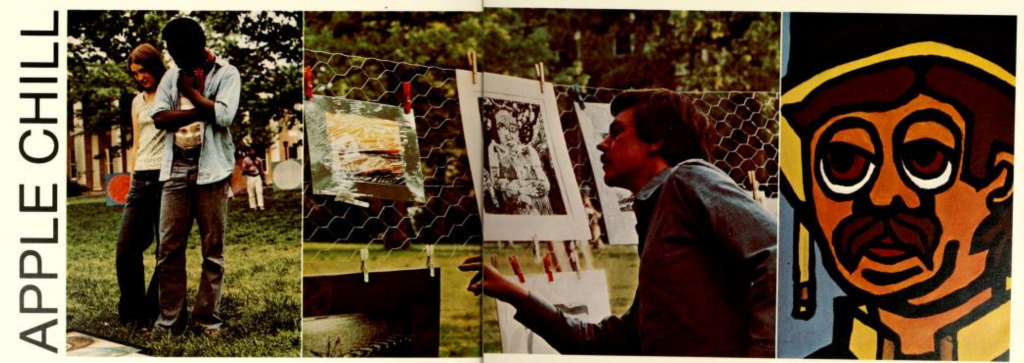

There are many forms of protest and one of them is the uninhibited celebration of your culture and the artistic achievements of your peers. Last month at the Project STAND (Student Activism Now Documented) symposium in Atlanta, one of the student panelists emphasized the necessity for uplifting depictions of black joy in addition to recognizing some of the struggles of activism. The Black Arts Festival, held by the Black Student Movement from 1972 to 1981, is an example of such joy.

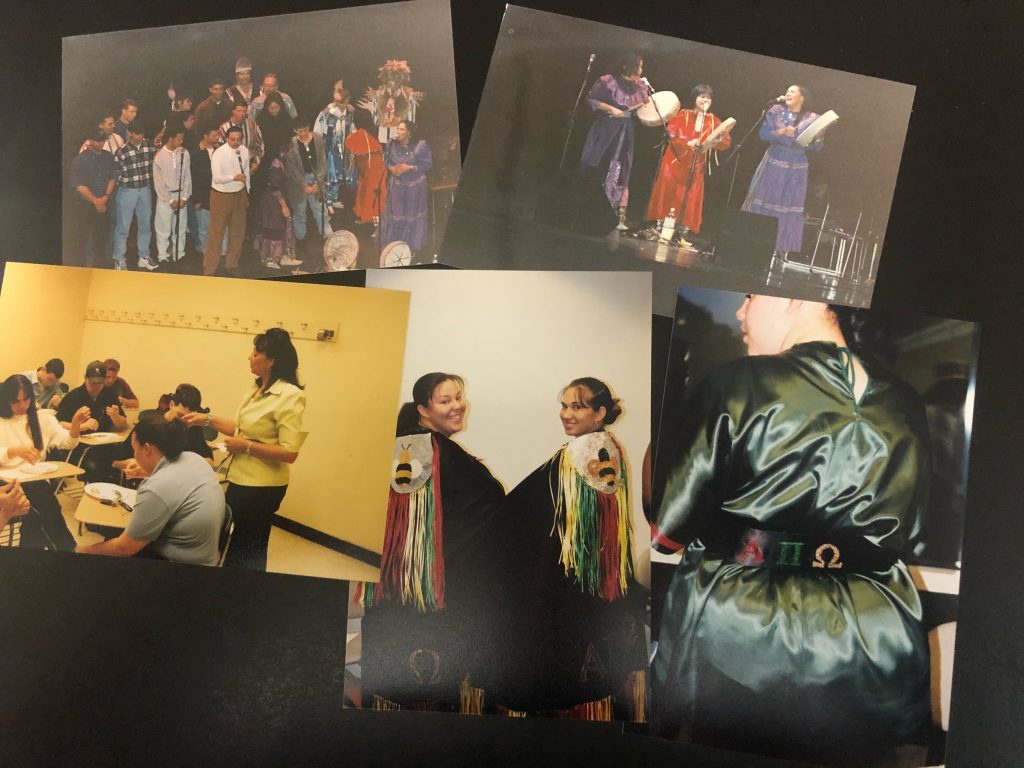

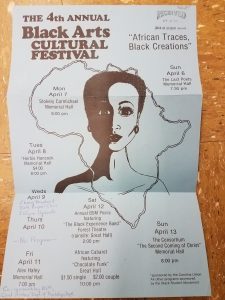

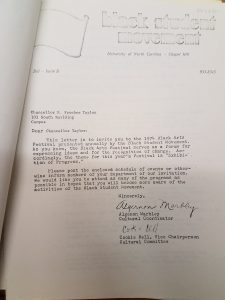

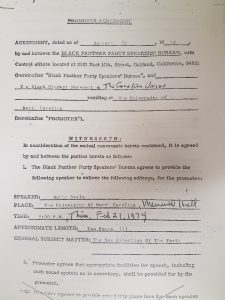

The relationships and roots of Black American art in the African diaspora were consistent themes in the 1973 festival. While performance seems to be the dominant form of expression in each year’s festival, the week-long series of events also featured panel discussions and classes. The festival in 1973 included a conversation between Chapel Hill’s first black mayor, Howard Lee, and activist Owusu Saudaki (Mills, 1973). Often, the BSM reached out to communities near UNC and workshops were taught by Durham’s Ebony Dance Theatre and the Bowie State Dancers (Starr, 1979).

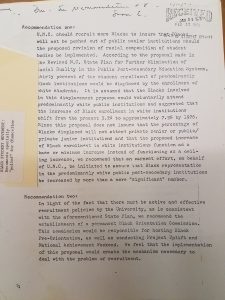

In 1975, students expressed concern for continuing the festival, and conversations were had about how a black student organization on a predominantly while campus could thrive in terms of funding and administrative support. The festival was put on hiatus between 1976 and 1978, during which time the organization focused on other concerns like recruitment of black faculty and students (Carolina Union Records).

In 1980, the festival saw much less of an audience outside of the 300 audience members who came to support the Freshman Bloc, a skit-based variety show. The festival continued in 1981, with Wanda Montgomery as Cultural Coordinator. (Blossom, 1981). This is seemingly the last year, because in 1982, the BSM continued to fight for funding. The Black Arts Festival was under scrutiny, funding was cut and some of the events were added to Black History Month (Black Ink, 1982).

There are some occurrences of week-long events similar to the Black Arts festival after this. In 1991, an African American culture week called “African Americans in the Arts,” sponsored by the Black Cultural Centers Special Programming Committee, featured the Opeyo! Dancers (Mankowski, 1991). In the early 1990s, African American Culture Week is still mentioned in Black Ink. The Black Student Movement and its subgroups continue to produce, sponsor and curate performances, continuing their legacy as an organization that uplifts black joy.

References:

Black Student Movement in the Carolina Union of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40128, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Blossom, Teresa (1981). “BSM Black Arts Festival Arrives Mar 18-25”. Black Ink. Retrieved from

http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/2015236558/1981-03-17/ed-1/seq-3/

Mankowski, Melissa (1991). “Opeyo! Dancers Mix Modern with Traditional Steps”. The Daily Tar Heel. Retrieved from http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1991-09-27/ed-1/seq-5/

Marbley, Algenon. (1973). “BACF Affect Apathy”. The Black Ink. Retrieved from http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/2015236558/1973-04-01/ed-1/seq-4/

Mills, Janice. (1973). “Realm of Black Arts Explored”. The Black Ink. Retrieved from http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/2015236558/1973-04-01/ed-1/seq-4/

Starr, Mary Beth. (1979). “Notable Groups Reflect Culture in Performance”. The Daily Tar Heel. Retrieved from http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1979-03-23/ed-1/seq-12/

Williams, Linda (1974). “’74 Festival Set” Black Ink. Retrieved from http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/2015236558/1974-03-01/ed-1/seq-1/

Worsley, Carolyn. (1979). “A Week of Arts, Entertainment.” The Daily Tar Heel. Retrieved from

http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1979-03-23/ed-1/seq-12/

Unknown Contributor. (1982). “Choir Guilty as Charged” Black Ink. Retrieved from http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/2015236558/1982-04-29/ed-1/seq-2/