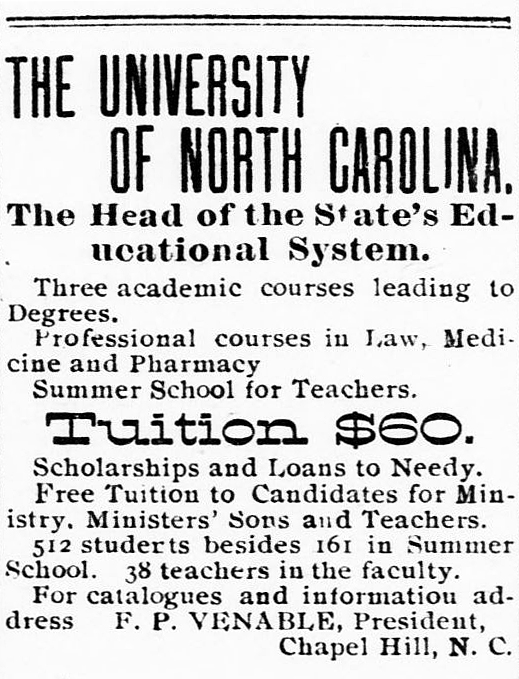

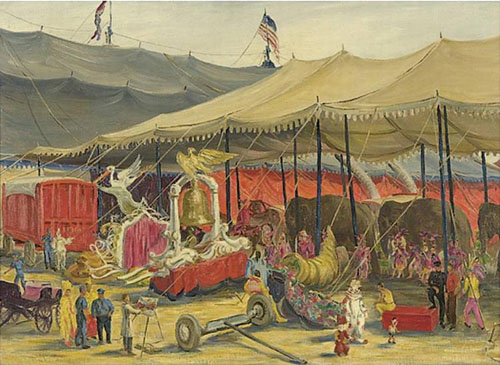

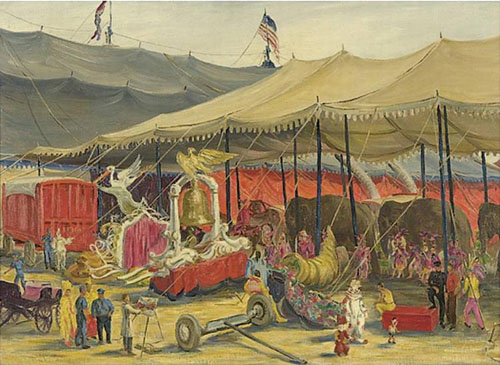

North Carolina Miscellany‘s Charlotte bureau, a.k.a. a certain Mr. Powell, recently came across a post on the Circus Historical Society’s message board seeking information about circuses operating in North Carolina in 1942. The individual who posted the message is trying to determine the circus featured in the Charles Baskeville painting titled Circus Backlot and pictured above. The words June 1942 are written on the rear of the canvas. The post also suggests that North Carolina is included in the title.

A little digging in the vast stacks of the North Carolina Collection and lots of searching on the Web may have yielded an answer. But we’re hoping that readers of North Carolina Miscellany can confirm our theory. And, if nothing else, we’re happy to share with you the story of a once renowned artist with North Carolina roots.

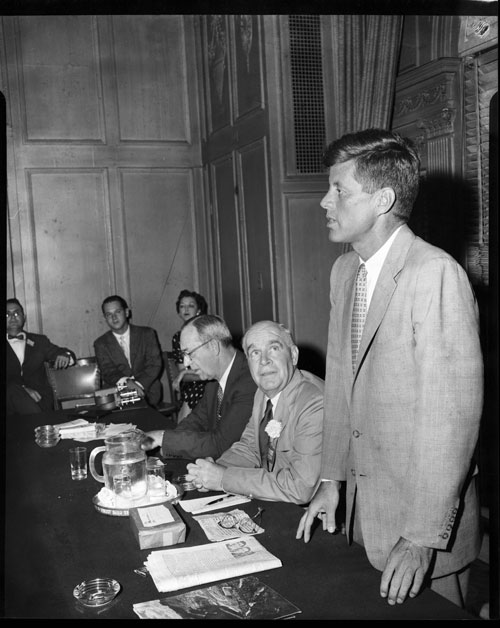

Charles Baskerville Jr. rose to prominence in the 1930s as a portraitist and muralist for the rich and powerful. Those who sat for his portraits included Jawaharlal Nehru, the King of Nepal, Bernard Baruch, William S. Paley, Helen Hayes, the Duchess of Windsor and Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney. His murals decorated the main lounge and ballroom of the ocean liner S.S. America, the bathrooms of New York’s “21,” the Wall Street Club and the homes of such wealthy and famous individuals as boxer Gene Tunney and New York Mets founder Joan Whitney Payson.

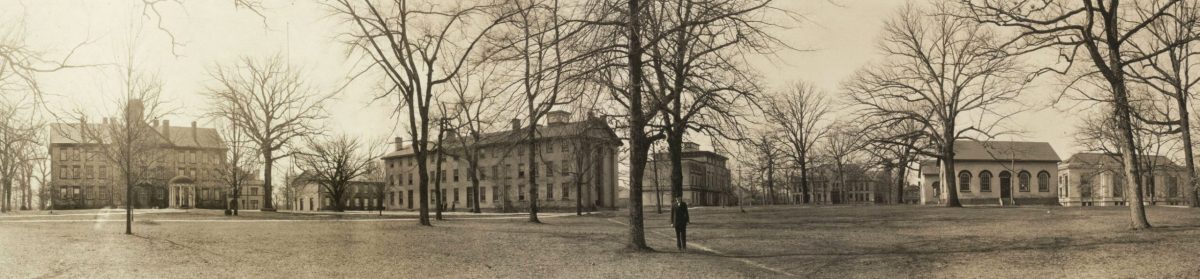

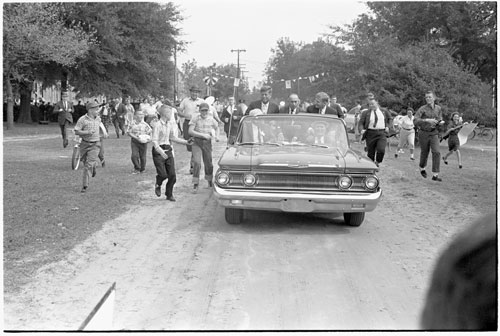

Through his work Baskerville, who was born in Raleigh in 1896 and the son of a UNC chemistry professor, became a darling of the wealthy and hobnobbed with high society. His friends included New York socialite Brooke Astor and John Ringling North, who inherited Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus from his uncles in the 1930s. Baskerville’s friendship with North brought him entree into the world of circus performers and backlots. And he began to travel with the circus, creating backdrops for acts, sketching performers and producing paintings of the animals. During the 1950s, Baskerville produced several covers for Ringling Brothers programs. The 1952 cover features a shapely tiger handler and her charge. And, as Ernest J. Albrecht notes in A Ringling by Any Other Name: The Story of John Ringling North and His Circus a Baskerville painting hung for many years in Jomar, North’s private railway car on the circus train.

So, could it be the Ringling Bros. circus in the Baskerville painting above?

The Ringling Bros. Route Book for 1942 suggests that the circus visited 26 states. But, unfortunately, it doesn’t provide of list of them. The route book does record the cities and towns where Ringling Bros. had stands of two days or longer and no place in North Carolina is included. But it’s also possible that North Carolina was the site of a one-day stand. There were 68 of those in 1942.

The route book also lists the acts or displays that the circus included in 1942. Display 14 reads, “Bridal Bells Ring Out in Clownland. A Mighty and Merry Travesty in Which Pomp and Panoply Have Their Roles-and Rolls.” Then it notes, “The Wedding of Gargantua and Toto.” Is that a wedding bell in the middle of the painting?

As for the wedding….Gargantua and Toto were gorillas. Following the hype that resulted from the release of the film King Kong in 1933, North bought a gorilla for the circus in 1937. Although originally named Buddy, the gorilla was renamed Gargantua by Ringling Bros.’ press department in an effort to make him fit his billing as “the world’s most terrifying living creature.” Indeed, the gorilla could be menacing. His upper lip was curled in a permanent sneer, the result of scarring that occurred when a drunken sailor threw acid at him when he was being transported from Africa as a young animal. Gargantua also occasionally displayed aggressive behavior. He is said to have bitten several who ventured too close, including North in February 1939. Nevertheless, North turned to the animal to give the floundering circus a boost in attendance.

In 1940, hoping to keep alive excitement about Gargantua, North bought Toto, a female gorilla, to serve as the male’s mate. Although the two animals never produced offspring (in fact, they may not have had as much as a one-night stand) the circus billed them as Mr. and Mrs. Gargantua the Great and displayed them in back to back, identical cages inside a specially-designed tent.

The wedding between Gargantua and Toto billed as part of the 1942 Ringling Bros. show didn’t actually include the gorillas. Instead, the clowns staged their own comic interpretation of how such an event might have appeared. Incidentally, the 1942 show also featured the “Ballet of the Elephants,” a dance performed by 50 tutu-clad elephants and 50 ballerinas. The ballet was choreographed by George Balanchine and featured his wife, Vera Zorina, as the principal ballerina. Igor Stravinsky composed the score, which he titled “Circus Polka: For a Young Elephant.” Could the elephants in Baskerville’s painting be waiting for their tutus?

Wanna know more about Baskerville? Read on…..

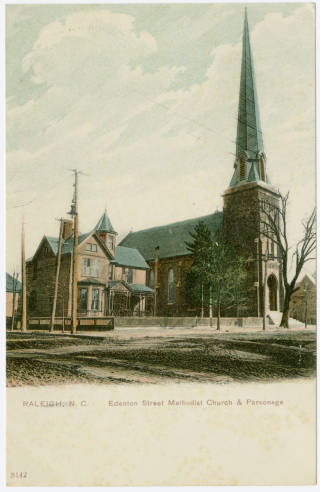

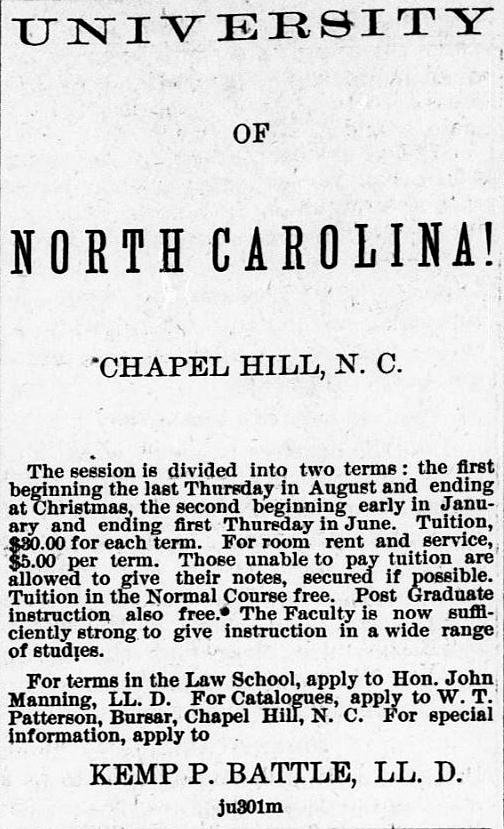

Baskerville was born in Raleigh and, through his mother, a descendant of William Boylan, an early settler of town and one of the publishers of the North-Carolina Minerva. Baskerville’s father, also Charles, had a distinguished undergraduate career at UNC before joining the faculty there. The senior Baskerville was a star fullback for the football team and the first editor of the Tar Heel, as the student newspaper was known then. As a chemistry professor, in 1903 he garnered attention with announcement of his discovery of two previously unknown chemical elements, which he named carolinium and berzelium. Those claims, refuted by later research, proved sufficient enough to attract the attention of administrators of the City College of New York, who invited him to start a chemistry department there.

With the senior Baskerville’s acceptance of that job, the family moved to New York City. Eventually Charles Jr. headed off to Cornell to study architecture. But, with the publication of several of his drawings in the college humor magazine, Baskerville turned his career plans toward art.

The budding artist had yet to complete his studies at Cornell when the U.S. entered World War I. Baskerville joined the Army as a first lieutenant and headed off to France, where, during summer 1918 he was injured by shrapnel and then a short time later gassed. He spent the remaining seven months of his service recuperating in a French hospital and overseeing German prisoners of war. Baskerville also used that time to create a portfolio of battlefield sketches, which Scribner’s Magazine published in July 1919, some five months after he returned from France.

Back at Cornell Baskerville continued his art studies, entering a work in a contest sponsored by the nationally-circulated, satirical magazine Judge. His entry won first place and was featured on the cover of Judge. That work, in turn, led to other jobs as cover illustrator for such magazines as Life, Vogue and Vanity Fair. Upon graduation from Cornell, Baskerville returned to New York City, where he took classes at the Art Student’s League and roamed Broadway speakeasies dressed in top hat and tails. One of those who joined Baskerville in his explorations of the city’s night life was Harold Ross, whom the artist had met during his service in France. When Ross founded The New Yorker in 1925 he tapped his fellow roamer, Baskerville, to write about the nightclub circuit. Baskerville’s short-lived column,”When Nights are Bold,” made its first appearance in the April 11, 1925 issue of The New Yorker under the pen name “Top Hat.” The columns were accompanied by pen and ink drawings of dancers and performers signed by Baskerville. The column ended with the July 11, 1925 issue, when Baskerville sailed for an extended sojourn in Paris.

Eventually Baskerville’s travels took him to such far-flung destinations as India, Morocco, Russia, Japan, China and Bali. In each locale he recorded the sights with paint, pen and ink, always returning to his home base of New York with detailed sketches and sometimes finished works. During the 1930s Baskerville’s star rose in New York social circles and among industry titans. He was the favored portraitist and muralist for the Astors and the Vanderbilts. In fact, Baskerville, a lifelong bachelor, would develop a long friendship and serve as occasional social escort for Brooke Astor.

Baskerville’s works were exhibited throughout the United States. According to Jim Vickers, who penned a remembrance of the artist for the December 18, 1997 Spectator weekly, Baskerville was the first living American to have a one-man show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Other museums in Washington, as well as those in Palm Beach, San Francisco and Springfield, Massachusetts also featured the artist’s works. Baskerville even received recognition in his home state. In 1967 his paintings highlighted the dedication of a gallery at the Greenville Museum of Art.

Vickers wrote that Baskerville produced art “first to please himself, secondly to please his clients, and thirdly to earn a lucrative income.”

As noted in his 1994 New York Times obituary, Baskerville sold paintings until the end of his life and on the day he died he had signed his name to one of his works. John Russell, a former art critic for the Times , told the paper that Baskerville “did not flatter his sitters, but he sent them home from the studio in high good spirits.” And the artist, himself, once said that “people want to be painted the way they actually look. This business about having to flatter them is nonsense.”