While national prohibition was voted into law in 1919 with the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, North Carolina had been dry since it passed a state-wide prohibition law in 1908. As the sale and consumption of alcohol in North Carolina had already been banned for twelve years when enforcement of the 18th Amendment began in 1920, prohibition had little direct effect on the University.

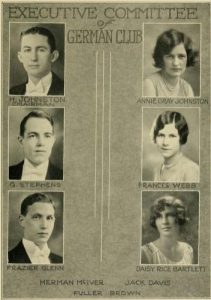

However, a 1925 German Club dance held around Thanksgiving prompted a harsh response from President H.W. Chase. Despite its name, the German Club was not related to the nation of Germany or the German language. Rather, the club, organized in the late nineteenth century, planned formal dances and other social events for its members. A ‘German’ was a kind of social dancing that became popular following the Civil War.

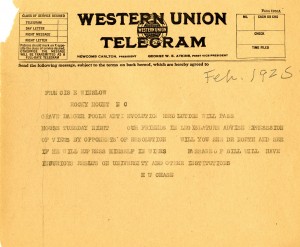

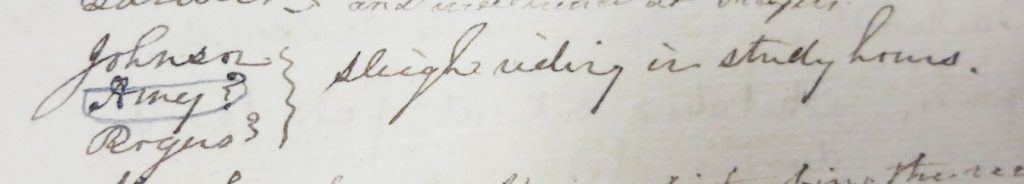

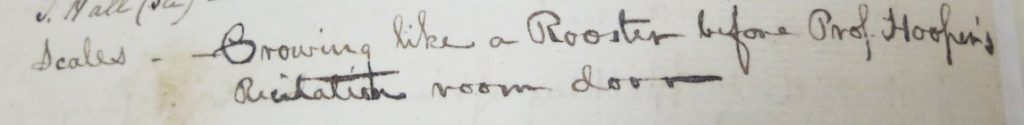

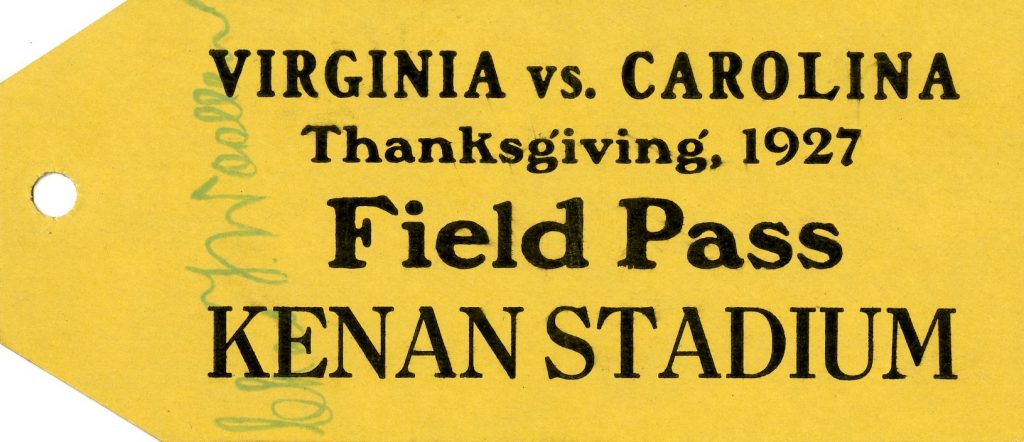

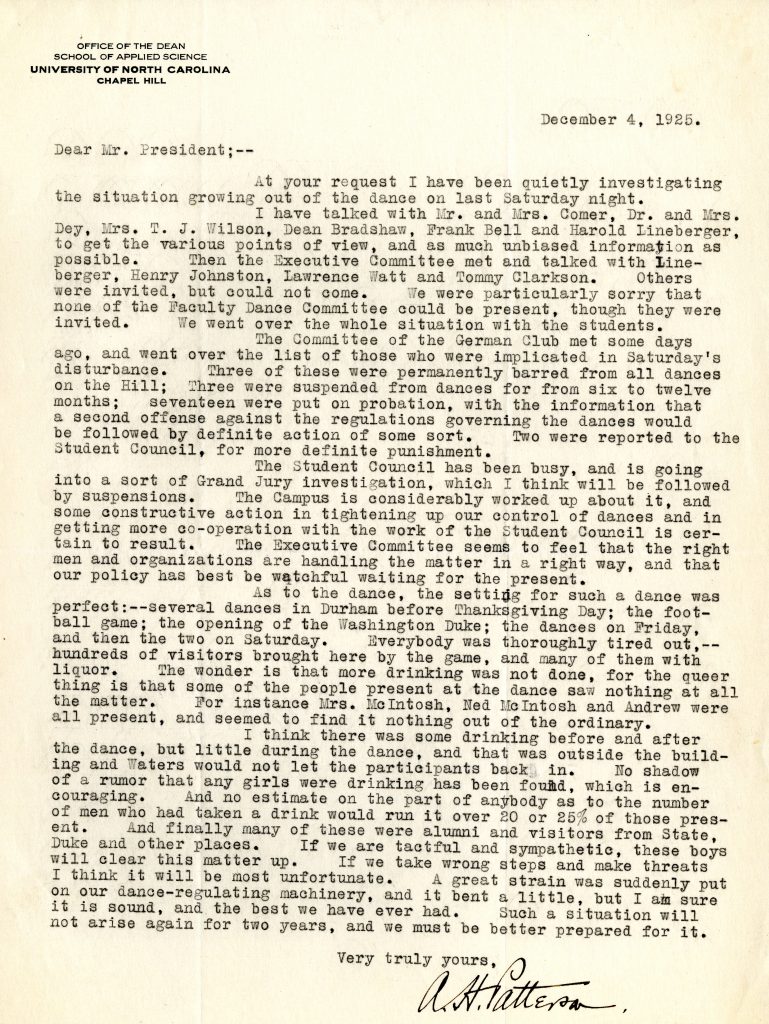

The incident caused by this dance was investigated by Andrew Henry Patterson, a professor of physics and Dean of the School of Applied Sciences. In his report to President Chase, Patterson noted that the conditions for illegal drinking were perfect as there were, “hundreds of visitors brought here by the game, and many of them with liquor. The wonder is that more drinking was not done[….]” The game to which Patterson referred was the annual Thanksgiving Day game against the University of Virginia. According to Patterson, “no estimate on the part of anybody as to the number of men who had taken a drink would run over 20 or 25% of those present,” and that “no shadow of a rumor that any girls were drinking has been found, which is encouraging.”

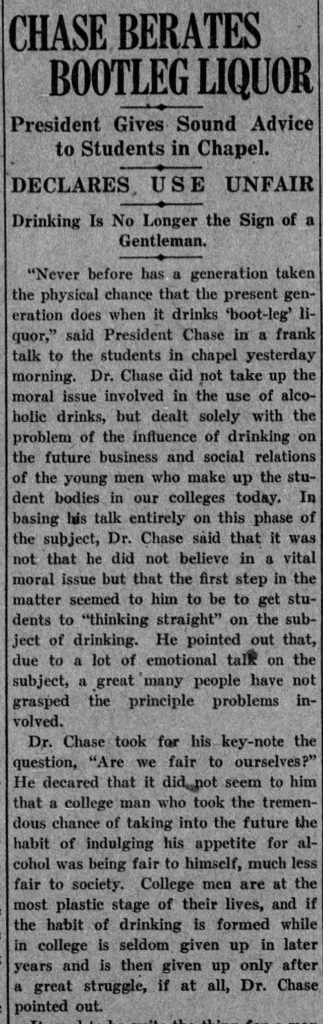

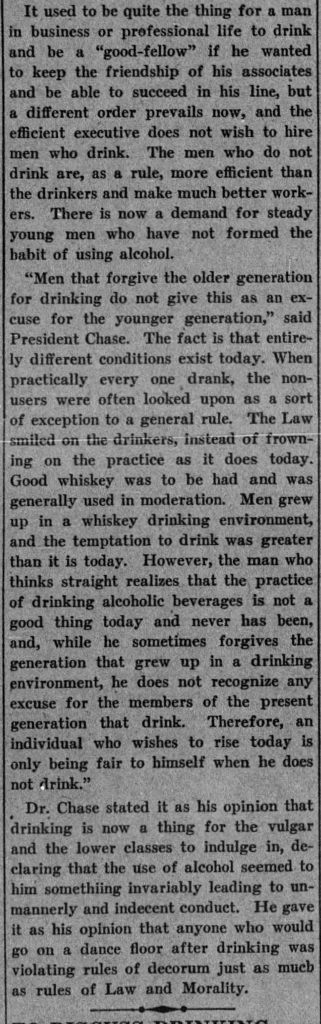

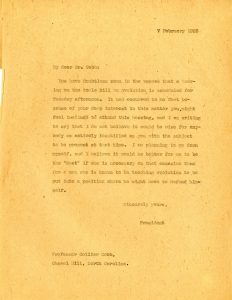

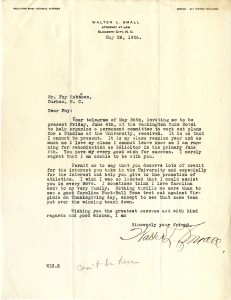

On the day this letter was sent to President Chase, December 4, 1925, he delivered an address to students in chapel discouraging the use of alcohol. Chase emphasized “the problem of the influence of drinking on the future business and social relations of the young men who make up the student bodies in our colleges today.” He went on to state “his opinion that drinking is now a thing for the vulgar and lower classes to indulge in” and that alcohol use was something “invariably leading to unmannerly and indecent conduct.”

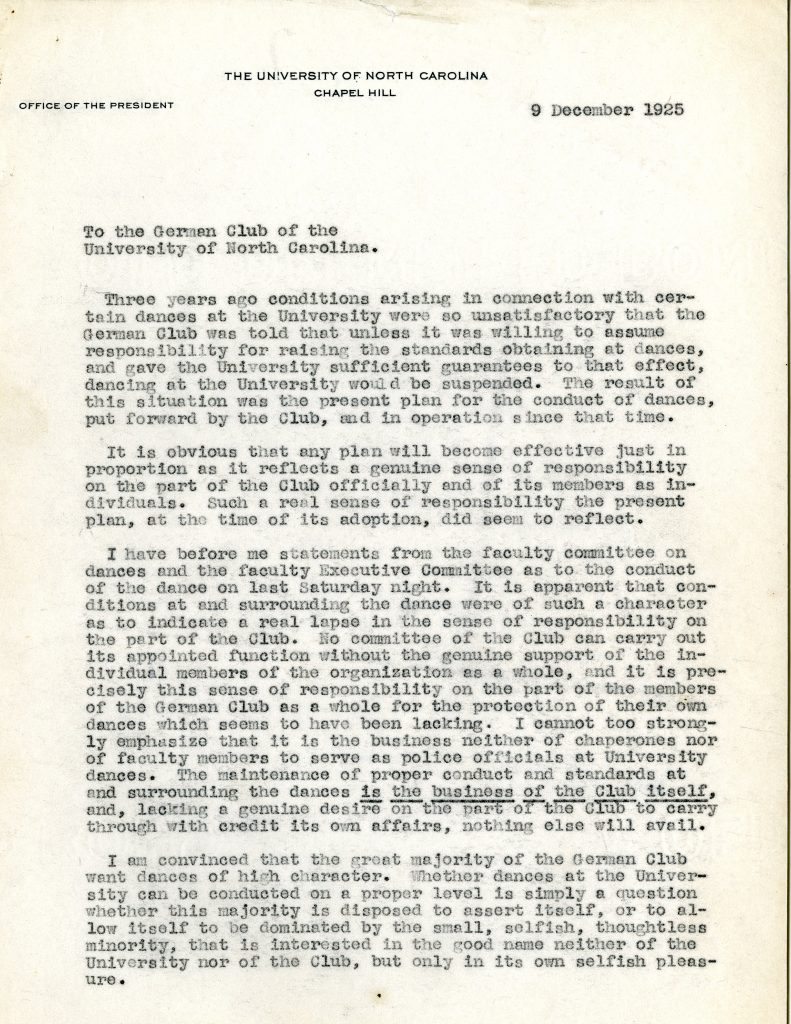

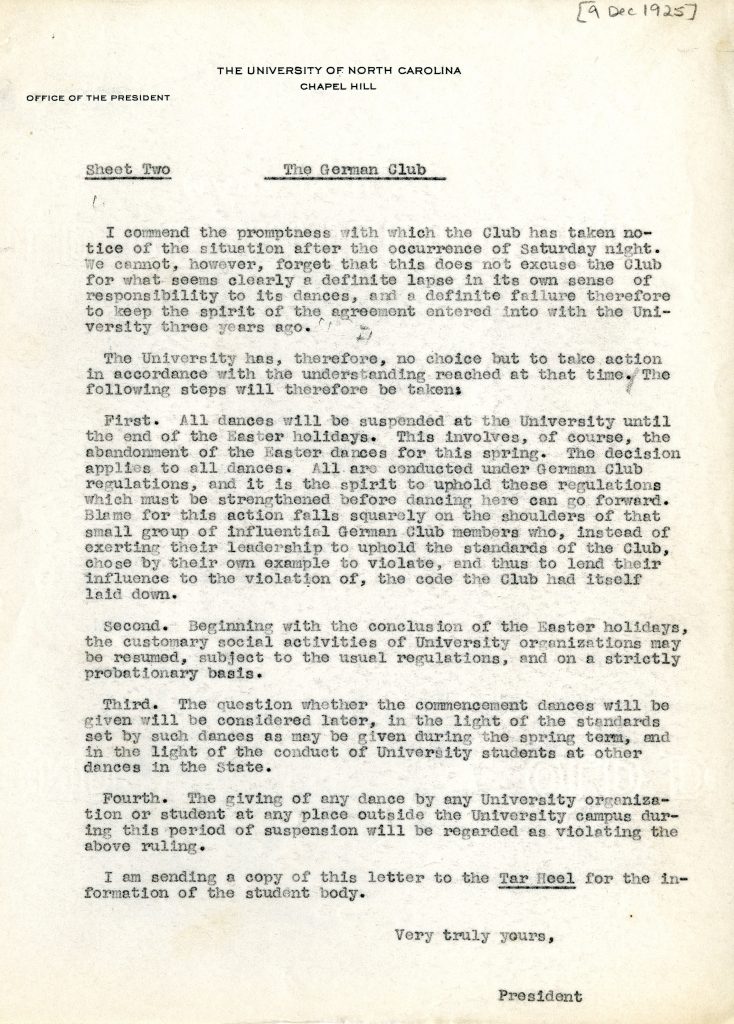

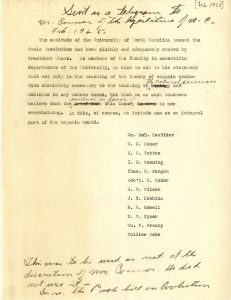

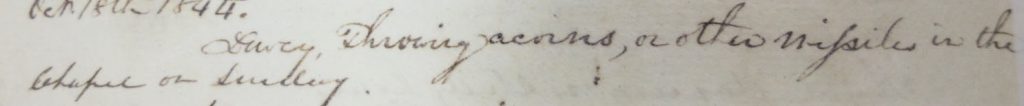

This incident and its investigation prompted President Chase to suspend all dances at the University until the end of Easter holidays. This suspension also extended to “the giving of any dance by any University organization or student at any place outside the University campus.” When the suspension ended in April of 1926, the German Club adopted new bylaws that made its executive committee responsible to the University for the conduct at all dances, regardless of the clubs or groups hosting them. According to the Daily Tar Heel on April 15, 1926, these bylaws also imposed regulations on dances. These included no smoking on the dance floor, no girls leaving the dance hall without a chaperone, and strict end times for dances. Most dances were required to end by 1:00 AM, while Saturday night dances had to end by midnight. Some German Club dances were permitted to last until 2:00 AM. The German Club continued to organize dances and concerts until the late 1960s.

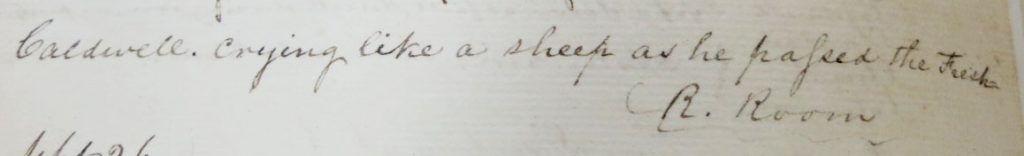

[President Chase’s letter to the German Club suspending all dances, from the University of North Carolina Papers (#40005), University Archives]