Between September 2020 and January 2021, I worked on an EBSCO-funded internship administered through the Association of Research Libraries focused on a Python text analysis project on oral history interview transcripts. I worked with the Community-Driven Archives team, which partnered with communities across the American South to amplify histories that have been silenced or marginalized in traditional archives. The purpose of this project was to explore the possibility of using computational methods on oral history data. I was interested in exploring how computational methods can build upon digitization, in which historical records are searchable on the web, to make community archives more accessible to their respective communities.

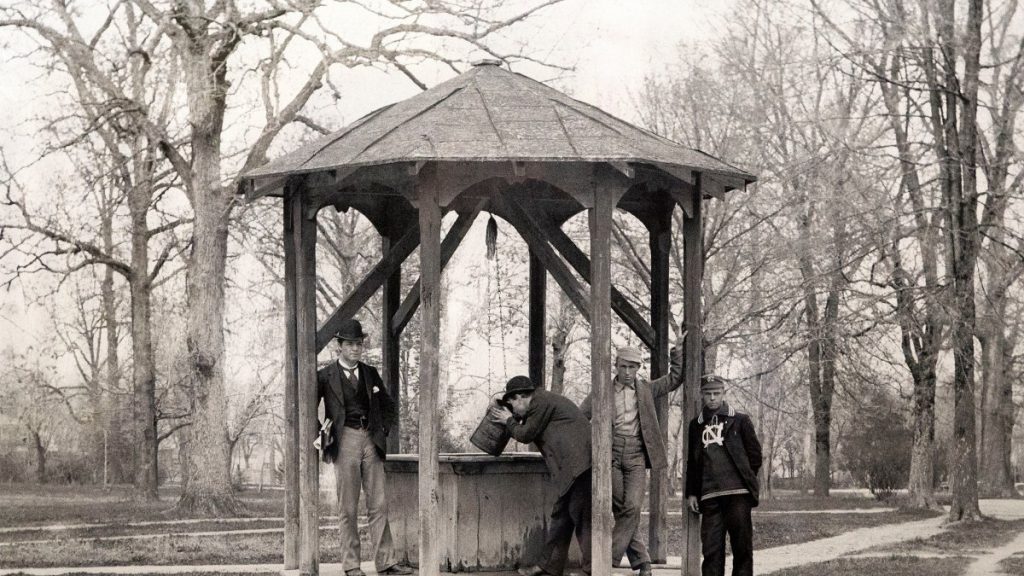

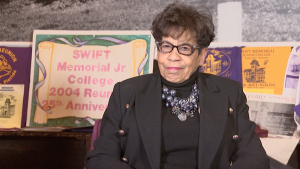

My project focused on oral histories created by the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project (EKAAMP), a public history and community archival project centered on the stories of Black former coal mining families in Eastern Kentucky. The Community-Driven Archives team collaborated with EKAAMP to support the creation of its collection, some of which is housed in the Southern Historical Collection at University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill, along with a series of traveling exhibitions. EKAAMP honors the place of Black Americans in Appalachia.

Learning Text Analysis in Python

Python is a powerful programming language. Aside from its extensive use in software and web development, Python is also widely used in computing and applying computational methods to humanities and social sciences data because of its powerful data modeling libraries and natural language processing algorithms. One such application is text analysis, where a body of textual data is processed and analyzed. When done well, text analysis can reveal patterns in topics and sentiments in large quantities of textual data.

I started this project being very new to the world of text analysis and to Python as a programming language. I used a variety of resources in my self-directed and explorative learning process, both on Python and on text analysis methodologies. Here are some of the resources that guided my project and helped me respond to challenges along the way:

- Your Guide to Latent Dirichlet Allocation: https://medium.com/@lettier/how-does-lda-work-ill-explain-using-emoji-108abf40fa7d

- How to Generate an LDA Topic Model for Text Analysis: https://medium.com/@yanlinc/how-to-build-a-lda-topic-model-using-from-text-601cdcbfd3a6

- Introduction to Latent Dirichlet Allocation: https://blog.echen.me/2011/08/22/introduction-to-latent-dirichlet-allocation/

I found the following text analysis projects and papers informative and relevant to this project:

- In Search of the Drowned in the World of the Saved: Mining and Anthologizing Oral History Interviews of Holocaust Survivors: https://dh2018.adho.org/en/in-search-of-the-drowned-in-the-words-of-the-saved-mining-and-anthologizing-oral-history-interviews-of-holocaust-survivors/

- A brief digital humanities discussion on analyzing oral history interviews from audio recording files: https://www2.fgw.vu.nl/werkbanken/dighum/data_analysis/text_analysis/ta-introduction.php

- Oral History and Linguistic Analysis: A Study in Digital and Contemporary European History: https://ep.liu.se/konferensartikel.aspx?series=ecp&issue=159&Article_No=2

I learned that most resources and available projects utilizing text analysis deal with bodies of text that are different than oral histories, both in content and structure. For instance, the conversational format of the interview transcripts meant that the more common text analysis techniques that are used on other kinds of texts will not yield meaningful results. Based on what I learned in my research, I explored two main text analysis methods, including Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), to categorize main topics discussed in the interviews.

My preliminary results yielded by the LDA methods aligned with the main topics covered in EKAAMP and Dr. Karida Brown’s research related to these histories. Some of the main topics that emerged in the text analysis results were: family reunions, school integration, and mining accidents.

Archives as Data: Computational Methods for Community Archives

In support of the larger work of the Community-Driven Archives project, I wanted to explore the research value of archival collections, such as oral history transcripts, as data that can be analyzed and visualized through computational methods. My goal was to gain deeper insight into these histories through text analysis, an automated process for gaining insight into a large collection of oral history interviews by mapping common topics and visualizing patterns in conversations. Such computational techniques would then be used to extract a variety of data about the collection as a whole and about individual interviews. This would support community researchers’ discovery and identification of these histories.

This model can then be built upon and implemented in the future for metadata generation for collections with similar size and scope. High quality metadata that provides descriptive information about an oral history collection not only facilitates better discovery and identification, but also creates exciting possibilities for presenting and analyzing the research data, such as data visualization of migration paths among Black former coal mining families represented in EKAAMP oral histories.

Perhaps this project can serve as an example of using computational tools and techniques for unlocking data and gaining insight into large oral history collections. Community leaders in charge of similar public history projects can use such tools to reimagine discovery, management, and description of their oral history archives.

I am in the final phases of developing a website to open source my code for the public to use and build upon. The website will include a brief collection description, as well as a brief discussion of challenges and snippets of Python code to run on an internet browser.

Data analysis methods and techniques can transform large quantities of non-machine-readable content, such as oral histories, into machine readable content. This transformation would enable community leaders to enhance their archives by creating robust research data sets for computational research. The new data would then allow community researchers to present, visualize, and analyze oral histories in new and dynamic ways.