In Fall 2020, through the generous support of the Kenan Charitable Trust, the Community Driven Archives Team had an opportunity to hire a graduate student, Angelique Marrero, to explore how the Libraries could leverage lessons from the Mellon grant into outreach efforts after the grant’s staffing and resources ended. Read about Angelique’s journey in her own words here:

My Background

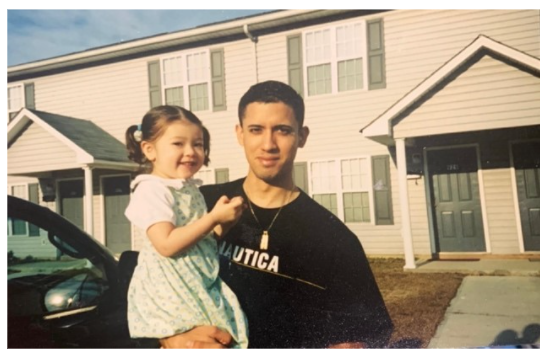

My time on the Community Driven Archives team has been full of twists and turns, and one of the most unique job experiences I’ve ever had. I was really excited to be a part of this grant because as a Latina from a close knit community I have seen how history and culture can manifest in different ways. Most of my childhood was spent in Fayetteville, North Carolina where both of my parents were stationed at Fort Bragg. Being a part of a close knit community that took care of each other helped me understand what true community was.

I loved how something that could seem unimportant to outsiders could mean the world to us, that kind of “insider knowledge” made me feel special. When I was given the opportunity to be a part of this grant it was no question that I wanted to be here.

Approaching Community Driven Archives with a Research Question

I joined the team with a project scope in place: connect with Black communities in North Carolina and learn how these communities would like their history preserved. I understood that there exists a historical marginalization and exclusion of Black voices in the library and archives. The traditional archival process involves the library taking the artifact and giving context to it in their own separate repository which often leads to misrepresentation and misinterpretations. Our central research question became: Given our geographic, staffing, and institutional boundaries, alongside community priorities; how can we support the collecting, preserving, and sharing of Black community voices in North Carolina? That’s a big question and while we knew our research would not cover every aspect of this question, the hope was that it would begin the conversation that would lead to more projects and different viewpoints.

A Research Journey

Once we established this question, we needed a way of forming relationships with Black communities in North Carolina and narrowing a sample few communities with whom to conduct interviews. We acknowledged early on that our readiness to pursue this line of inquiry did not equate to the availability of community members for us to talk to. Through conversations with Community Driven Archives Team members and staff from the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center, I learned how some African American communities identified themselves (alumni of segregated high schools, neighbors in a coal mining community, etc.) and value they placed in archiving their stories for future generations. I wanted to find more African American communities that had this strong sense of interconnectedness and heritage.

The Rosenwald School Connection

As a team we decided to focus in on the linkage of Rosenwald Schools (NC Museum of History) that was a massive project that occurred between 1917 and 1932 when Julius Rosenwald left the initiative for the creation of nearly 5,000 rural schoolhouses in the south. Around 800 of those schools were here in North Carolina, however, many are no longer standing or have been converted into community centers or other properties. While this avenue did give us a narrower range of possible communities, it was still a very expansive list. But everything began to become clearer when I found an article discussing Lowe’s Charitable Fund Grants in North Carolina that were focused on the restoration of Rosenwald Schools that were awarded to community groups. Through this source we were able to pin three viable options for communities to contact that were actively invested in their community’s history and the preservation of that history.

Following the selection of possible candidates to interview it then became an adventure to find contact information for these groups and organizations. While I initially thought this process wouldn’t be too difficult, I ended up not being able to find up to date information that I could actually be able to contact to someone in the community. Many of the groups had Facebook pages that were inactive, old numbers/emails, were currently not active because of the pandemic or just did not have an online presence. After many dead ends, I began to get a little discouraged and the option of changing directions became a possibility.

Then one day I was looking into one of the last communities in Walnut Cove that had a restoration project led by two women, Dorothy Dalton and her sister Mary Catherine Hairston Foy, they were both alumni of the school. After some research I found out that both women had unfortunately passed away but a news article listed the daughters of Mrs. Foy, and I decided to reach out to one, Dr. Capri Foy, who I found on an employee registry at Wake Forest Medical Center. Initially I didn’t expect a response but a few days later I received a reply letting me know this was Mrs. Foy’s daughter and that she currently served as a board member on the Walnut Cove Preservation Board!

The Outreach

With this link to a community, we decided it would be helpful to do a focus study on this one place with Dr. Foy, as an enthusiastic leader. As we met and discussed various outreach programs and initiatives, we ran into difficulties in determining whose labor would be involved in bringing these projects together. For example, without a grant funded oral historian available to record the elders, the timeline for training community members and setting up interviews became untenable. We were also insistent on finding ways for the community to benefit from our engagement, but without an Archival Seedlings program to join, there weren’t any structured professional development or monetary incentives. The transparency that we were able to demonstrate felt strange at times, but it kept us from committing to projects that we weren’t fully prepared to execute. In the end, we determined that a full partnership was not feasible at this time but we would keep their needs in mind as our work evolved.

New Measures of Success

After reflecting on my time with this project I’ve realized that building these community and institutional partnerships is not always a linear process. We should act and react based on close listening, and not be afraid to re-calibrate. Community history is owned and shared by those in the communities, as an institution we are not supposed to control the outcome of these discussions. Instead, we are there to listen, learn, and follow the lead of these communities who are the experts in their own heritage.

As a graduate student, I was eager to support the community, but I think we needed more buy-in from library staff and leadership to make the community feel like they were a part of something more substantial. I also hope that we can do more with the Rosenwald School story as it is well documented in the archives/libraries and continues to have a high impact in communities, perhaps my research journey can be a part of another collaborative research or outreach project.

If our only goal was to find the conditions under which CDAT can work without external funding, we were not successful…and that is ok. There are other strategies to explore and other measures of success. Especially now, during this critical point in UNC’s history we successfully disrupted the silencing of Black voices, avoiding a negative precedent often employed in traditional libraries and archives. We did this by being honest with our potential partners about our capacity, encouraging them to make an informed decision about whether to proceed, and acknowledging that our community driven archives framework (as it is currently implemented) won’t always be the best option for every community.

Potential Next Steps

As I continue my time in the School of Information and Library Science, I will always be grateful for my time on the Community Driven Archives Team. I have never had a job where my input, decision making, and creativity was so valued by my leadership. I was often faced with a lot of choices on which way to take the project and while it may have led to a few dead ends, I learned a lot about myself and what it takes to lead a successful grant project. I am so excited to see this work continue with other projects and research; I hope that eventually community driven archives work can be fully resourced and serve as a main service for major universities to offer.