Last year, the Southern Historical Collection was pleased to make two collections available to the public, the William W. Dow Papers and the Richard Davidson Photographs of the Appalachian Student Health Coalition and the Mountain People’s Health Council. Both collections relate to the community of Vanderbilt alumni from the Appalachian Student Health Coalition, which began in 1969 to provide health fairs to rural communities without health care in Appalachia.

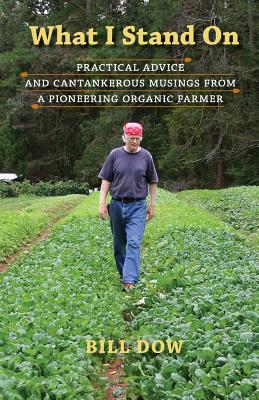

In addition to h is work as a doctor, William (Bill) Dow became the first organic farmer in North Carolina and the founder of the Carrboro Farmer’s Market (among many other accomplishments).

is work as a doctor, William (Bill) Dow became the first organic farmer in North Carolina and the founder of the Carrboro Farmer’s Market (among many other accomplishments).

Before his death in 2012, Dr. Dow recorded his thoughts on sustainable farming with the hope that it could be compiled into a book. His friend, Fred Broadwell, and his partner, Daryl Walker, completed this project resulting the book titled: What I Stand On: Practical Advice and Cantankerous Musings from a Pioneering Organic Farmer. It is now available for order at your local independent bookseller.

Though much of the book contains Dr. Dow’s pioneering farming philosophies, small mentions of the Student Health Coalition are peppered throughout.

Broadwell and Walker will be doing readings from the book at local bookstores during the next few months. If your interested in a pioneering farmer’s wisdom and philosophy, or perhaps enjoy homegrown food, please join them at:

- McIntyres Books in Pittsboro on Feb 27, 2016 at 2:oopm.

- Flyleaf Books in Chapel Hill on Feb 29, 2016 at 7:00pm .

-

Flyleaf Books in Chapel Hill on March 8, 2016 at 7:00pm. With an appearance byIsaiah Allen, the chef of The Eddy in Saxapahaw and owner of Rocky Run Farm, who wrote the book’s introduction.

-

Regulator Bookshop in Durham on March 10, 2016 at 7:00pm.

he Southern Historical Collection?

he Southern Historical Collection?