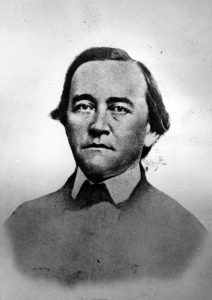

In the autumn of 1851, William Waightstill Avery had it all. The grandson of Waightstill Avery, a member of the committee that chose the site of the University, W.W. Avery had been elected to the North Carolina General Assembly, was a member of Carolina’s Board of Trustees, and was married to the governor’s daughter. The year before, W.W. Avery had been the keynote speaker at UNC’s graduation, where, only 13 years prior, he had graduated as valedictorian. However, in October of 1851, Avery’s life took a very violent and bizarre turn.

Avery’s nemesis in the General Assembly, Samuel Flemming of Burnesville, North Carolina, in Yancey County, was in a court battle with the family of his deceased wife, for her possessions. Avery, one of the most talented lawyers in western North Carolina, was representing Flemming’s opponents in court. On October 21, Avery viciously attacked Flemming’s character, calling his entire life’s work a “fraud.” Enraged, Flemming left the courthouse to buy a cowhide whip. When Avery left the courthouse, Flemming and the whip met him. Flemming brutally beat Avery, who was too small to fight back. The beating left Avery bloodied and weak but, more importantly, hungry for revenge.

Just a few weeks later, on November 11, Avery and Flemming crossed paths in a courtroom again, this time in Morganton, North Carolina. Flemming had business with the clerk and Avery had a number of clients appearing in court that afternoon. As they entered the court, Flemming shouted insults at Avery, who pretended not to hear them. However, just a few minutes later, as Flemming was finishing his business in the courtroom, Avery stood up and shot and killed Flemming, right in front of the judge.

Avery immediately surrendered himself to the sheriff and his trial began that Saturday. His attorney, John Bynum, claimed that Avery had been so provoked that the only just action was for him to kill Samuel Flemming. In a rhetorical flourish, Bynum said “no doubt, God forgives Mr. Avery. And whom God pardons, men dare not punish.” Exactly a week after Avery shot Flemming, Judge Battle, who had witnessed Avery shoot Flemming from his bench, read the jury’s verdict: “not guilty by reason of emotional insanity.”

After this bizarre encounter, Avery returned to the General Assembly and lived peacefully until 1864, when union sympathizers killed him. In 1958, the recently completed residence hall on Ridge Road was named in honor of William Waightstill Avery to commemorate his contributions to the university as an outstanding student and member of the Board of Trustees.