Community archives and other community-centric history, heritage, and memory projects work to empower communities to tell, protect, and share their histories on their terms. In 2017, the Southern Historical Collection at the Wilson Special Collections Library of the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill was generously funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation with a grant to “form meaningful, mutually supportive partnerships that provide communities with the tools and resources to safeguard and represent their own histories.”

We argue that “community archive models and community-driven archival practice address the ‘symbolic annihilation’ of historically marginalized groups in the historical record, and aim to create sustainable and accessible memory projects that address these archival absences.”[1]

So what does it mean? A whole host of complex, complicated moving parts that, if done right, could help transform the historical record! And it won’t just be the grant-funded Community-Driven Archives team (CDAT) doing it, but rather a true collaboration between the CDAT and its community partners to keep communities in control of their narratives.

Preserving Community History

Communities can preserve their history in a myriad of ways. They can keep records in brick and mortar buildings like the Mayme A. Clayton Library and Museum, or they can curate a digital archive like the South Asian American Digital Archive.[2] Communal heritage or memory can be expressed through historic markers or murals, like the Portland Street Art Alliance’s “Keep on the Sunnyside Mural Project”[3] and through guided walking tours, such as those created by the Marian Cheek Jackson Center.[4] History and heritage can even be expressed through parades, commemorations, and community celebrations. In her article, “The records of memory, the archives of identity: Celebrations, texts and archival sensibilities,” Jeannette A. Bastian notes,

the relationships between collective memory, records, community and identity as expressed through a particular celebration—a carnival— [is] located within the paradigm of a cultural archive. That paradigm theorizes that if an annual celebration can be considered as a longitudinal and complex cultural community expression, then it also can be seen dynamically as a living archive where the many events within the celebration constitute the numerous records comprising this expression.[5]

Working in Partnership

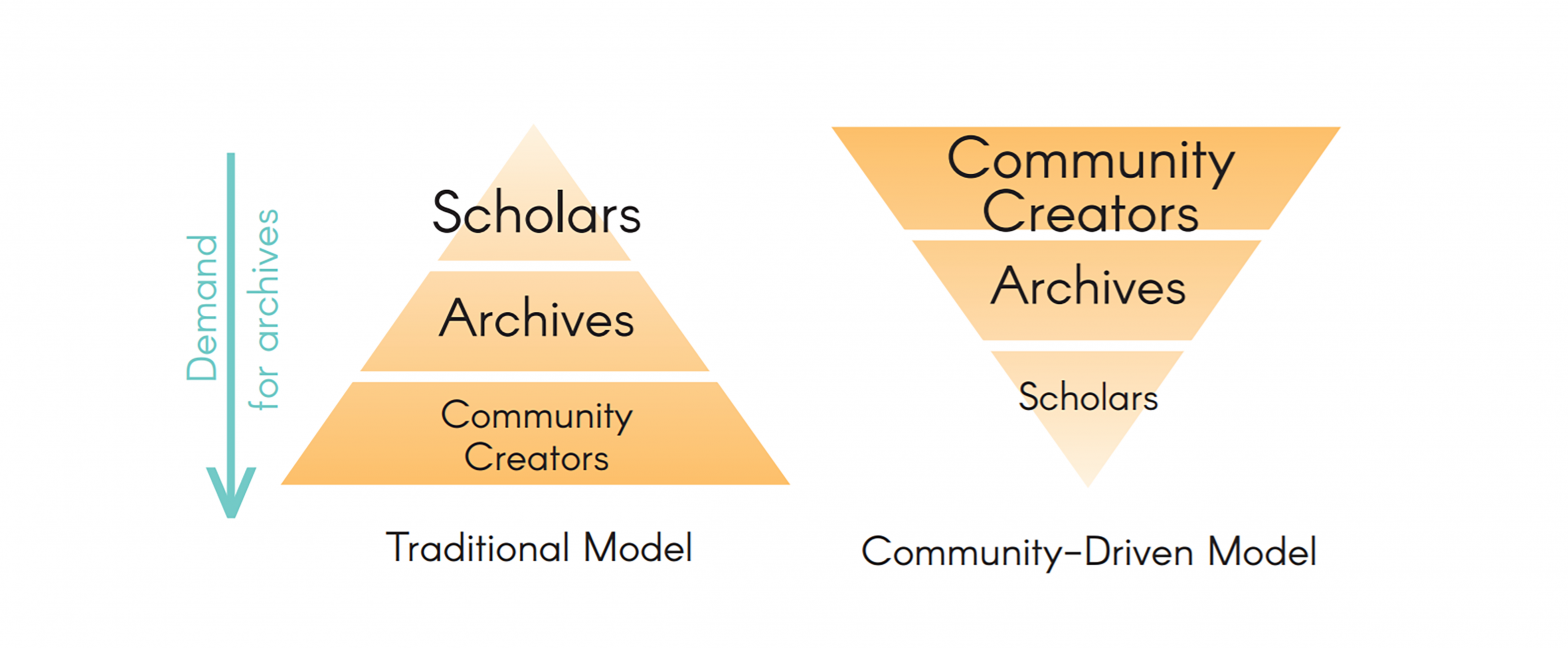

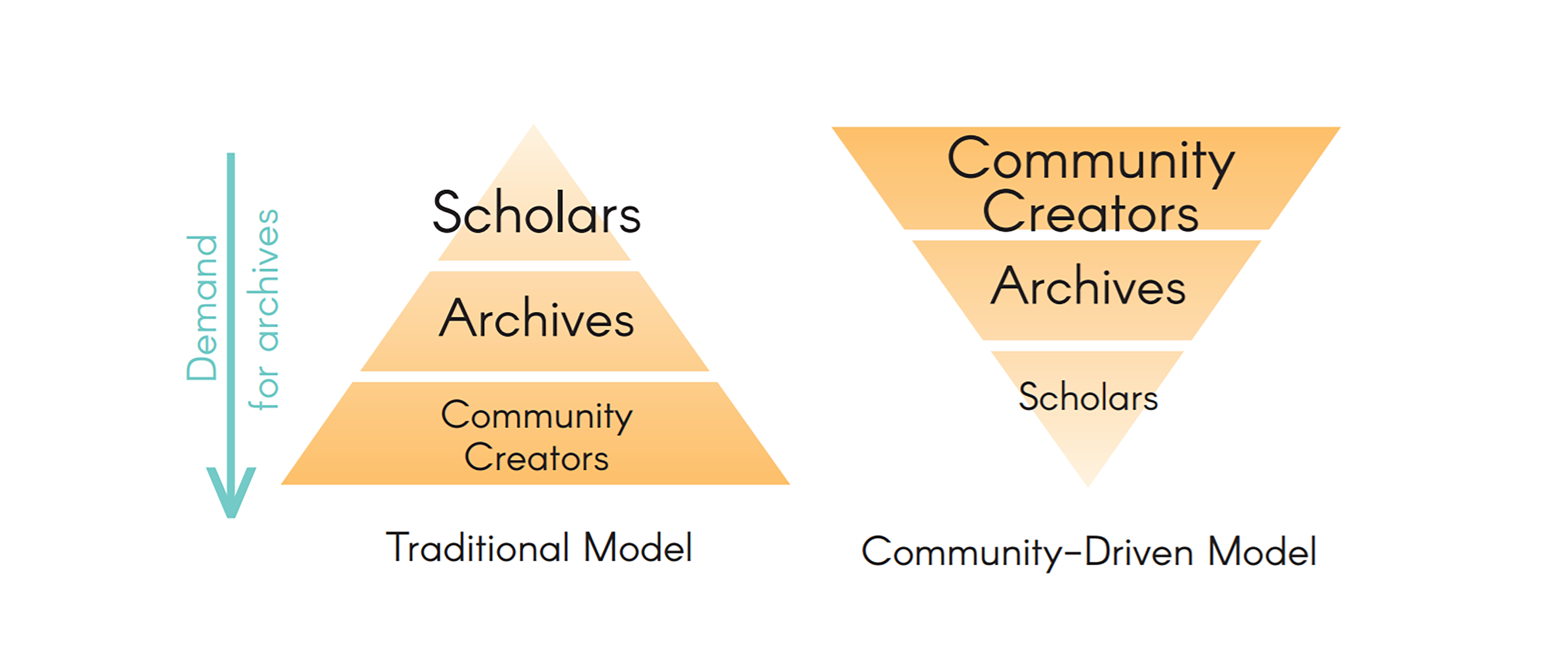

Community-archival work can also be done in public libraries like the Queens Memory Project or with the support of universities like our Community-Driven Archives project. We call our work “community-driven archiving” because we take cues from community members on the best ways to support their memory work, and we do not want to trample the long-standing tradition of community-owned-and-operated archives by co-opting their name.

We understand that working with communities to create archival, historical and heritage-based projects means grappling with complex issues of identity, ownership, and legacies of marginalization. Community history has always been present; the community archives movement didn’t suddenly discover these histories.[6] We have a lot more to share about our perspectives and experiences with community-driven archival work, including its benefits and challenges for a large organization with a complex history like the University Libraries at UNC-Chapel Hill. Boosting community voices in all their intersectional, diverse, complicated, and creative outputs is a top priority in the Southern Historical Collection these days.

- Michelle Caswell, Alda Allina Migoni, Noah Ceraci, and Marika Cifor, “‘To Be Able to Imagine Otherwise’: community archives and the importance of representation,” Archives and Records, 38., no. 1, (2017), 5-26.

- South Asian American Digital Archive, “SAADA,” https://www.saada.org/.

- Portland Street Art Alliance, “Keep on the Sunnyside Mural Project”, http://www.pdxstreetart.org/articles-all/sunnyside-mural-project.

- Marian Cheek Jackson Center “Soundwalk of Northside,” https://jacksoncenter.info/northside-stories/soundwalk-of-northside/.

- Jeannette A. Bastian, “The records of memory, the archives of identity: Celebrations, texts and archival sensibilities,” Archival Science, (2012), 122.

- Yusef Omowale, “We Already Here,” Medium: Sustainable Future, September 3, 2018, https://medium.com/community-archives/we-already-are-52438b863e31.