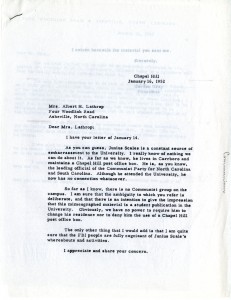

President Gordon Gray’s reply to a concerned North Carolinian, 1952 (From the Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): Gordon Gray Records, 1950-1955, #40008, University Archives)

In 1950, Secretary of the Army and Director of the Psychological Strategy Board Gordon Gray became president of the UNC system. Leading the university at the height of the McCarthy era, Gray received many letters from concerned citizens and parents of students about a supposed student section of the Communist Party at the university. Technically, there was a student chapter of the Carolina District Communist Party in Chapel Hill, but it was an independent local organization. Its publications and pamphlets made their way on to campus, in part, because of the efforts of Junius Scales.

Junius Scales was a labor organizer, civil rights activist, and chair of the Communist Party for North and South Carolina. He came from a wealthy family in Greensboro, North Carolina and secretly became a member of the Communist Party when he was 19. After serving in World War II, Scales finished his Bachelor’s degree at UNC Chapel Hill and started on a Master’s degree, which he did not finish. In the early 1950s, he became more involved with the Communist Party and began distributing publications in support of the Party on the UNC campus.

In writings by Scales found in the records of President Gray, he calls on the public to support peace efforts.

“We young people the world over want peace. We look forward to a college education, and not to military service. Those of us who are students realize that knowledge is found through the free flow of ideas, not through thought control in our colleges and universities and the lies, slanders and omissions of big-money newspapers. We wish for jobs, homes and families after graduation, and w know that in order to have these things the world must have peace.”

[From “A Student Publication, Fighter For Peace, Peace Will Conquer War,” the Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): Gordon Gray Records, #40008, University Archives]

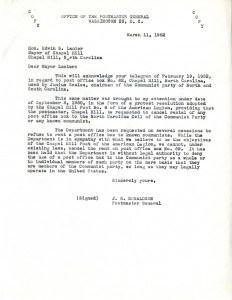

By indicating that the publications were produced by the “Student Section of the Communist Party” and distributing the publications on campus, Scales implied that his organization was a sanctioned student organization. However, there was no official student section of the Communist Party at the university. The address listed for the organization was a post office box in Chapel Hill, and local community leaders asked that the Post Office deny Scales use of the address. However, the Post Office had no legal recourse to stop renting the post office box to Scales.

The U.S. Postmaster General responds to the Mayor Chapel Hill. From the Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): Gordon Gray Records (#40008)

Scales had been under investigation by the FBI since 1951 when he became the Communist Party of the United States District Organizer for the South. In this position Mr. Scales visited and advised Communist Party sections in the states of North and South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and Mississippi. He was eventually arrested by the FBI in 1954 for “conspiring to advocate force and violence,” under the Smith Act. Though Scales himself had not committed an act of violence nor advocated for violence, he was charged for belonging to a party that was thought to do so. After Scales was arrested, the student section of the Carolina Communist Party ceased to exist. However, the overarching Carolina Communist Party, which consisted of the Communist Party sections in the states of North and South Carolina, continued sending out pamphlets to the students at Chapel Hill questioning the constitutionality of the Smith Act.

The Junius Irving Scales Papers are housed in the Southern Historical Collection.

Read more about freedom of speech at Carolina in the online exhibit A Right to Speak and Hear.