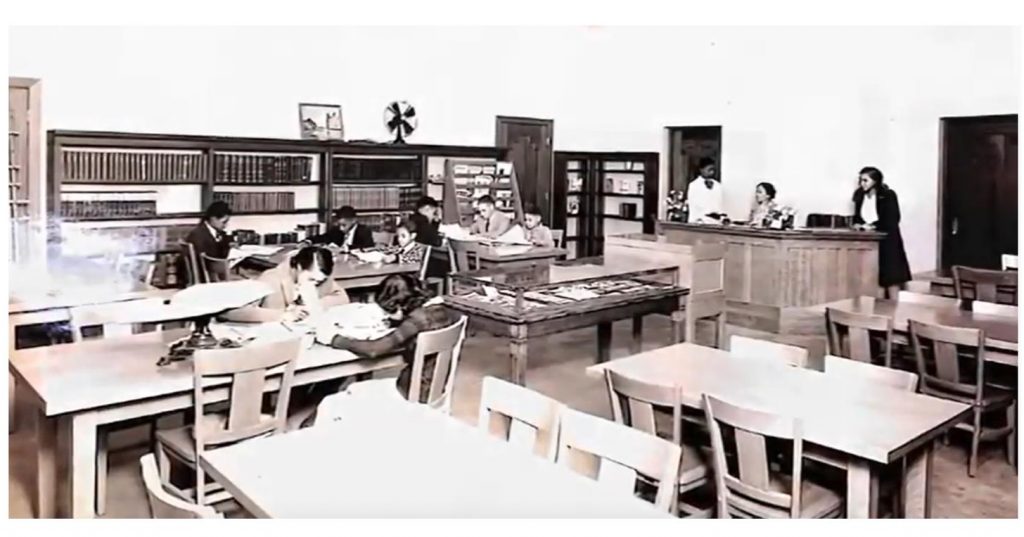

One Seedling, D.L., based in San Antonio, TX, is starting an archival collection on the life of Prudence Curry, the first director of the George Washington Carver Branch Library in San Antonio, the city’s Black library during Jim Crow. D.L. currently serves as the manager of Carver Library. Though Curry was a pathbreaking African American leader, very little has been formally documented about her life. Most of the stories about Prudence Curry live on in the memories of people in her community.

D.L. wants to make sure that Curry’s legacy will live on beyond individual memories through building an archival collection to benefit her wider community. He wants this collection to strengthen the preservation of Black history in San Antonio.

Luckily, D.L. is a member and researcher with the San Antonio African American Archive and Museum (SAAACAM), an independent community archive that has spent the past few years building up a staff and volunteer base in order to collect, preserve, and interpret San Antonio’s African American history. D.L. plans to send the beginnings of the Prudence Curry collection to SAAACAM, which he feels will be its perfect home.

But what if you don’t live somewhere with an independent community archive that is the perfect fit for your project?

Maybe you have decided that you want to preserve treasured historical materials for future generations, but also want to keep those collections in your community. How should you decide whom to reach out to?

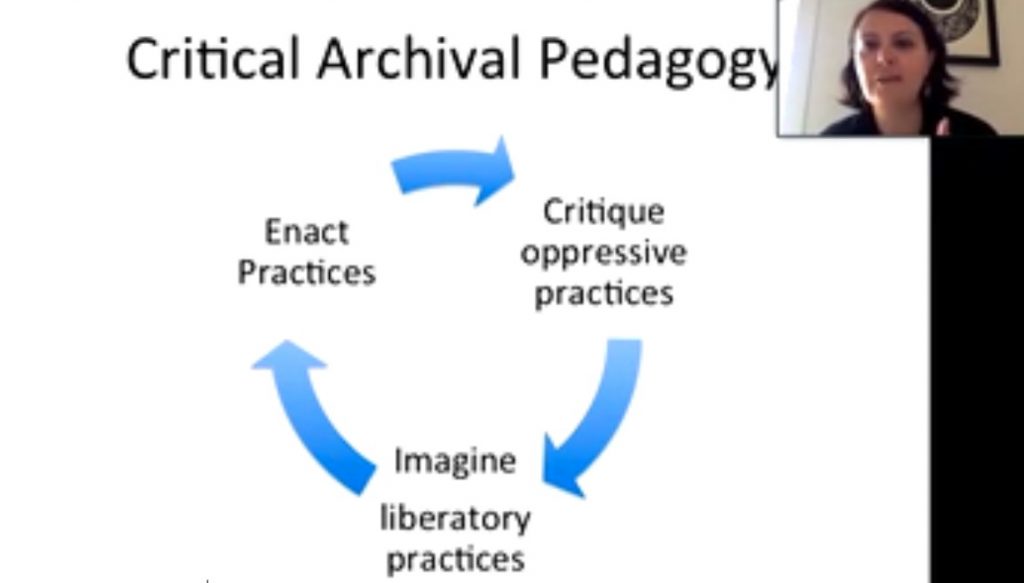

This is a question that some Seedlings program participants have asked themselves. It is also an important question in community-driven archives work; a central tenet of our approach lies in acknowledging that, for history keepers, sending collections to an academic archive, museum, or institution like UNC is only one option among many.

Another Seedling, Sylvia, based in Greensboro, NC, is creating an archival collection centered on local African American history during the Civil Rights era sit-in movement of the 1960’s. Specifically, she is conducting oral history interviews with a group of her former classmates and teachers at Dudley High School and North Carolina A&T State University who hold these stories in their memories.

Rather than donate her oral history collection to an institution that has been historically disconnected from her community, Sylvia has decided to pursue a partnership with a local Black-led community organization. She has decided that her collection will best live on under the care of an organization that has long been working directly for the betterment of her community.

When making a decision about where to preserve your cherished historic materials, considering asking yourself:

- What are my long-term preservation goals?

- How do they fit with the long-term interest and capacity of this potential partner?

- How long will this potential partner be able to retain the materials?

- How does this potential partner’s goals, values, and attitudes fit with my own and/or those of my community?

- How will community members be able to access collections materials in the future through this potential partner?

Then, consider how the answers to these questions affect your decision about where and with whom to partner. Remember, it is your and your community’s choice to decide on the best steward for your historical records.

Check out the short videos on the Resources page of our website to learn more about working with institutional and community-based archives to meet your needs.

For more about community-based archives on the Southern Sources blog:

Partnering with The San Antonio African American Community Archives and Museum (SAAACAM)

The Community-Driven Archives Project at UNC-Chapel Hill is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Follow us on Twitter @SoHistColl_1930 #CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC