This post contains information about reproductive health that may be sensitive for some readers.

A decade of change in UNC’s student population sparked several changes in reproductive and sexual health dialogue on campus. From 1967 to 1977, women grew from 28.7% of the student body to 49.2%. Women were first allowed to enroll as freshman in most programs at the University in the early 1960s, and were admitted based on a higher academic standard until Title IX in 1972 (OIRA Fact Book, 1994).

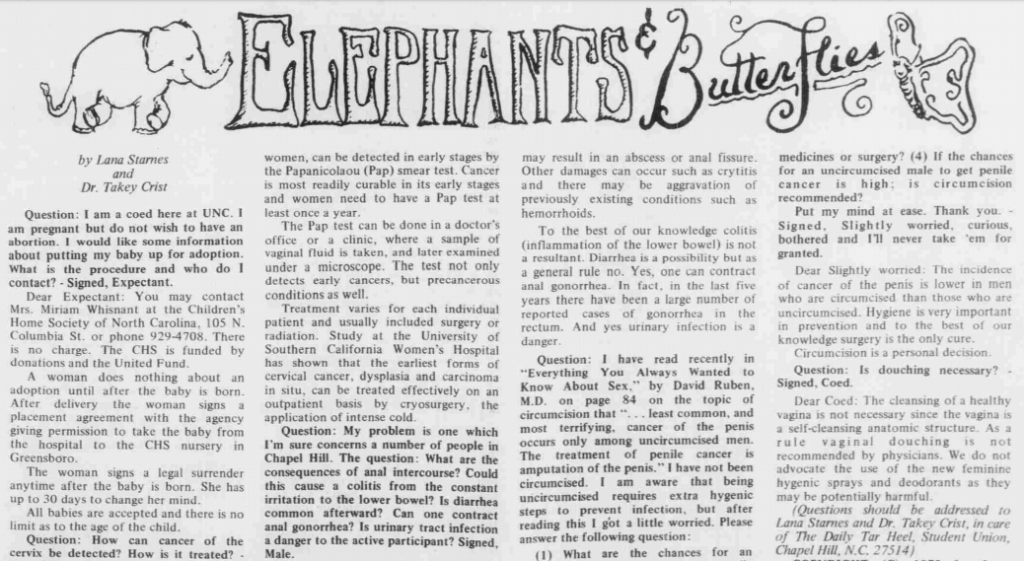

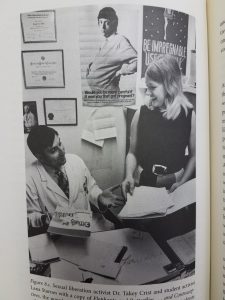

In December 1970, in response to a recognized need for more open dialogue about reproductive health on campus, a student and a faculty member started “Elephants and Butterflies,” a weekly column in the Daily Tar Heel. Created by student-activist Lana Starnes and Dr. Takey Crist, activist and Assistant Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the column featured their responses to anonymous letters about health and sexuality.

Dr. Crist, holding a copy of the Elephants and “Butterflies…and Contraceptives” booklet and Lana Starnes, from “Rebellion in Black and White” by Robert Cohen and David J. Snyder

Some of the reasons Starnes and Crist cited for the necessity of the column were the high rate of unwanted pregnancies and the high rate and danger of illegal abortion (Bobo, 1973). Starnes noted that about 25,000 women sought an illegal abortion in North Carolina annually (Starnes, 1971). A few years earlier, in 1968, campus research showed that 60% of sexually-active women surveyed had not used contraceptives (Morrow, 2006, p. 12). Around the time, UNC administration denied the prescription of birth control to unmarried women, fearing that access to birth control and information would increase sexual activity (Warren, 1967). To make matters more difficult, if a student were unmarried and pregnant or found to have sought an illegal abortion, she would not be permitted to continue school (Unwed Pregnant Student Policy, Collection # 40124).

The column grew out of the sexual health booklet titled “Elephants and Butterflies…and Contraceptives,” co-written by Dr. Crist and released in 1970. To combat stigma and help dymystify human sexuality, Starnes and Crist wrote of their column:

“It is not our purpose to cause embarrasment or fear or shame, but to allow students to examine their educational presuppositions and value judgments concerning human sexuality. We feel your questions are legitimate, necessary and should make us respond thoughtfully, adequately and honestly.” (Starnes & Crist, 1971)

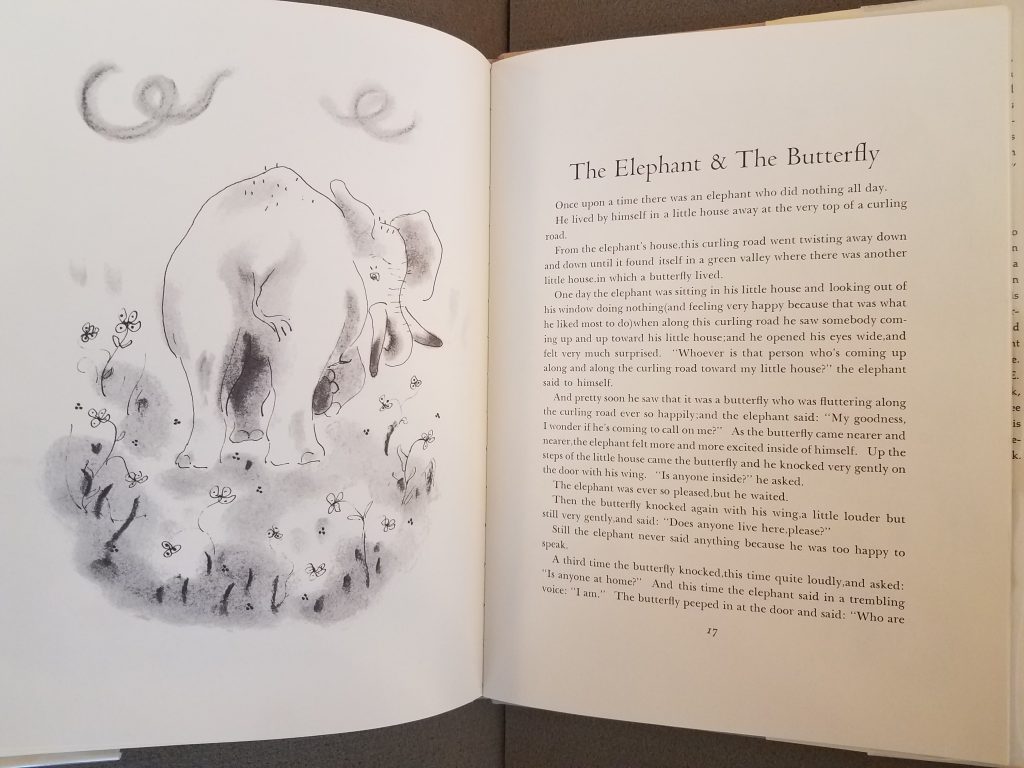

The name of the booklet and column came from that same commitment to openness. It is a reference to the E.E. Cummings fairy tale, “The Elephant and The Butterfly”, a sweet, short story about love and dedication written for Cummings’ daughter (Popova, 2013). The story was printed in the beginning of the booklet, representing sexual relationships as ones that should be entered into with “caring and trust” (Cohen & Snyder, p. 201) In the health booklet, male physiology is described in the “Elephant” section and female physiology in the “Butterfly” section. (Starnes & Cheek, 1970)

E.E. Cummings, Fairy Tales, illustrated by John Eaton [Rare Book Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library]

Subjects covered in the column ranged from how smoking affects sexual functioning (Sept. 6, 1971) to pregnancy after having a miscarriage (March 5, 1973). Sometimes, in leui of questions, readers could match definitions to a reproductive organ diagram (Sept. 25, 1972) or read an informative guide on STDs (October 1, 1973).

In 1972, the March 6th column was left blank in memory of an 18-year old student who died seeking an illegal abortion. That day, a somber message from Starnes and Crist in place of their usual advice asked if her death could have been prevented with proper birth control and counseling, ending with “We mourn in silence.” (March 6, 1972)

The final column was the seventh in a series of columns about contraception (March 4, 1974). They omitted the recurring section requesting that students send in letters, but stated that the next essay (presumably the eighth) in the series would be on the future of birth control. They did not mention whether or not the column would return.

Learn more about Dr. Crist, Lana Starnes and “Elephants and Butterflies” in “Sexual Liberation at the University of North Carolina,” by Kelly Morrow, a chapter in Rebellion in Black and White: Southern Student Activism in the 1960s. (Robert Cohen and David J. Snyder, eds., Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2013). The article is based on Morrow’s 2006 master’s thesis, available in Carolina Digital Repository: https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/d504rm21k.

Sources:

Bobo, M. (1973). Lana Starnes: the woman who helped bring ‘Elephants and Butterflies’ to UNC. The Daily Tar Heel. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1973-02-09/ed-1/seq-1/

Cummings, E. E. & Eaton, J. (1965). Fairy tales. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. https://catalog.lib.unc.edu/catalog/UNCb3123616

OIRA. Fact Book: Bicentennial Edition, 1793-1993. https://oira.unc.edu/files/2017/07/fb1994_bicent.pdf

Morrow, K. (2006). Navigating the “sexual wilderness”: The sexual liberation movement at the University of North Carolina, 1969-1973.

Morrow, K. (2013) “Sexual Liberation at the University of North Carolina.” Rebellion in black and white: Southern student activism in the 1960s. Edited by Robert Cohen and David J. Snyder. The John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore.

Popova, M. (2013). Vintage illustrations for the fairy tales e.e. cummings wrote for his only daughter, whom he almost abandoned. Brain Pickings.

Starnes, L. & Cheek, T. (1970). Elephants and butterflies..and contraceptives. The Daily Tar Heel. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1970-10-11/ed-1/seq-3/

Starnes, L . & Crist, T. (1971). Elephants and Butterflies. The Daily Tar Heel. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1971-08-31/ed-1/seq-50/

Starnes, L. (1971). College loans for abortion? The Daily Tar Heel. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1971-04-08/ed-1/seq-8/

Starnes, L. (1972). Elephants and Butterflies. The Daily Tar Heel. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1972-02-14/ed-1/seq-6/

Starnes L. & Crist, T. (1973) Elephants and Butterflies. The Daily Tar Heel. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1973-04-16/ed-1/seq-6/

Starnes L. & Crist, T. (1974) Elephants and Butterflies. The Daily Tar Heel.

Unwed Pregnant Student Policy, 1967, in the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records #40124, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Warren, V. (1967). Should university health services provide the pill?”. The Daily Tar Heel. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1966-02-03/ed-1/seq-1/