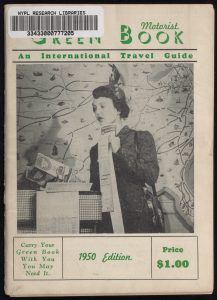

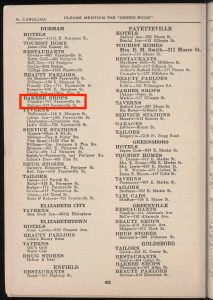

I grew up in North Carolina. While I recall eighth grade social studies classes focused on North Carolina history, I do not have many memories of learning about the numerous African American communities across the state until graduate school. Currently, I am writing a dissertation on North Carolina listings in The Negro Motorist Green Book (Green Book), a booklet published from 1936-1966 to assist African American travelers in avoiding encounters of racial discrimination. My research is not about the experience of African American travel. Rather, my work focuses on the people who assisted travelers seeking goods, services, and information. Who were the people who guided Green Book travelers through North Carolina?

Fayetteville Street was home to the main commercial and cultural strip in Hayti. DeLuxe Barbershop, along with many of Hayti’s important places, relocated due to the City of Durham’s Urban Renewal program. Many others were lost completely. In Hayti, urban renewal destroyed more than one hundred Black businesses.

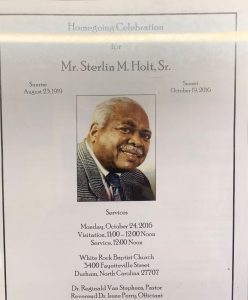

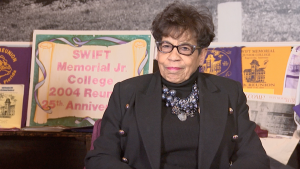

While general information about the DeLuxe Barbershop and other Green Book locations is available within libraries and archival collections, these records do not always reveal a business’s or the owner’s role within the larger community. Working directly with local residents and family descendants connected to Green Book proprietors helps to fill the gap. I had the opportunity to conduct an interview with Derrick Green, the current owner of the DeLuxe Barbershop and a close connection to Sterlin Holt, for my Archival Seedlings project. The recorded conversation not only puts into context the DeLuxe Barbershop’s role within the Hayti community, but it also illustrates the importance of community memory keepers passing down the stories of earlier generations and keeping local history in the forefront of public awareness.

Derrick Green met Sterlin Holt through Holt’s son in Mebane, North Carolina. After realizing a close family connection, Holt invited Green to work at the barber shop in Durham. In the interview, Green describes the relationship he had with Holt, who became his mentor. Green fondly recalls Holt as someone who was willing to help out a young person, sharing lessons as a barber on what it meant to be a public servant, and who would talk to you like a peer. Holt reminisced with Green, sharing memories of the Great Depression and the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. According to Green, the way Holt talked about the past felt as if history came in through the front door.

In addition to Holt’s lessons on being a barber, Green keeps the stories about Mr. Holt and the DeLuxe Barbershop’s history alive. Green shared how the barber shop received its name during the interview. The African American community in Durham had a national reputation, and many well-known individuals came through the area on their travels. According to Green, Sterlin Holt provided haircuts to famous individuals, from singer James Brown and civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr. to John Hope Franklin, a prominent African American historian. Early on, Holt determined that if he was going to provide a deluxe service to his customers, then the shop should be named DeLuxe Barbershop. Green emphasized that Holt also dressed the part of someone providing a deluxe service by coming to work every day in a suit and tie.

Derrick Green described the DeLuxe Barber Shop’s role within the community as “a Black man’s country club.” (3) As Green shared, one could find almost anything one needed at the barber shop simply due to the fact that everyone, from the lawyer to the police officer to the local store clerk, came through the shop. Additionally, Green, sharing community memories of Mr. Holt’s interactions with Durham’s youth, referred to the DeLuxe Barbershop as a place for children as well as adults. World Nursery School, located in the barbershop’s basement, was operated by Mr. Holt’s wife, Josie Holt, along with Mrs. Virginia Alston, Green’s grandmother. In this way, the DeLuxe Barber Shop was a community space for everyone, adult or child, resident or visitor.

Much of the current narrative about the Green Book revolves around the publication and first-hand accounts of African American travel during the Jim Crow era. My project with the Archival Seedlings program and my dissertation research examine the publication’s North Carolina listings to reframe the Green Book and Black travel within the social dynamics of local communities, an approach that would not be possible without working with family descendants of Green Book proprietors and community memory keepers. Derrick Green’s interview is one of several from my research that shifts the narrative about the Green Book from a travel guide to a publication highlighting social networks, community hubs, and prominent changemakers in African American communities across North Carolina.

Visit Community Knowledge in North Carolina: The Negro Motorist Green Book in the Old North State to hear the full interview with Derrick Green and to view images associated with the DeLuxe Barbershop.

(1) The 1951 Durham City Directory is the last edition to list both Holt and Lewis as co-owners of the barbershop. Holt is first listed as the sole owner in 1950 then again in 1952 and in subsequent years; DeLuxe Barbershop Founding Plaque (image), Community Knowledge in North Carolina: The Negro Motorist Green Book in the Old North State, communityknowledgenc.org, accessed December 1, 2020; 1947 Durham City Directory, p. 130 (alphabetical listing); 1948 Durham City Directory, p. 146 (alphabetical listing); 1949 Durham City Directory, p. 137 (alphabetical listing); 950 Durham City Directory, p. 121 (alphabetical listing); 1951 Durham City Directory, p. 124 (alphabetical listing); 1952 Durham City Directory, p. 124 (alphabetical listing).

(2) 1952 Durham City Directory, p. 124 (alphabetical listing); “Advertisement/Notice,” The Carolina Times, January 31, 1953, p. 8, North Carolina Newspapers/DigitalNC, digitalnc.org, accessed September 25, 2019; 1955 Durham City Directory, p. 159 (alphabetical listing); 1956 Durham City Directory, p. 154 (alphabetical listing); 1958 Durham City Directory, p. 165 (alphabetical listing); 1959 Durham City Directory, p. 161 (alphabetical listing); 1960 Durham City Directory, p. 170 (alphabetical listing); 1961 Durham City Directory, p. 177 (alphabetical listing); 1962 Durham City Directory, p. 180 (alphabetical listing); 1963 Durham City Directory, p. 177 (alphabetical listing); “Christmas Advertisement,” The Carolina Times, December 25, 1965, P. 5B (Image 15), North Carolina Newspapers/DigitalNC, digitalnc.org, accessed September 25, 2019; “Announcement: Herbin & Miss Long,” The Carolina Times, September 19, 1970, P. 10A (Image 10), North Carolina Newspapers/DigitalNC, digitalnc.org, accessed September 25, 2019.

(3) Derrick Green, interview with Lisa R. Withers, November 18, 2020, communityknowledgenc.org, accessed December 1, 2020.

Lisa R. Withers was a participant in UNC Libraries’ 2020-21 Archival Seedlings program. For more about Archival Seedlings on the Southern Sources blog:

Archival Seedlings: Resourcing Local Collaborators Across the American South

Archival Seedlings: Putting Our Values into Practice, the 2020 Edition

The Community-Driven Archives Project at UNC-Chapel Hill is supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Follow us on Twitter: @SoHistColl_1930 #CommunityDrivenArchives #CDAT #SHC

Throughout the harrowing challenges of 2020, our Community-Driven Archives Team has been in conversation with our

Throughout the harrowing challenges of 2020, our Community-Driven Archives Team has been in conversation with our