The University of North Carolina will meet Duke University on the gridiron for the 103rd time on tonight November 10, 2016. The game will be played in Duke’s Wallace Wade Stadium and will be featured on ESPN at 7:30 p.m. … Continue reading →

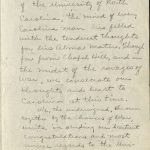

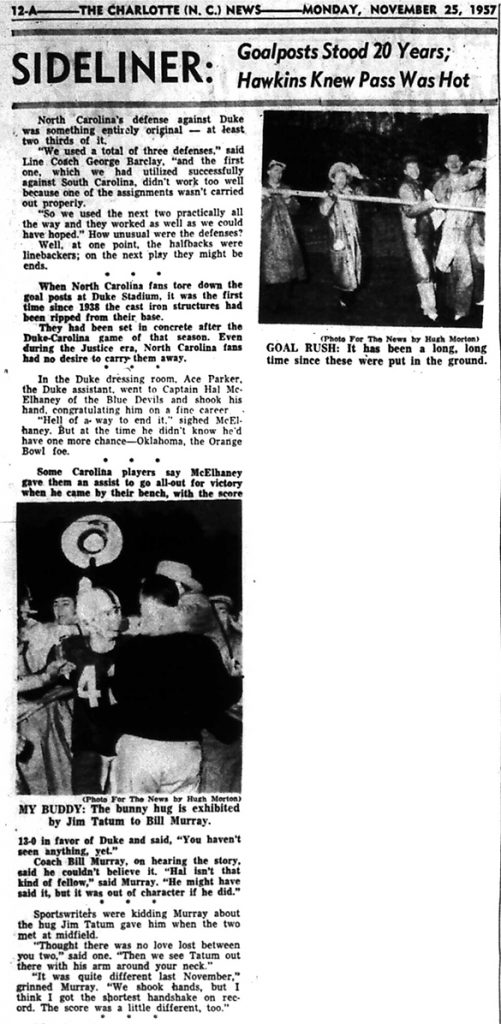

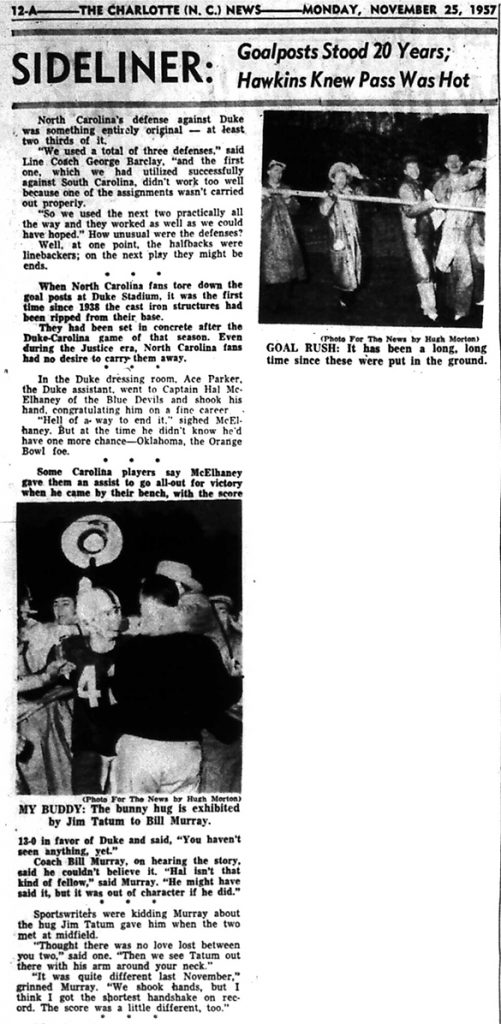

Famous photograph by Hugh Morton made after the 1957 UNC versus Duke football game, as printed in November 25th issue of The Charlotte News.

The University of North Carolina will meet Duke University on the gridiron for the 103rd time on tonight November 10, 2016. The game will be played in Duke’s Wallace Wade Stadium and will be featured on ESPN at 7:30 p.m. Of the 102 previous meetings, Carolina claims 61 wins in the series that dates back to 1888. (Two of those wins, however, have been vacated by a NCAA penalty ruling). With the rivalry about to play out one more time, Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back 59 seasons to one of those UNC victories that Tar Heels like to recall as “one for the books.”

The only way the Tar Heels of 1957 can go is up.

—A preseason comment by UNC Head Football Coach Jim Tatum

When the college football preseason magazines hit the newsstands in late summer of 1957, it seemed a foregone conclusion that Duke would be at the top of the ACC standing when bowl season rolled around in early 1958. Durham Morning Herald Sports Editor Jack Horner (Hugh Morton liked to call him “Little” Jack Horner), writing for the Street and Smith’s Football 1957 Yearbook, said, “The Blue Devils have the potential to finish atop the loop and rank among the nation’s elite.” Carolina, having finished the 1956 season with 2 wins, 7 losses, and 1 tie, was predicted to finish a distant fourth at best.

Carolina kicked off the season with a 7-0 home loss to North Carolina State, but got things together and won the next three games, one of which was a 13-7 win against sixth-ranked Navy in Chapel Hill on October 5th—a game many Tar Heels call one of Carolina’s greatest. Duke stormed into the season with five straight wins and by week number six they were ranked fourth nationally behind Oklahoma, Texas A&M, and Iowa.

Carolina won two of its next four games, while Duke’s season started to slip a bit. By the time the two teams reached their big rivalry game on November 23rd, the Tar Heels and the Blue Devils didn’t seem very far apart. Carolina had a 5-3 record; Duke was 6-1-2, and their ranking dropped to eleventh. Duke was still favored to win the game. In fact, Carolina hadn’t beaten Duke in eight years since its historic 21-20 victory in 1949.

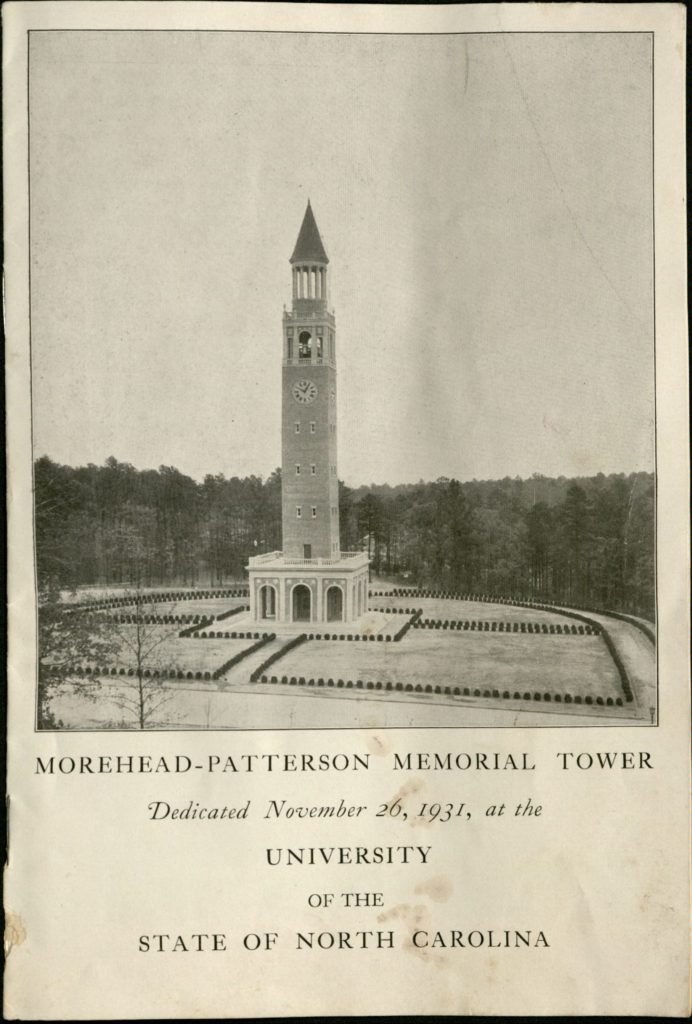

Early on Thursday, November 21st, the Duke Stadium (it’s now named Wallace Wade Stadium) crew put down twelve large squares of plastic to cover and protect the field from the predicted wet weather. The lead-ups to the Carolina-Duke football games have always been exciting and the ’57 game was no different despite that cold, rainy weather. On Friday, November 22nd, Tar Heel students staged the “Beat Dook Parade,” while over in Durham students and alumni enjoyed a huge, twenty-foot bonfire and pep rally.

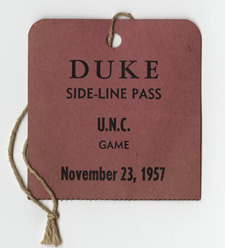

Game day dawned wet and cold as predicted, but by midday the rain had stopped to the delight of the 40,000 fans in attendance; the 40-degree temperatures, however, remained. For the second time in three years, the game was on TV. The 1955 game received national attention, but the ’57 affair coverage came from Castleman D. Chesley’s newly-formed regional ACC Network. Just before kickoff, the Duke cheerleaders rolled the Victory Bell across the field and delivered a basket of oranges to the Carolina cheering squad—just a reminder of Duke’s “next?” game: the Orange Bowl in warm Miami.

November 23, 1957 was also a special day for another reason: Tar Heel football legend Charlie Justice and his wife Sarah Alice were celebrating their 14th anniversary. Coach Tatum had invited Justice to join the team on the sideline that afternoon, and when photographer Hugh Morton spotted his friend on the field, he of course took a picture. The Morton image would become a featured picture in the 1958 biography Choo Choo: The Charlie Justice Story by Bob Quincy and Julian Scheer, and can be found on page 121.

Two Carolina player buses arrived about 1 p.m., and the first person off the second bus was Coach Tatum wearing his big Texas-style hat. At 2:05 PM it was time for the 44th meeting between the two old rivals. Duke won referee John Donohue’s coin toss and elected to receive. Fifteen plays later, Duke’s Wray Carlton scored putting the Blue Devils ahead 6 to 0 after 7 minutes of play. Five minutes later Carlton scored again. This time he made the extra point and Duke went up 13-0. Then with 3:40 left in the first half, Carolina’s Giles Gaca scored making the halftime score 13-7, Duke.

On its second possession of the second half, Carolina took the lead when Buddy Payne caught quarterback Jack Cummings’ 19-yard pass for a touchdown. Phil Blazer’s PAT made the score 14-13 with 10:10 remaining in the third quarter. (It was the first time Carolina had led Duke since the second quarter of the 1951 game). Smelling victory, Carolina went back to work and six minutes later, Cummings sneaked over to give Carolina an 8-point lead at 21-13. The fourth quarter was scoreless.

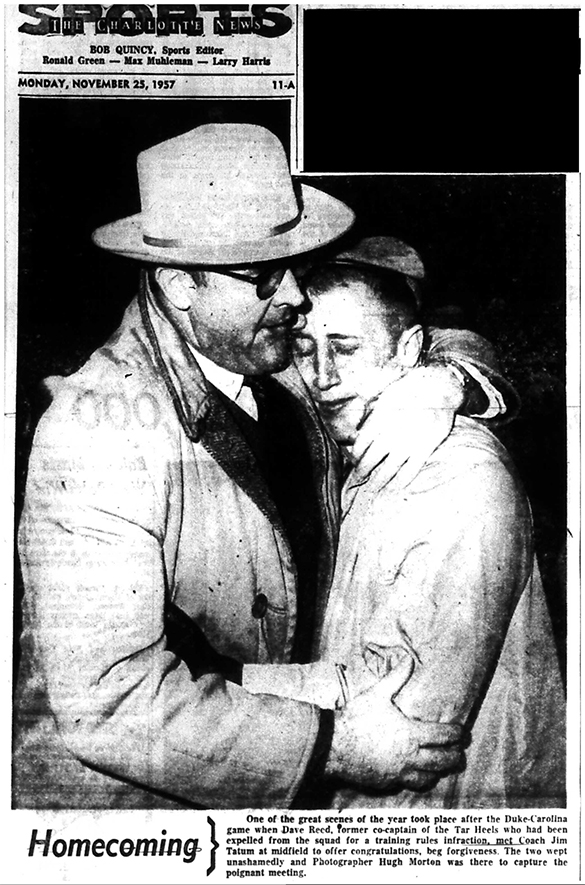

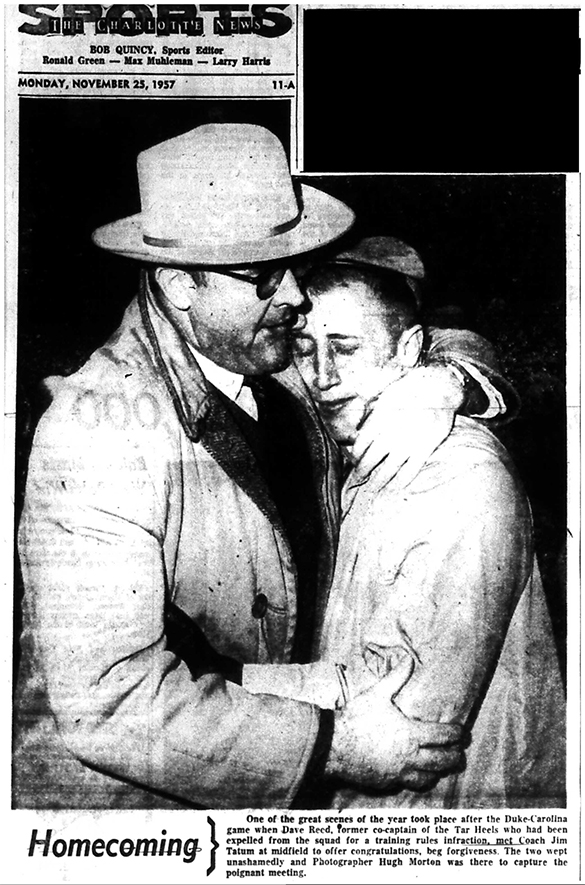

The Charlotte News Sideliner column included two Morton spot-game photographs.

Following the final gun, jubilant Tar Heels tore down the goal posts in celebration as Coach Tatum got a ride on the shoulders of his players and fans. Charlie Justice was one of the first to grab Tatum’s hand and Morton photographic contemporary Harold Moore’s Herald-Sun picture of the hand-shake made the front cover of the 1958 UNC Football Media Guide.

Following the traditional coaches handshake, Coach Tatum sought out some of his players for more celebrations. Then, a Tar Heel player who had been forced the watch the game from the sideline reached out to Tatum. First string quarterback Dave Reed, who had been suspended from the team earlier in the season for breaking team rules, embraced the coach in an extremely emotional moment. “I would have given a million dollars to help win this game,” cried Reed. Said Tatum, “Son, you know it hurt me more than it did you.” Morton’s photograph of the scene is priceless.

In his news conference following the game, Coach Murray said “We were in a commanding position with a two-touchdown lead and we let them get away.” In the Carolina dressing room, Coach Tatum simply said, “It is certainly my greatest thrill in football. It’s the happiest day I’ve ever known. How about the way those boys came back? Thirteen points down, golly!” That’s saying a lot about this particular game. Tatum won a national championship at Maryland in 1953.

Overtime by Stephen Fletcher

Knowing that Hugh Morton had sideline access during the game, I searched through the North Carolina newspapers that typically used Morton’s football photographs, but I never found a published game-action photograph. Most newspapers published photographs made by their staff photographers. Of the half-dozen or so newspapers I examined, only The Charlotte News published Morton’s photographs. There may be game-action photographs from that day hidden in the hundreds of unidentified football negatives in the collection, but thus far none have been located. Currently there are ten positively identified Morton negatives made either on the sidelines or in the stands during the game, or during the postgame celebration.

Knowing that Hugh Morton had sideline access during the game, I searched through the North Carolina newspapers that typically used Morton’s football photographs, but I never found a published game-action photograph. Most newspapers published photographs made by their staff photographers. Of the half-dozen or so newspapers I examined, only The Charlotte News published Morton’s photographs. There may be game-action photographs from that day hidden in the hundreds of unidentified football negatives in the collection, but thus far none have been located. Currently there are ten positively identified Morton negatives made either on the sidelines or in the stands during the game, or during the postgame celebration.