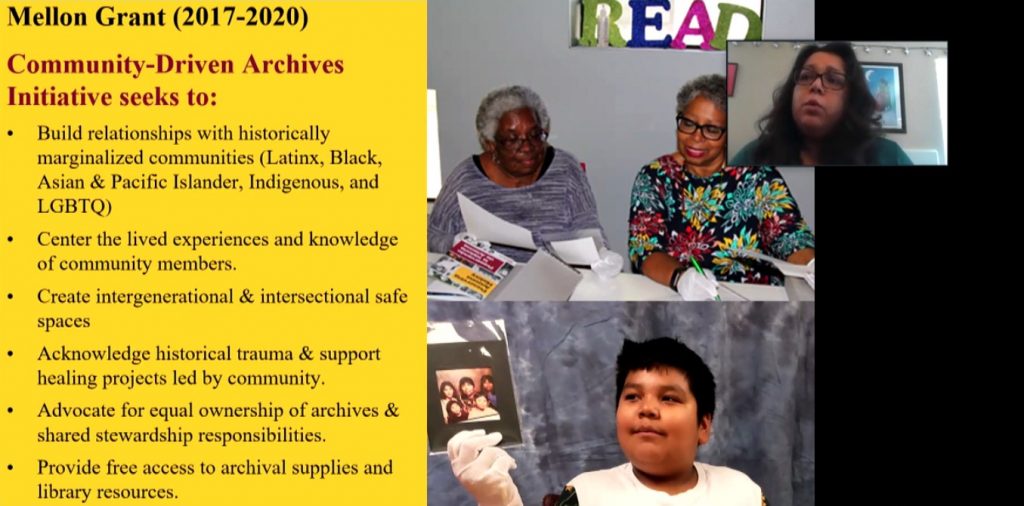

Throughout our grant-funded Community-Driven Archives project, our team worked in collaboration with our partners based on a guiding set of values that emphasized community benefit, reflexivity, service, and accessibility. Now that we’ve concluded the work on our grant, we are identifying ways that our short-term efforts can have a longer-term impact on the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill.

What might we take with us into the next chapter? What is our vision for community-driven archives when practiced at scale at an archival institution?

Free from the pressure and limitations of grant deliverables, our team started the process of imagining what our home institution might look and feel like through a community-driven archival lens. Below is a synthesis of some of our team’s conversations.

What might signal a Community-Driven Archives approach to library visitors and researchers?

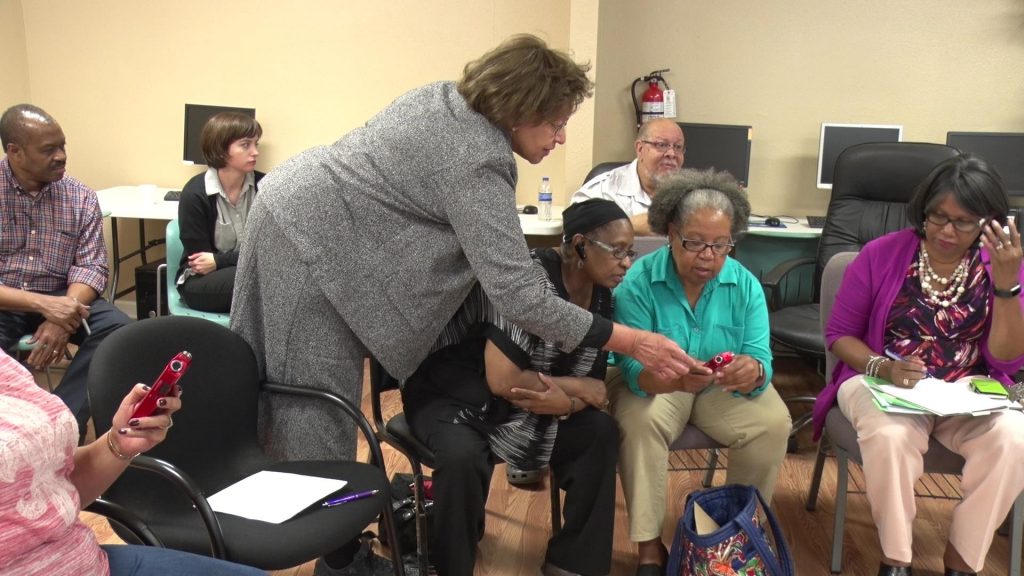

When a member of the public visits the library’s website or walks in the door of the library, they see announcements about upcoming events that pertain to some of their interests. They see an event invitation to a free community archives scan day at a local community center in partnership with the library. They see an upcoming Archives 101 training and skill-share hosted by an organization they are already familiar with, one connected to their neighborhood, identity, or hobbies—another community-library partnership. They see an announcement that a local community organization received a substantial grant to start a community archive with the support and ongoing partnership of the library. In addition to the library’s website and buildings, they see these announcements and flyers at various community spaces and public places they frequent, as well as through member groups’ web-based communications and social media.

What do these approaches have in common?

- They do not take place at an institutional library setting, but rather at community centers and spaces that our collaborators already frequent and feel comfortable visiting. A public library can feel more comfortable and accessible, for example, than an academic institutional library.

- They are all based on partnership with organized groups of people and and/or existing community organizations, rather than relying on one individual as the “go-between” or trying to recruit community members to attend an event based on a one-time interaction.

- They are based on a model in which the library is resourcing communities, with a focus on historically marginalized and underrepresented communities, through funding opportunities and staff support, rather than funding flowing first to the library and then to communities through library-branded programs.

When using the archives, what evidence might users see of a Community-Driven Archives framework?

When community researchers come into the library they are welcomed and asked if they need any specific help with their research project. They see staff working at the library in positions of leadership who look like them. If they are new library users, they are given a welcome sheet with information that might be helpful both to new archives users as well as to new researchers at the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill. This information is also clearly available and accessible on the library’s website, as well as through a printable PDF distributed to partner organizations. The welcome sheet covers topics like:

- What are the easiest ways to get to the archive?

- How will the library accommodate my access needs?

- How do I search the archive for what I’m looking to find? Who can help me?

- How do I request materials to look through while I’m at the archive?

- Why do I need to leave my belongings in a locker and stay in the reading room when I’m looking through archival materials?

- If I find something that I’m interested in, what are the best ways to keep track of it?

- How can I make a copy of items I find here?

- What are the best ways I can share what I find here with other people?

When searching finding aids, libguides, subject guides and other indexes of collections materials, users are able to search using terms for themselves and their communities that they use rather than outdated or, much worse, offensive terms. Searchable guides that do not meet these parameters might be labeled with content warnings and an acknowledgment from the institution that language found in the relevant guide is inappropriate and has been flagged for remediation. Users are encouraged to bring offensive or harmful language that they uncover through their research along with other access needs to the attention of the libraries’ staff through an anonymous online form and/or paper survey.

On the Carolina libraries’ website and through its communications with its users, the library shares recommendations of community-based digital and physical collections connected to historically underrepresented communities, peoples, groups, and events. It should make these recommendations of community archives projects alongside its own acknowledgement of the internal work that must happen institutionally to redress long-standing gaps and silences in its archives, towards repairing historic erasures.

What are the common threads of this archives experience?

- It centers an accessible archives experience for a broad base of people.

- It is attentive to the hiring practices of the library and emphasizes staff diversity across race, gender identity, sexuality, and ability.

- It owns up to past harms perpetrated by and through archival institutions and clearly communicates the steps being taken towards repair and redress.

- It invites users to share any access needs that will support a fruitful archival experience.

What could library outreach activities look like as part of a Community-Driven Archives experience?

A staff member at a local LGBTIQ center receives a call from a staff member at the library. The library staff person explains that the library has been contacting local groups and organizations to ask them about their work and to learn more about the groups and organizations in their area/region. They explain the resources that the library offers to community groups wanting to document their histories and/or preserve and share their historical materials. Those resources can also be found in a guide for potential community partners available online or as a physical brochure.

The staffer from the center shares the center’s history and what goes on there day-to-day. The library staff person asks if they might be interested in setting up a meeting to talk more about how the library might be able to support the center to share its history with its members and chosen audiences, and they take the next step to set up an in-person or Zoom meeting.

What are the important features of this interaction?

- The caller places the focus on the organization or community group and its history rather than on the services, goals, or interests of the institution. The library staff person wants to get to know groups in the broader community and to serve them — and makes that clear.

- The library does not make promises of support it will not be able to provide and clarifies what it is able to offer through a written list of available services in support of community partners. This list is made available to all potential partners and is kept up-to-date on the library’s website.

- Rather than try to secure immediate interest, the caller makes it clear that they want to spend time on building a relationship with this potential partner over time through physical or virtual face-to-face meetings.

How might our communication about our work shift under a Community-Driven Archives framework?

Library collaborations are branded in a way that cross-promotes our collaborators’ work and organizations. Collaborative projects are not branded with institutional colors, and staff members take steps to avoid colors, fonts, images, and related design choices that signal an academic and/or institutional audience to the exclusion of community audiences. When launching, announcing, or celebrating our collaborative achievements, our institution amplifies the work of our collaborators and directs our audiences to learn more about it. Our institution only takes credit for its share of the work and honors and champions the people, groups, and organizations who made contributions.

When we create communications content, we pay attention to voice, reflecting critically and reflexively on the institutional voice we use when reporting on our community collaborations. We look for ways to respectfully weave in the voices of our collaborators, especially when representing their work or stories. When our collaborators entrust us as stewards of their materials, stories, or collections, we make it a priority to promote those items, so as to reach our collaborators’ priority audiences in addition to our own.

What are the common threads of this approach?

- It requires institutional staff to be reflexive when representing collaborative work, taking into consideration the power of the institution and the benefits, responsibilities, challenges, and problems that come with it. Sometimes it means using the weight of the institution to direct people and resources in support of communities. Sometimes it means amplifying community voices rather than our own.

- It redirects the focus of our communications about our work to serve the goals of our community partners. It pays attention to our partners’ needs rather than those of our institution, donors, or funders. This shift in how we represent our work is communicated upfront to institutional and fundraising stakeholders.

- It makes design choices that signal a shift in our communications towards community benefit.

Throughout the harrowing challenges of 2020, our Community-Driven Archives Team has been in conversation with our

Throughout the harrowing challenges of 2020, our Community-Driven Archives Team has been in conversation with our