Chaitra Powell and I spent the last weekend of February traveling to Shaw, MS to conduct an Archivist in a Backpack Training and archival techniques workshop. We collaborated with a group working to preserve and share the history of the town of Shaw, specifically the civil rights case Hawkins vs. Town of Shaw. We met the group at the Delta Hands for Hope, pictured below, which runs programs for students and community members, but is also the base of operations for the Hawkins Project.

The power behind this community work is the team of Dr. Timla Washington and Jenna Welch. Timla, pictured below second from the right, is currently the Community Development Coordinator in the office of Congressman Bennie G. Thompson.

The power behind this community work is the team of Dr. Timla Washington and Jenna Welch. Timla, pictured below second from the right, is currently the Community Development Coordinator in the office of Congressman Bennie G. Thompson.

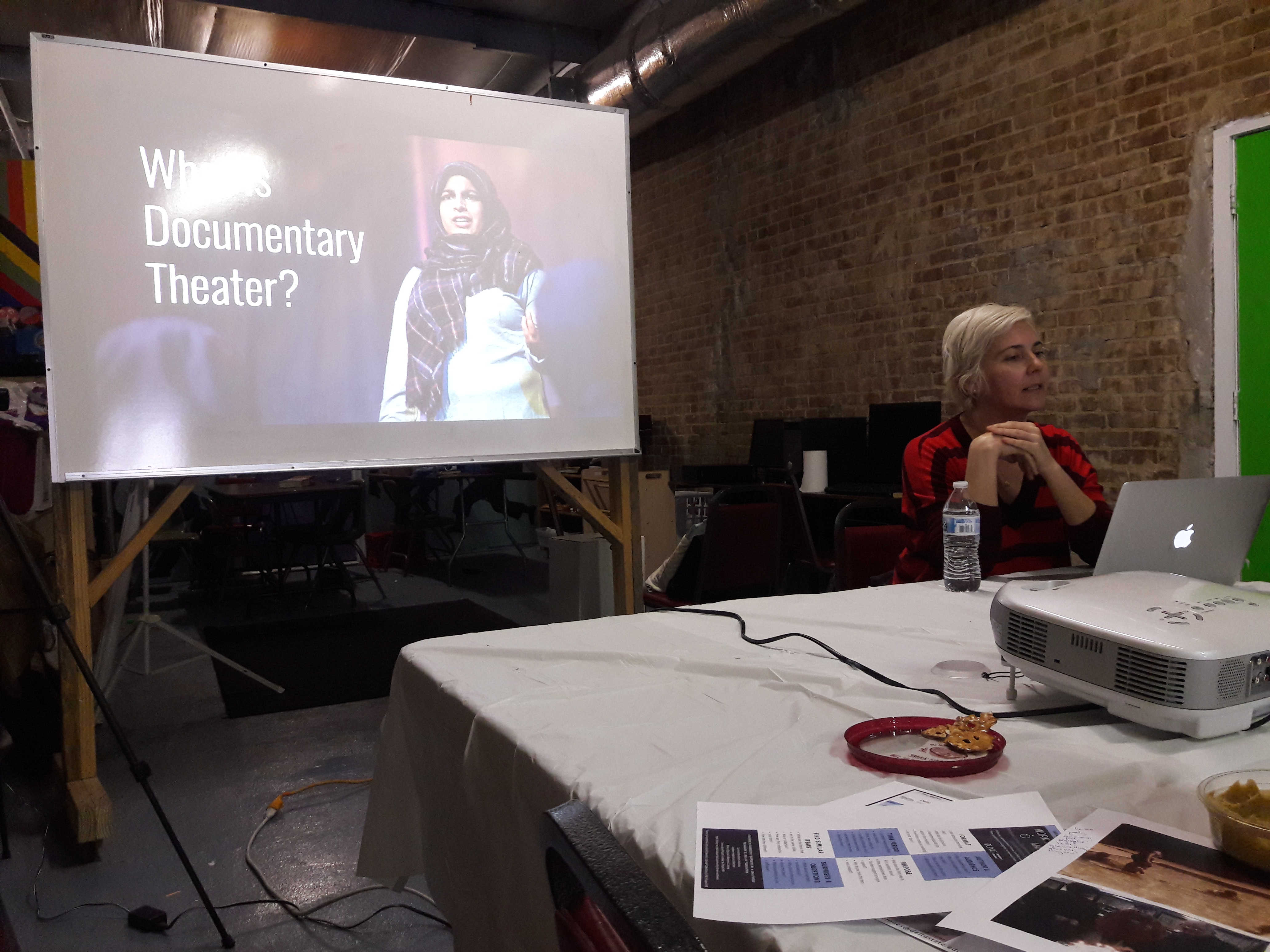

Jenna, pictured below, is the artistic director and co-creator of the company StoryWorks, which combines investigative journalism with documentary theatre.

These dynamic women have spearheaded an enormous project that combines archival materials, art and theatre, public health policy, and a myriad of other areas to tell the story of Shaw. Their work highlights the legacy of institutional racism incorporated into town infrastructure, and the failure of equitable legislature, despite a court victory for the African American population in Shaw.

Before this trip, I had a little knowledge of Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, and I certainly didn’t know that it was the first court case that used statistics to prove discrimination. Yet I quickly realized that Shaw, MS was in an area with numerous Civil Rights activities, for example, the site (pictured below) of a Freedom School, run by local farm workers and SNCC activists in 1965.

We flew into Jackson which is about a 2 hour drive to Shaw, so we spent a little bit of time exploring the city with Timla, Jenna, and Gloria Hawkins. While we didn’t make it to the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, we did see the Medgar Evers home and observe an oral history interview with one of the lawyers on the Hawkins v. Town of Shaw case in 1967. Gloria Hawkins is one of the daughters of Andrew and Mary Lou Hawkins, even though she was a teenager during the case, she has a file with the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission Database.

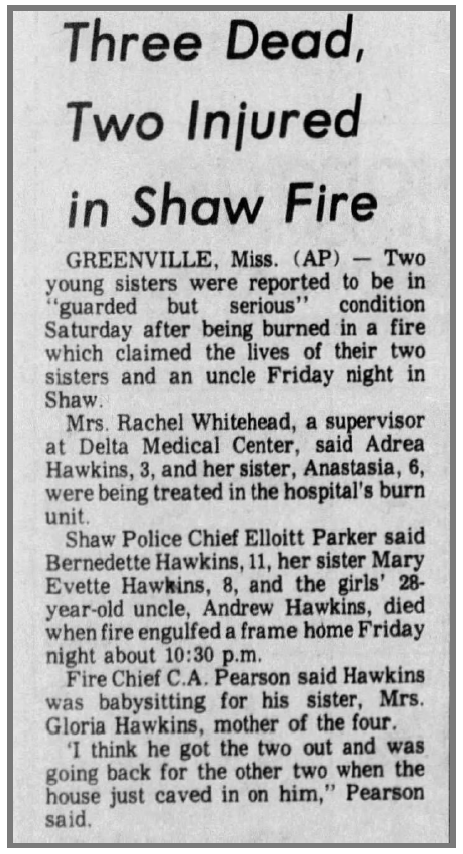

What I didn’t realize until that tour was that Mrs. Mary Lou Hawkins was shot and killed in 1972 by a police officer, or that the Hawkins’ home was firebombed twice after the case. In the 1979 fire, Andrew Hawkins Jr., 28, and two of Gloria’s daughters, ages 8 and 11, were murdered.

Newspaper clipping from the McComb, MS “Enterprise-Journal” March 18, 1979 reporting the house fire and deaths.

On Saturday we were a little concerned that the weather would affect attendance to the workshop as it had been heavily raining Friday night. It was surreal to stand in the streets of Shaw and see that all the work that the Hawkins case had accomplished could not combat the legacy and strength of discrimination. The Hawkins case had mandated more robust sewer, water, and street light infrastructure as well as paved roads for the African American part of town. That was in the 1960s and early 70s.

Infrastructure quality remains so poor in 2019 that entire sections of the town are unable to get out of their houses because of the flooding. That body of water on the edge of the neighborhood, pictured above, is a frequent occurrence, as is the flooding of homes and streets.

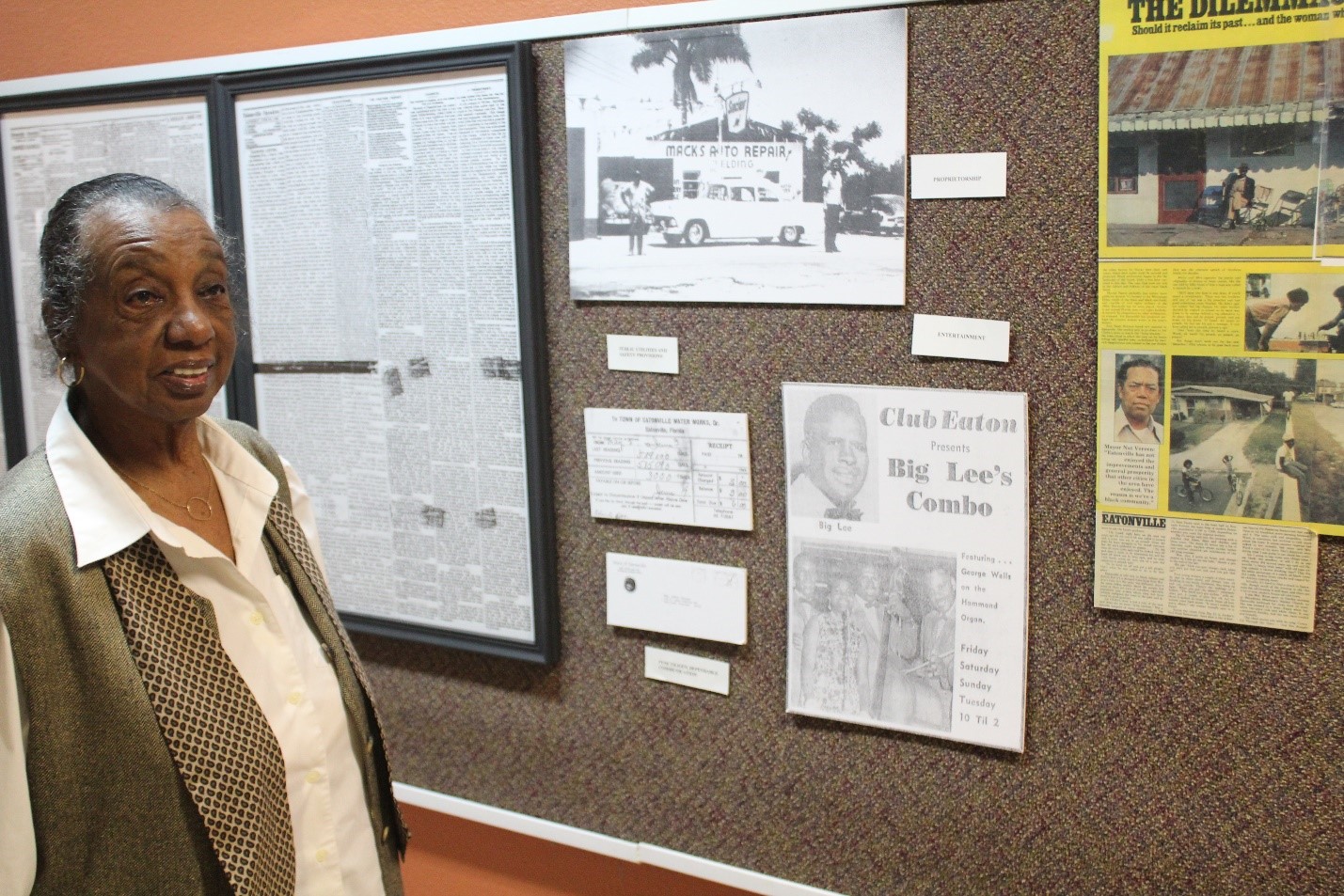

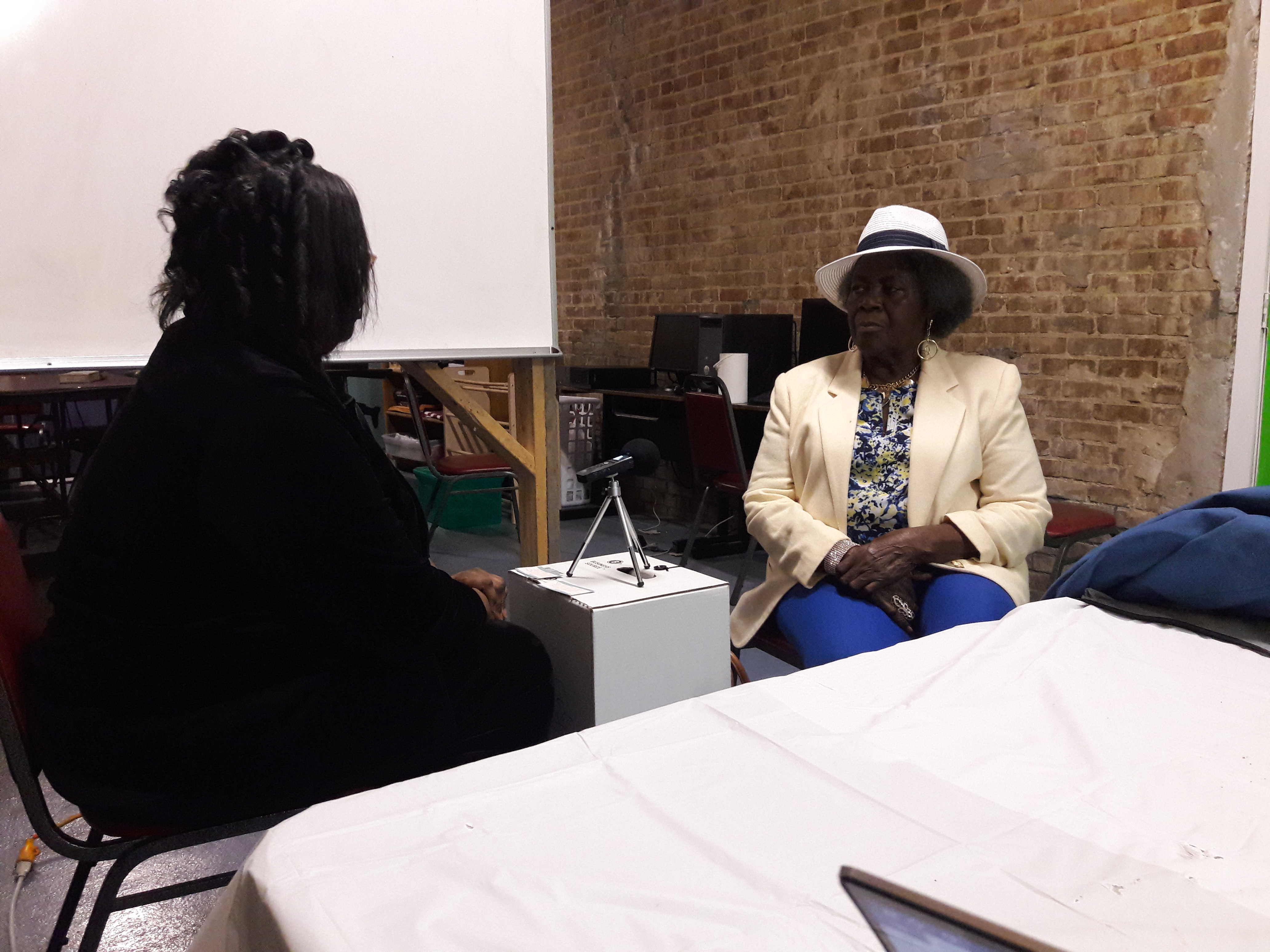

However, those who came to the workshops were some of the most dedicated people I have ever met. One woman, Enda Earl Moore, is the last surviving member of the court-mandated bi-racial planning commission. Mrs. Moore, pictured below sitting right, took part in an oral history training session that Chaitra facilitated as part of the larger Backpack training. In this activity, pairs of participants practiced interview questions and then the group gathered to talk about what went well, and what to improve.

Chaitra also led an imaginative description activity where one person described their childhood room and their partner drew it. This opened conversations about the language and detail used in archival descriptive work, perspective, and how this leads to access of information.

I led one section about born digital material and another on reading archival documents. We talked about consistent file names and using conventions to ensure that files are understandable by multiple parties, as well as raising awareness of LOCKSS, file migration, and format. The second section I led was reading archival documents, which Timla had asked for specifically. I worked with colleagues in Wilson Library to create an easy to follow set of guidelines that presented questions to “ask the documents.” Participants looked at photos and the minute books and “read” the document, answering questions about format, audience, and purpose. All the activities provoked important conversations about access, preservation, and ownership of narrative and voice.

It was an exhausting schedule, but I wouldn’t change it for anything. I was moved by the warm welcome, and by the first day I almost forgot that I had to fly back to NC. We were invited back immediately, and I was sad to leave this place. Shaw has a history full of turmoil, closed businesses and dilapidated homes dot the streets. But it’s impossible to walk away from this place and these people without feeling their infectious determination and wanting to stay and be a part of their work. The power of place is startling in this town. The materials and resources from the Community-Driven Archives are only a small portion of this overall project, but I’m so glad we get to be a part of this work.

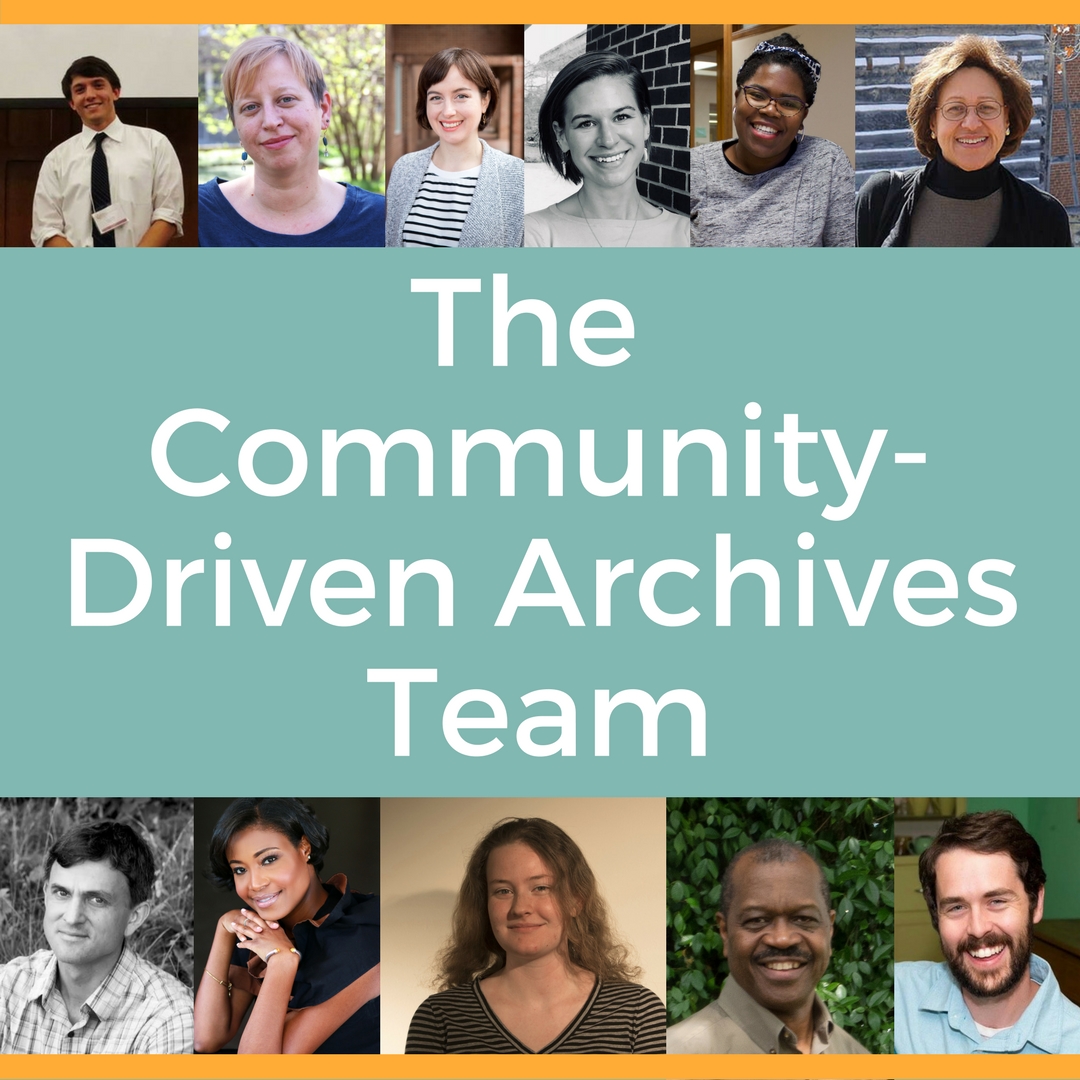

Contributed by Community Driven Archives Grant Research Assistant, Claire Du Laney