From April 2-4 of 1976, the Carolina Gay Association (CGA) hosted the first annual Southeastern Gay Conference, a conference dedicated to “furthering the feminist and gay movements.” Tom Carr, the CGA Conference Coordinator, called it “a celebration of the gay lifestyle.” A major theme of the conference was how the gay identity, whether open or hidden, influences society, and that theme was addressed by three out of four of the major spokespersons.

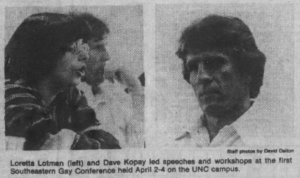

The three spokespeople in question were Dave Kopay, Loretta Lotman, and Perry Deane Young. Dave Kopay was a running back for the Washington Redskins and one of the first professional football players to come out as gay (in December 1975). The Daily Tar Heel reports that in a press conference, Kopay said:

The three spokespeople in question were Dave Kopay, Loretta Lotman, and Perry Deane Young. Dave Kopay was a running back for the Washington Redskins and one of the first professional football players to come out as gay (in December 1975). The Daily Tar Heel reports that in a press conference, Kopay said:

Many athletes are trapped by the feeling of macho heaped on the male in the U.S. To be homosexual and an athlete in unheard of. Hopefully there will be more athletes to come out now.

Young was a former writer for the Durham Morning Herald who was collaborating with Kopay on a book about homosexuality.

Lotman was the media director for the National Gay Task Force, a videotape producer, and additionally founded G-MAN, the Gay Media Alert Network. In her panel she discussed the discrimination faced by lesbians in the workplace and how they dealt with both sexism and homophobia.

The convention’s keynote address was delivered by Franklin Kameny, “the first self-acknowledged homosexual to run for Congress.” Though unsuccessful, he was nonetheless a man described by The Daily Tar Heel as “the country’s leading gay activist.” At the time the article was written, two gay congresspeople had won their seats since Kameny’s campaign. In his address Kameny stated that his campaign, even though it didn’t end with him in Congress, was beneficial to the gay community, partially because of its impact on the government’s political structure and partially as an effort to shift how queer culture was perceived by the minds of the general populace.

Read more about the Carolina Gay Association here.

References: