Prolog

It’s a curious malady that sweeps the ACC nation just before most of us catch spring fever. Many of us deal with the disorder by sitting in front of our TV sets for hours listening to basketball announcers and analysts drone on with a strange and curious language that only those who are infected with the ailment can understand:

“With the game on the line, he tickles the twine with the 3-ball from downtown, to get the “W” and advance to the next level of the big dance and now with a chance to win all the marbles up for grabs . . .”

It’s known as “March Madness” and there is no known cure.

The Madness is upon us with the 2016 Atlantic Coast Conference Men’s Basketball Tournament on RayCom Sports and ESPN, but what would it be like without that wall-to-wall TV coverage? There was a time in the early days when ACC basketball was only on radio, but one man saw a bright future for the sport on TV.

Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard profiles the man who is often called the father of ACC basketball on television, C.D. Chesley.

He put ACC basketball on the map, about 10 years ahead of everyone else, and they are still trying to catch up.

Hugh Morton, March 8, 2003

In the early 1950s sports television was nothing like it is today. I remember as a little kid watching the Washington Redskins on Sunday afternoons at 2:00 on the Amoco Redskins Network. There were no replays, so in order to see a favorite play for a second time, I had to wait until the following Friday night when the local TV station ran a program called National Pro Highlights. The program, produced by a company in Philadelphia called Tel Ra Productions, showed filmed highlights of the preceding Sunday’s games.

Castleman DeTolley Chesley was a member of the production team at Tel Ra. Chesley had a football background having played freshman football at UNC in 1934. He then moved to the University of Pennsylvania where he was football captain and was also a member of the Penn traveling comedy troupe. Following graduation he became Penn’s athletic director, he but kept his finger on broadcasting’s pulse. Chesley later worked with both ABC and NBC coordinating college football coverage with the NCAA.

During the 1956–1957 college basketball season, Chesley became intensely interested in the UNC Tar Heels coached by Frank McGuire as they worked their way through an undefeated season. The 27 and 0 Tar Heels then beat Yale in Madison Square Garden during the first round of the NCAA Tournament. At this point, Chesley made his move. Being familiar with the NCAA ins and outs, he was able to set up a three-station regional network for the finals of the Eastern Regional played at the Palestra in Philadelphia. Although station WPFH-TV in Wilmington, Delaware was the switching point, the three stations were in Durham, Greensboro, and Charlotte. Matt Koukas, a former Philadelphia Warrior NBA star, called the play-by-play.

Even before Carolina had won the two-game regional in Philly, Chesley was already setting up the network for the national finals in Kansas City, Missouri and added two additional stations. The semi-final with Michigan State and the final with Kansas were both triple-overtime games. Some folks who watched those two games say that the madness for ACC basketball was born that weekend. Castleman D. Chesley would most likely agree with those folks.

The next logical step was to approach athletic directors at ACC schools about the possibility of doing weekly football and basketball games during the regular season. In the beginning, ADs and head coaches were not in favor of adding TV to the schedule. They were afraid that people would stay home and watch on TV, rather than attend the games. Chesley was able to convince them otherwise, pointing out how television could be used as a recruiting tool as well as fund raising opportunities.

On October 12, 1957 the first ACC football TV game was broadcast, a game from Byrd Stadium in College Park, Maryland between the University of Maryland and Wake Forest. Charlie Harville and Jim Simpson made up the on-air broadcast team. Three other games were telecast during the ’57 football season: one from NC State, one from UNC, and one from Duke. While the football games were successful, Chesley had his eye on basketball. On December 7, 1957, the first ACC regular season basketball game was telecast on a regional network. The game was Carolina vs. Clemson from Woollen Gym on the UNC campus.

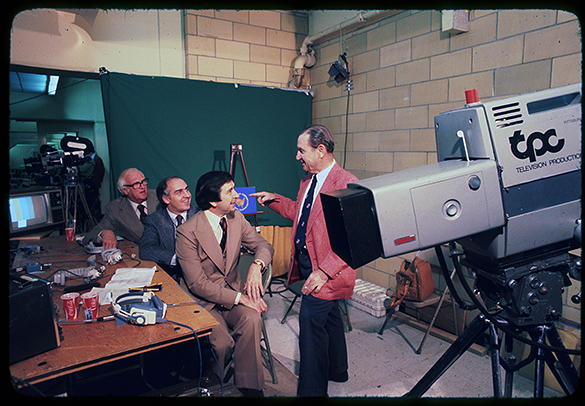

Seated are (L to R) Bones McKinney, Billy Packer, and Jim Thacker, with Castleman Chesley (standing) behind the scenes at UNC-Chapel Hill versus Marquette basketball during the 1977 NCAA finals in Atlanta, Georgia.

In those early days, the C.D. Chesley Company consisted of three people: Irving “Snuffy” Smith, Peggy Burns, and Mr. Chesley. From the beginning Chesley used equipment from WUNC-TV and students from the University’s Radio, Television, and Motion Picture Department. WUNC-TV’s director John Young managed the personnel and equipment. Play-by-play broadcasters like Harville, Simpson, Dan Daniels, Woody Durham, and Jim Thacker, and analysts like Bones McKinney, Billy Packer, and Jeff Mullins were brought in to handle the on-air while directors like John Young from WUNC-TV, Norman Prevatte from WBTV in Charlotte, and Frank Slingland from NBC-TV in Washington called the shots, often from an old converted Trailways bus that UNC-TV used in the early days.

Television coverage of ACC basketball caught on just like Chesley said it would, and his main sponsor Pilot Life Insurance Company became about as famous as the ACC teams. People across the ACC nation could sing along . . .

Sail with the Pilot at the wheel,

On a ship sturdy from its mast to its keel . . .

C.D. Chesley was pleased with ACC basketball but he was always looking for additional challenges. In 1962 and ’63 he produced TV coverage of the Miss North Carolina Pageant to a regional network of station across the Tar Heel state, and in 1964 he produced regional coverage of the Greater Greensboro Open Golf Tournament.

Chesley was always on the lookout for more football coverage. In the mid-1960s he started Sunday morning replay coverage of the preceding Saturday’s Notre Dame games; in 1967 was able to get Hall of Fame Broadcaster Lindsey Nelson to do the play-by-play and Notre Dame Heisman Trophy winner Paul Hornung to do the color commentary. At one point the Notre Dame games were featured on 136 stations and Nelson became known as that “Notre Dame announcer.”

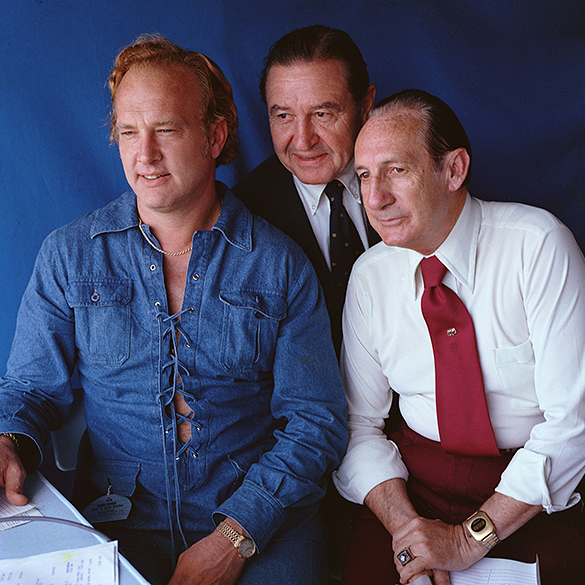

Football commentator and former quarterback Paul Hornung (left) and sportscaster Lindsey Nelson (right), while doing play-by-play for a UNC-Chapel Hill vs. Notre Dame football game. Sports broadcast producer Castleman D. Chesley at center. The year 1975 appears to be printed on Hornung’s employee tag. Notre Dame scored 21 points in the fourth quarter to defeat the Tar Heels 21-14 at Kenan Memorial Stadium on October 11, 1975.

C.D. Chesley started small but his broadcasts were always first class productions. By the 1970s he was broadcasting two ACC basketball games a week. On January 14, 1973 just before the Washington Redskins met the Miami Dolphins in Super Bowl VII, Chesley put together a patch-work national network for the ACC basketball game between North Carolina State and Maryland. It was big time and NC State All America David Thompson became a national sensation.

The C.D. Chesley Company and ACC basketball continued as household names for twenty-four years through the 1981 season. At that point ACC basketball was so big that other broadcasters with bigger budgets wanted in on the action. Chesley’s one million-dollar rights fee could not compete with the likes of MetroSports who offered three million for the 1982 season and RayCom Sports of Charlotte who paid fifteen million for the rights for three seasons starting in 1983. RayCom continues today as the network for ACC basketball.

At the 1977 Atlantic Coast Conference Basketball Tournament, Castleman D. Chesley received a plaque from ACC Commissioner Bob James in recognition of Chelsey’s vision in establishing the ACC Television Network. (Photograph cropped by the editor.)

“His place in the history of ACC basketball is phenomenal, getting the sport out there in front of the public,” said Tar Heel broadcaster Woody Durham in a 2003 interview. “We all knew how exciting ACC basketball was, but here was a guy who came along and let the public see it.”

On April 10, 1983, Castleman D. Chesley lost his battle with Alzheimer’s. He was laid to rest in a small cemetery near his home at Grandfather Mountain. He was 69 years old.

Four years later the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame inducted Chelsey in the spring of 1987. Hugh Morton and Ed Rankin, in their 1988 book, Making a Difference in North Carolina, devoted eight pages of words and pictures to “the man who put ACC basketball on the map.”