The UNC campus is no stranger to controversial art. The Confederate Monument known as “Silent Sam” has a long history of causing controversy. It was erected in 1913 to honor the university students that fought to defend the south in the Civil War. The “Unsung Founders Memorial,” a memorial to the unrecognized African American slaves and laborers who helped build the university, was designed as a counterpoint to “Silent Sam.” Yet it too has garnered its own amount of criticism. Considering the nature of public art as public, it is to be expected that this form of art will spark debate.

In October 1990, the sculpture “The Student Body,” by artist Julia Balk, was installed in front of Davis Library. Almost immediately some UNC students expressed disapproval of some of the statues, which they believed promoted racial and gender stereotypes. The work consisted of a group of seven bronze figures, including an African American male figure twirling a basketball on his finger, an African American woman balancing a book on her head, an Asian American women carrying a violin, and a white woman holding and apple and leaning on her male companion’s shoulder.

The Daily Tar Heel, Black Ink, and the Chancellor’s office received hundreds of letters regarding the perceived racist and sexist overtones of the sculpture. Students, faculty and even the larger community got involved in the heated discussion. The debate even gained national attention, appearing in a New York Times article.

Some groups, like the Minority Caucus and the newly formed Community Against Offensive Statues, demanded the sculpture be moved to a less prominent location. Others wrote in defense of the sculpture and cited the oversensitivity of the offended parties as the problem, not the art. Although opponents of the sculpture acknowledged that the artist meant no harm, they still viewed the work as inappropriate. In a four page letter found in Chancellor Hardin’s files, the artist, Julia Balk, explains and defends her conception of the statues:

As its creator, I cannot help but respond to the debate that has arisen over my sculpture, “The Student Body.” Although I believe a work of art should speak for itself, in this case, unfortunately, my voice is not being heard. Nor is my sculpture being seen for what it is—seven students co-existing in a harmonious group [. . . .]

I would like to take this opportunity to discuss the four figures which have been the focal point of discussion. First, the basketball player [. . . .] The figure is rendered as an African American because it has been made with reverence for the talent of an extraordinary athlete. It is neither racist nor stereotypical. If I had made him a white male, I might just as easily have been criticized for ignoring the contribution made by African American Athletes to the University [. . . .]

(Letter by Julia Balk, from the Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Paul Hardin Records #40025 University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

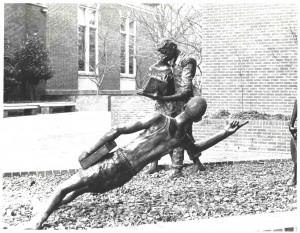

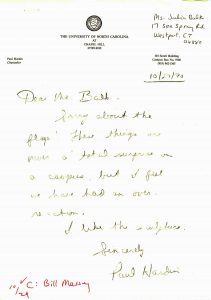

Over the course of this dispute, the statues were repeatedly vandalized. At one point the figure of the basketball player was knocked over and the basketball was stolen. The picture above, which is from a recently acquired, unprocessed collection of photographs from Black Ink magazine, shows the sculpture in that compromised state. Another act of vandalism was acknowledged by Chancellor Hardin in a letter to Balk for which he apologizes and refers to the debacle as “an over-reaction.”

Shortly after the incident, university officials elected to repair the basketball player and it was decided that the sculpture would be moved from out in front of Davis Library to a spot behind Hamilton Hall. At a later date, the basketball player and the figure with the violin were removed without any explanation.

Time to set the record straight about the sculpture I was commissioned to design and create for UNC. Unfortunately, I was not privy, prior to building this monument, to the unfortunate racial tensions which have caused so much unnecessary uncivil behavior amongst the student body.

This sculpture was dedicated to the honorable Michael Jordan, a UNC alumni. The fact that the sculpture I designed with reverence and admiration for this extraordinary athlete was not respected. This sculpture has been broken time and time again. Now it has disappeared. Shame on the vandals who perpetrated such a a heinous crime, not only against art but, most importantly, against humanity.

As many of you may know, UNC was originally built by former African slaves. The traffic cones that were placed on the heads of the seven sculpted figures I created were

a mocking testimonial to the presence of the KKK on Campus.

It’s time for a change.

We are all brothers and sisters.

Bless us all