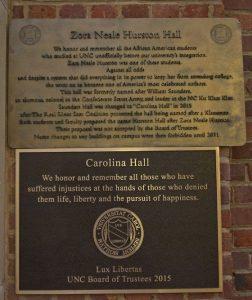

On May 28, 2015, the UNC Board of Trustees voted to remove the name of Ku Klux Klan leader and Confederate Army colonel William Saunders from a campus building and rename it “Carolina Hall.” Additionally, the Board voted to place a 16-year moratorium on renaming campus buildings. The removal of Saunders’ name came after decades of work by student activists on campus, particularly the collaborative efforts of student organizations (the Black Student Movement, Real Silent Sam Coalition, and the Campus Y) in 2014.

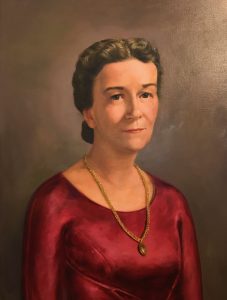

Activists had urged the administration to rename the building for renowned black anthropologist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston. They cited a belief that Hurston attended UNC as a “secret student” in 1940, more than a decade before the first African American students were admitted to Carolina.

Even after the Trustees’ decision, student activists continued to celebrate Hurston’s life and call for a new name for Carolina Hall. In the fall of 2015, student activists held an “opening ceremony” for Hurston Hall. A statement by the Real Silent Sam coalition acknowledged the importance of naming the building for Hurston: “We named this building after Zora Neale Hurston precisely because racist and sexist admissions policies excluded her and other Black women from UNC.”

In March 2017, UNC MFA candidate Jeanine Tatlock added an additional plaque to the building, naming it Zora Neale Hurston Hall and acknowledging that “against all odds and despite a system that did everything in its power to keep [Hurston] from attending college she went on to become one of America’s most celebrated authors.”

From what we can tell, the Board of Trustees never collectively addressed the idea of renaming Saunders Hall for Zora Neale Hurston. However, in a letter to the Daily Tar Heel editor in 2017, UNC Trustee Alston Gardner argued that students never formally proposed the name change from Saunders to Hurston. Responding to the suggestion, Gardner wrote, “of course, proving a secret is difficult, so I applied a reasonableness test and came up short.” Many details of Zora Neale Hurston’s connection to Carolina are unclear, but the question of whether or not she was really a secret student here before UNC integrated in 1951 still remains on many of our minds. After an extensive search of resources in the Wilson Special Collections Library (and some from the University of Kansas’ Kenneth Spencer Research Library) we’ve established the following:

According to Cecelia Moore’s The South as a Folk Play: The Carolina Playmakers, Regional Theatre and the Federal Theatre Project, 1935-1939, in 1934, Zora Neale Hurston met playwright and UNC professor Paul Green and Carolina Playmakers founder Frederick Koch at the National Folk Festival in St. Louis, Missouri (p. 167). Recruited by Koch, Zora Neale Hurston came to North Carolina in 1939 to assume a theater teaching position at North Carolina College for Negroes in Durham (now North Carolina Central University)(Moore, p. 154).

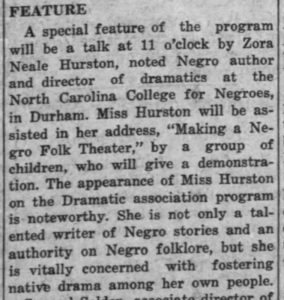

Daily Tar Heel, 7 October 1939, describing Hurston’s presentation at the Carolina Dramatic Association.

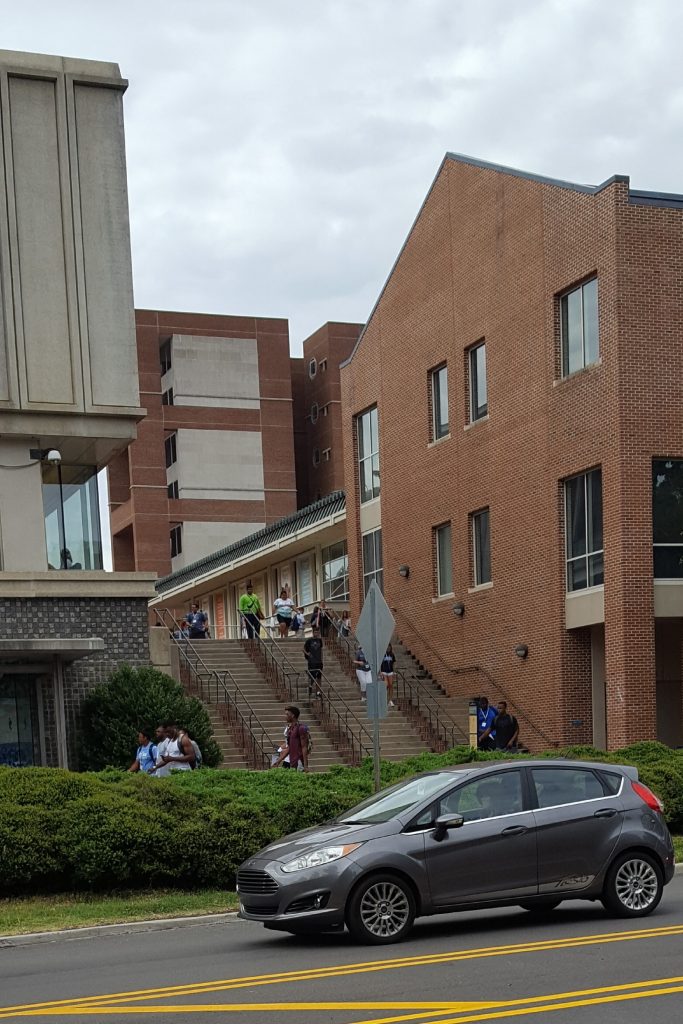

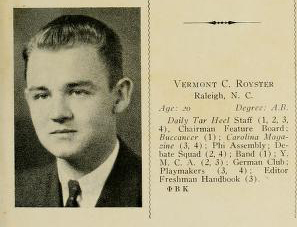

Hurston is now best known for her folktales and novels telling black stories, but in the 1930s she was invested in writing and producing folk plays: plays that highlighted everyday black life. On October 7, 1939, Hurston spoke at the fall meeting of the Carolina Dramatic Association, a statewide organization of theater directors and educators. The group met in Playmakers Theater on UNC’s campus. The following day, the Daily Tar Heel quoted her as telling the group, “Our drama must be like us, or it doesn’t exist.” She wanted to create theater that better exhibited the fullness of black life. Green, drawing from the legacy of the Carolina Playmakers under Frederick Koch, was similarly interested in writing folk plays. He wrote and produced many works and won a Pulitzer Prize in May 1927 for the play In Abraham’s Bosom.

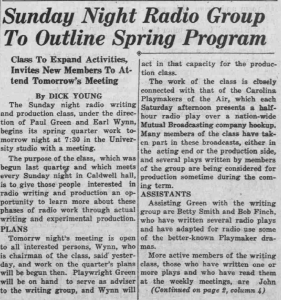

Daily Tar Heel article describing the Sunday night Radio Writing and Production course, lists Zora Neale Hurston among other students, March 30, 1940.

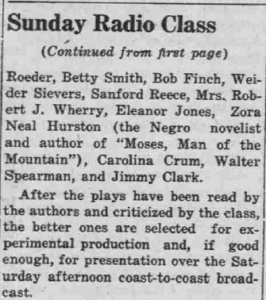

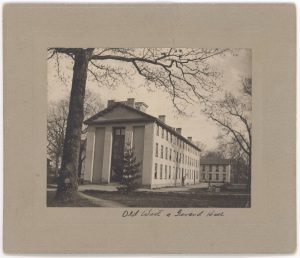

In the spring semester of 1940, Hurston joined Paul Green’s small Sunday night theater class that met at Caldwell Hall. There is conflicting information about this class: Hurston biographer Robert Hemenway writes in Zora Neale Hurston: a Literary Biography that the class was moved to Green’s home due to a complaint from a white student (p. 255), while Laurence G. Avery in A Southern Life: Letters of Paul Green, 1916-1981 says the class was always at Green’s house (p. 312). The March 30, 1940 issue of the Daily Tar Heel lists Zora Neale Hurston among the students in Green’s “Radio Writing and Production” course, meeting Sunday nights in Caldwell. In a 1971 interview with Robert Hemenway, Paul Green said they often had to work “sort of specially separate from the class,” and she would come to his house quite often.

Although Paul Green was the instructor for the course, his relationship with Hurston appeared to be more collaborative. In one energetic letter, Hurston writes to Green imploring him to send someone to record a spiritual she found at a black church in South Carolina. The spiritual could help them in the writing of their play, with the working title John De Conqueror. In the letter, she says, “Now, don’t sit there Paul Green, just thinking! Do something!” (p. 312). She feared a fellow student would record the spirituals and sell them before they could use it in their work. Unfortunately, the recordings weren’t made, and John De Conqueror was never finished.

Daily Tar Heel article describing the Sunday night Radio Writing and Production course, lists Zora Neale Hurston among other students, March 30, 1940.

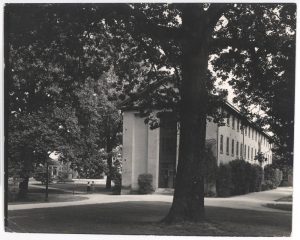

Despite not being officially recognized as a student, the spirit of the plaque students placed on Carolina Hall two years ago is still represented in Zora Neale Hurston’s abundant life as a black scholar. Her work initially received mixed reviews, but by the time she arrived in North Carolina, she had already earned a bachelors degree from Barnard College in 1928 and published several noteworthy books—including one of her most popular works, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Paul Green said in that 1971 interview that he remembered Hurston driving around campus in her “little red sports car” with a “jaunty little tam o shanter” on her head. Students would “jeer” as she drove by. On one occasion, he recalled, even the professors mocked her — she responded by calling “Hi, freshmen! Hi, freshmen!” It seems she never backed down from a challenge.

As Gardner noted, “proving a secret” is a challenge, and one archivists face often. Reference archivists frequently receive questions about aspects of campus history that, for many reasons, went undocumented or unpreserved. It is a struggle to find answers and adequate evidence to support them. It all depends on what has been collected and preserved. When we find these gaps in the historical record, it is frustrating but encourages us to think more deeply about what we’re collecting now and its uses in the future. In the case of Zora Neale Hurston at UNC and many parts of university history that we take extra time to research, we relish in the small crumbs we have but find ourselves hungry for more information.

Learn More: “Saunders Hall” essay in Reclaiming the University of the People: Racial Justice Movements at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Charlotte Fryar, 2019.

Sources:

Frederick H. Koch Papers, 1893-1979.

Letter to the Editor of the Daily Tar Heel

A Southern Life: Letters of Paul Green, 1916-1981

University Archives Web Archives