Oral histories provide us with a direct window to the past – interviews with people that provide not only historical context and information, but also personal details and stories. They show how history is not just a series of events, but the real lived experience of everyday people. Oral histories can be revelatory, sad, empowering, and even just plain funny. Giving people free reign to talk about their lives gives us the chance to examine the details – the facts that often get left behind. What I wanted to do was provide a method for visualizing a few of the stories that were told in the oral histories that the Community-Driven Archives team of the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill had the privilege of archiving throughout our time working with the Eastern Kentucky African American Migration Project (EKAAMP).

Throughout my time working with the EKAAMP oral history collection, I reviewed transcripts and read through the words of Black former coal mining communities from eastern Kentucky that Dr. Karida Brown collected in collaboration with EKAAMP members. I was consistently drawn to the stories of the women. Their experiences – their drive throughout the Second Great Migration and beyond; their stories of working, having fun, falling in love – reading about the lives of these women really was breathtaking. Their lives, even down to the most mundane moments, were so rich and full of warmth. I wanted to find a way to show their experiences in historical context, to show just how far so many of these women went in their lives during a time where so many things were stacked against them. That’s how I decided to start the “Always Will Be My Home” StoryMap project.

Selecting Stories

To start this project, I selected several stories from the oral history collection. I started by narrowing down the stories just to the women in the collection. Then, after a primary review of these interview transcripts, I pulled out the transcripts of the women who had moved away from the Kentucky area at some point in their lives, whether on their own or with their families.

Since I had chosen the Second Great Migration period as the timeframe for my project – a time period following the second World War in which many African American families moved from the American South to the Northeast, Midwest, and West – I was able to further narrow down the list of women to those who had made that journey. I had a pretty short list by this time, and I selected four amazing women whose stories ranged across many experiences – moving with their family for work, moving on their own but returning to Kentucky frequently throughout their lives, reuniting with community and family who had already moved, and more.

However, after selecting these stories, I felt I had limited the field. I wanted to show that Black women during these times led rich lives, but not all rich lives had to be contextualized by a move away from the South or by Southern culture and Black Southern experiences. Ultimately, I chose to add the story of a woman who moved to St. Louis, Missouri with her husband during the industrialization period.

Of course, I still feel sad that I couldn’t include the experiences of so many other women in the collection. But the purpose of this project was to highlight a few women’s stories and show the visual storytelling possibilities that oral history collections can provide.

Using StoryMaps

I had heard of and learned how to use ArcGIS’s mapping software before, but it didn’t provide me with a way to portray the stories and visuals that I wanted to add to the oral histories I had selected. Thankfully, Kimber Thomas, Postdoctoral Fellow at the University Libraries, showed me how a tool created by ArcGIS, StoryMaps, could be used to create a flowing story post using maps that could be created quickly and easily to illustrate the journeys of the selected oral history narrators.

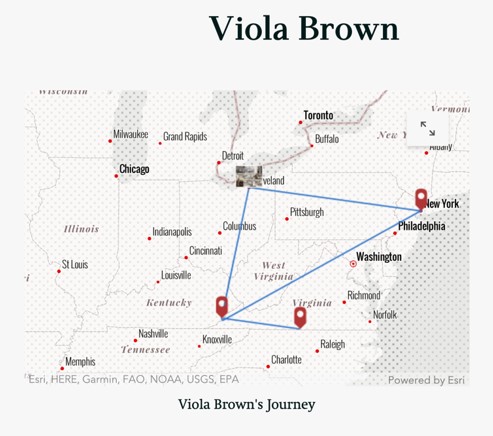

Entries can be created like the one featured above, to allow for a map to be seen alongside selected text. When a reader clicks into the map, each point in the map can have images, text, and links added in to give geographical, historical, and personal information based on each location.

Creating these maps is fairly intuitive – the tool gives you a short tutorial, and everything can be customized – from the color of the lines and pins, to the type of map itself. And StoryMaps even provides examples of other stories that have been created using the tool to give you ideas. Videos, text posts, slideshows, and images or other visualizations can also be embedded throughout the story. Of course, more detailed or complicated map visualizations created in ArcGIS can also be embedded and are even more interactive or illustrative. But the ease of using the simpler maps for this project suited me and my needs well!

Research

Part of the experience of working on this project was research – I wanted to add historical context to many of the stories I was gathering. My sources ranged from other historical collections in libraries and universities, as well as books written about the Second Great Migration and Black communities in the United States. So many of the oral history subjects had their lives coincide with major social movements and events. Hearing about how people lived their lives during these huge events, lived them like it was just any other day, helps to contextualize life today. It’s hard to recognize in the moment, when you’re a young person going through daily life, that what you’re living through is going to change the course of history.

For example, one of the subjects, Yvonne McCaskill, marched with civil rights activist Father James Groppi, who worked to desegregate schools in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. For her, this was just an action she took as a young girl. She understood the importance of the event at the time because it was important to her and to her community – this was an event she had to join for her rights, not one she believed would become historically important. The urgency of this event in the moment was extremely personal. Seeing the personal side of history is just one of the things that working with oral history can really show people.

Reflection

Though my project changed many times and went through many iterations throughout the past year, I was ultimately able to do what I set out to do – to help people see and learn about the larger context of a few of the amazing stories available in the EKAAMP oral history collection. These story maps, together, create a narrative that underscores the connection of history and humanity. They are just one way to explore how oral histories can be used to guide people through the lives of others. Oral histories don’t just share context, but also perspective, joy, and depth.

In January 2020, Archival Seedlings emerged as the final initiative of the

In January 2020, Archival Seedlings emerged as the final initiative of the