In March of 2015, the Army stated that women who had served as Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) in World War II were not eligible for burial in Arlington National Cemetery. This was a reversal of the 2002 decision that … Continue reading →

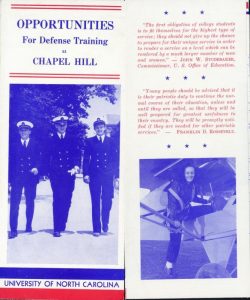

“Opportunities for Defense Training at Chapel Hill” brochure,” UNC Libraries, accessed February 23, 2016, http://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/items/show/2686.

In March of 2015, the Army stated that women who had served as Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) in World War II were not eligible for burial in Arlington National Cemetery. This was a reversal of the 2002 decision that allowed them to be interred at Arlington with full military honors. The Senate and the House now have bills on the floor to overturn the Army’s decision. This controversy has sparked a renewed interest in who the WASPs were and what they did during their service in World War II.

The Women Airforce Service Pilots were a group of over 1,000 women that ferried aircraft around the country, towed dummy aircraft during live artillery training, taught as flight instructors and tested new planes. This freed up qualified male pilots for combat duty overseas. The program began in 1942 as two separate branches, which then merged under the WASP name in 1943. During their time, the WASPs flew every military aircraft available and were trained in everything the men did, except combat exercises. The very first female pilots in the program had to enter the program with at least 200 hours of flight time. That is where the story brings us to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

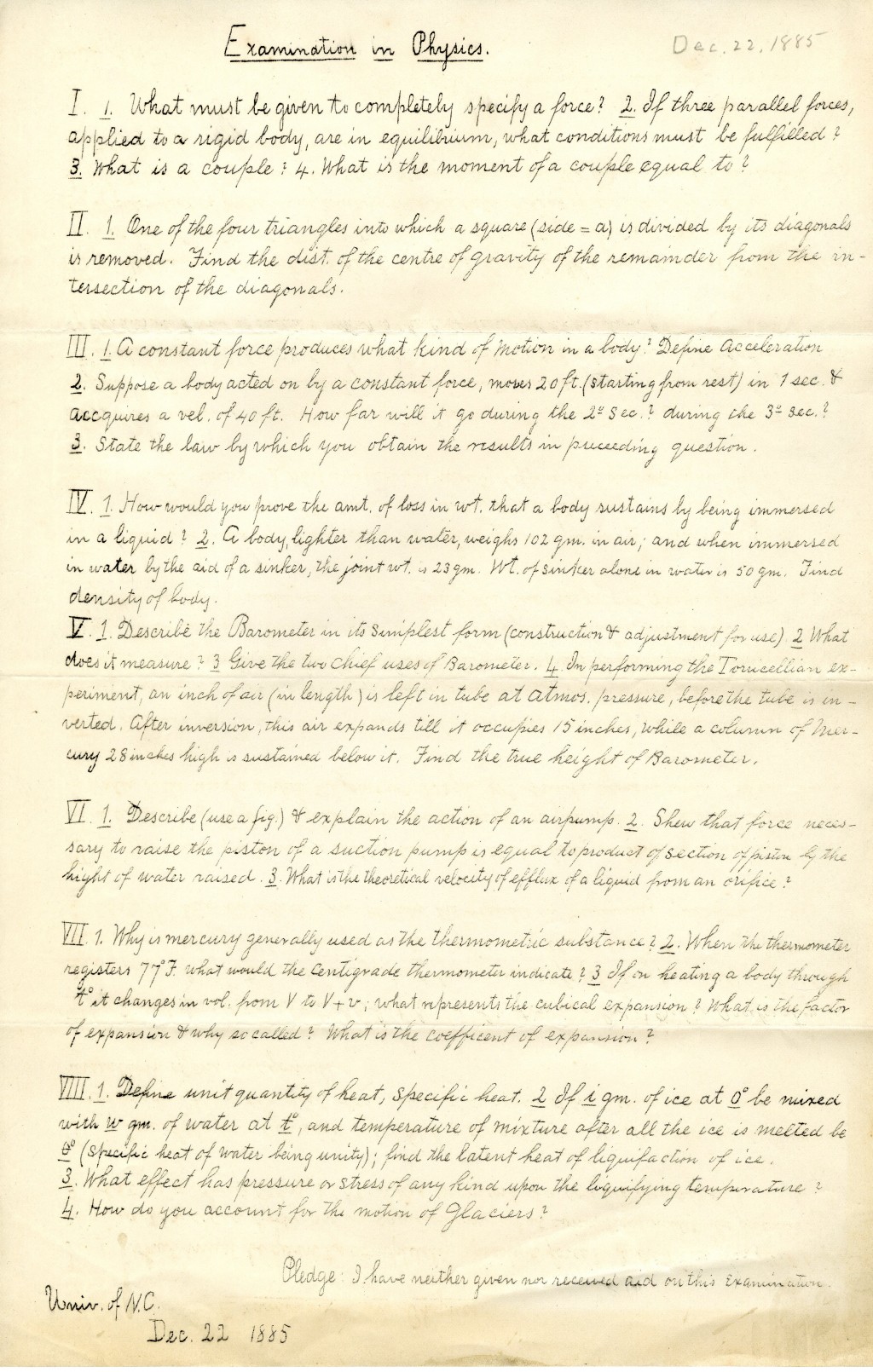

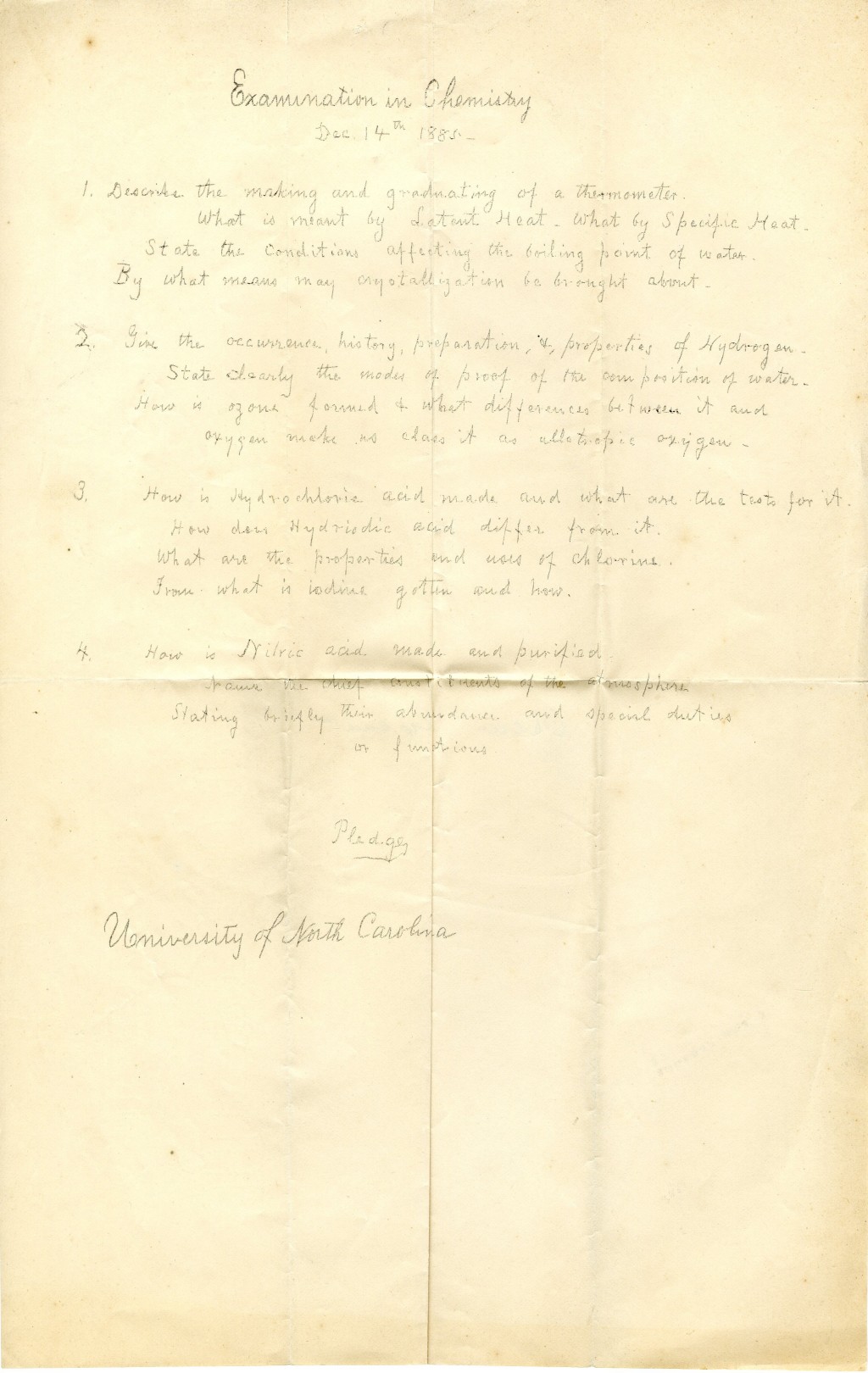

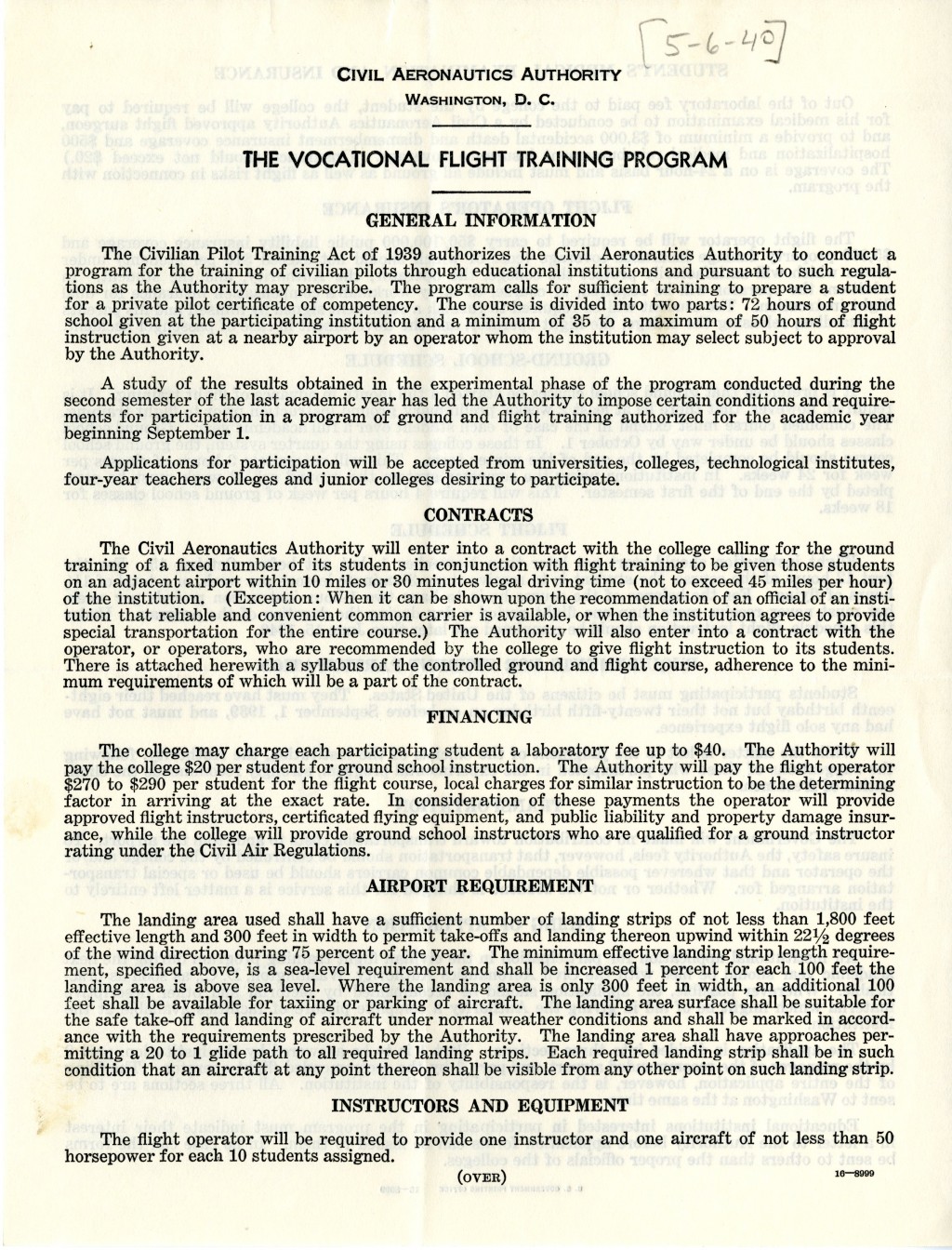

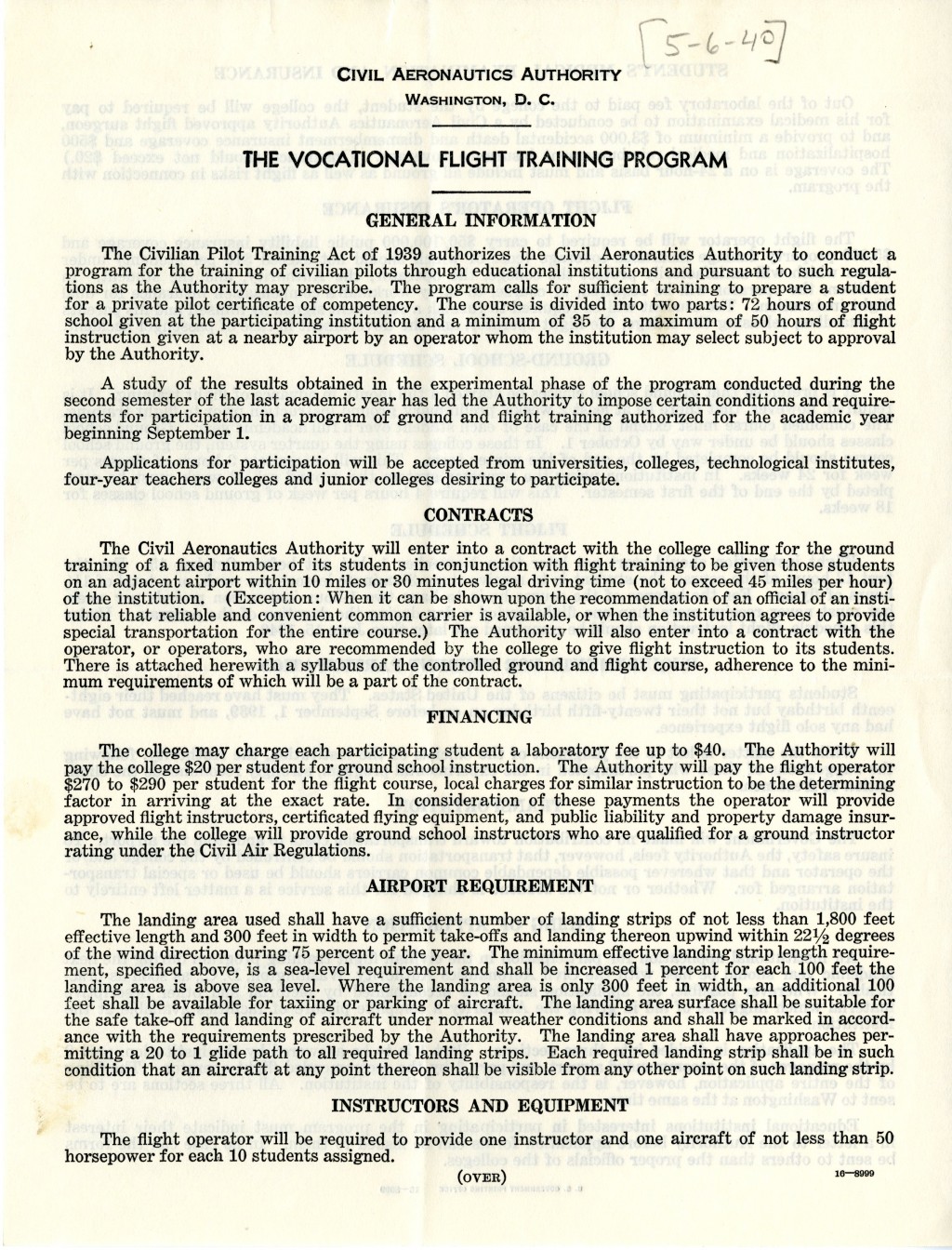

[CAA requirements for a Civilian Pilot Training Program, from the Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): Frank Porter Graham Records, 1932-1949 , #40007, University Archives]

The UNC System was home to a Civilian Pilot Training Program. N. C. State was the first school in the system to host the program. Later, UNC Chapel Hill and North Carolina A&T started their own versions of the program, along with Duke and other colleges around the state. Any student, male or female, was allowed to take the ground portion of the classes for college credit. These classes taught basic aviation theory as well as airplane maintenance. Ground classes were known as primary training. Women students took these classes and anticipated that they would be allowed to continue into flight training.

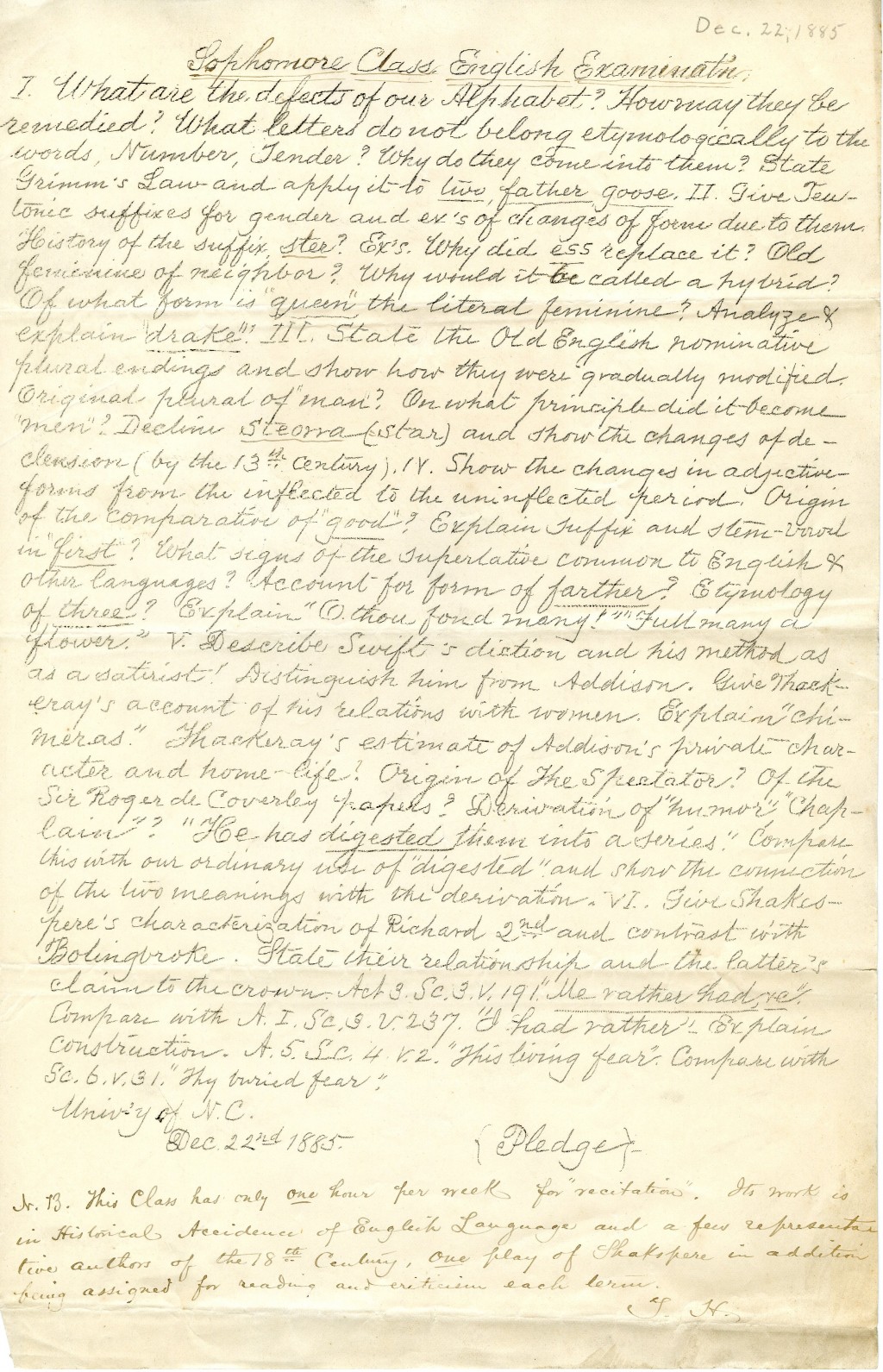

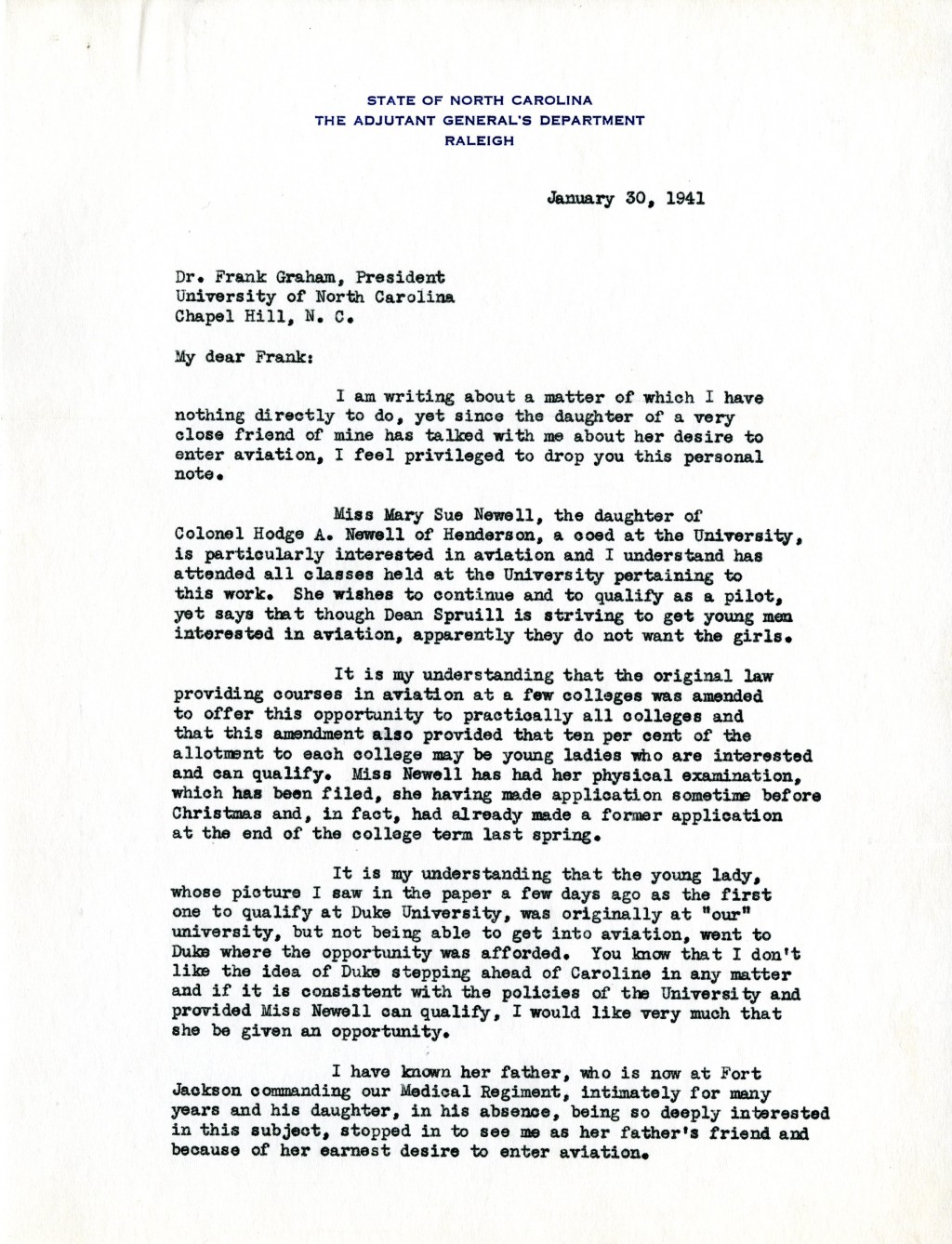

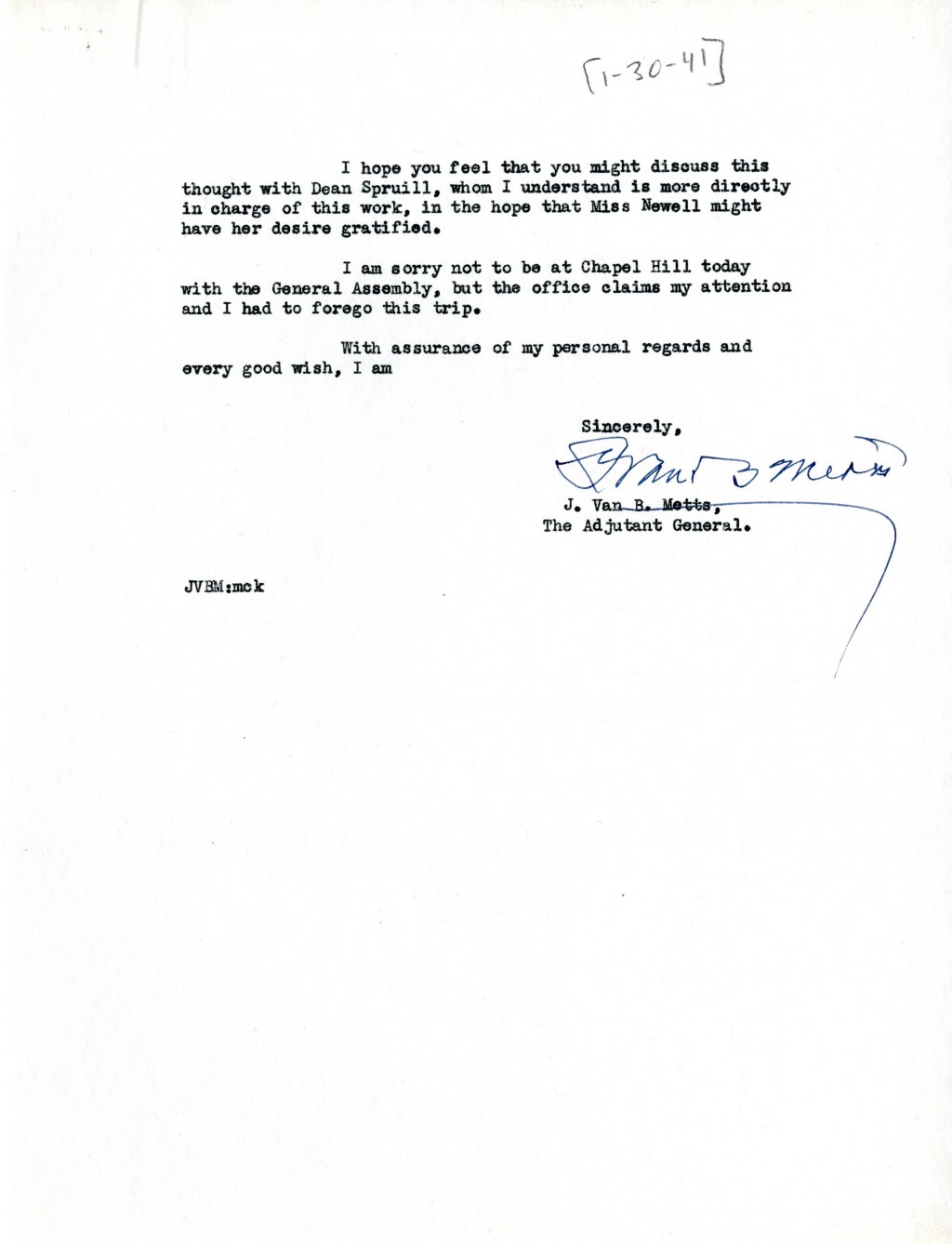

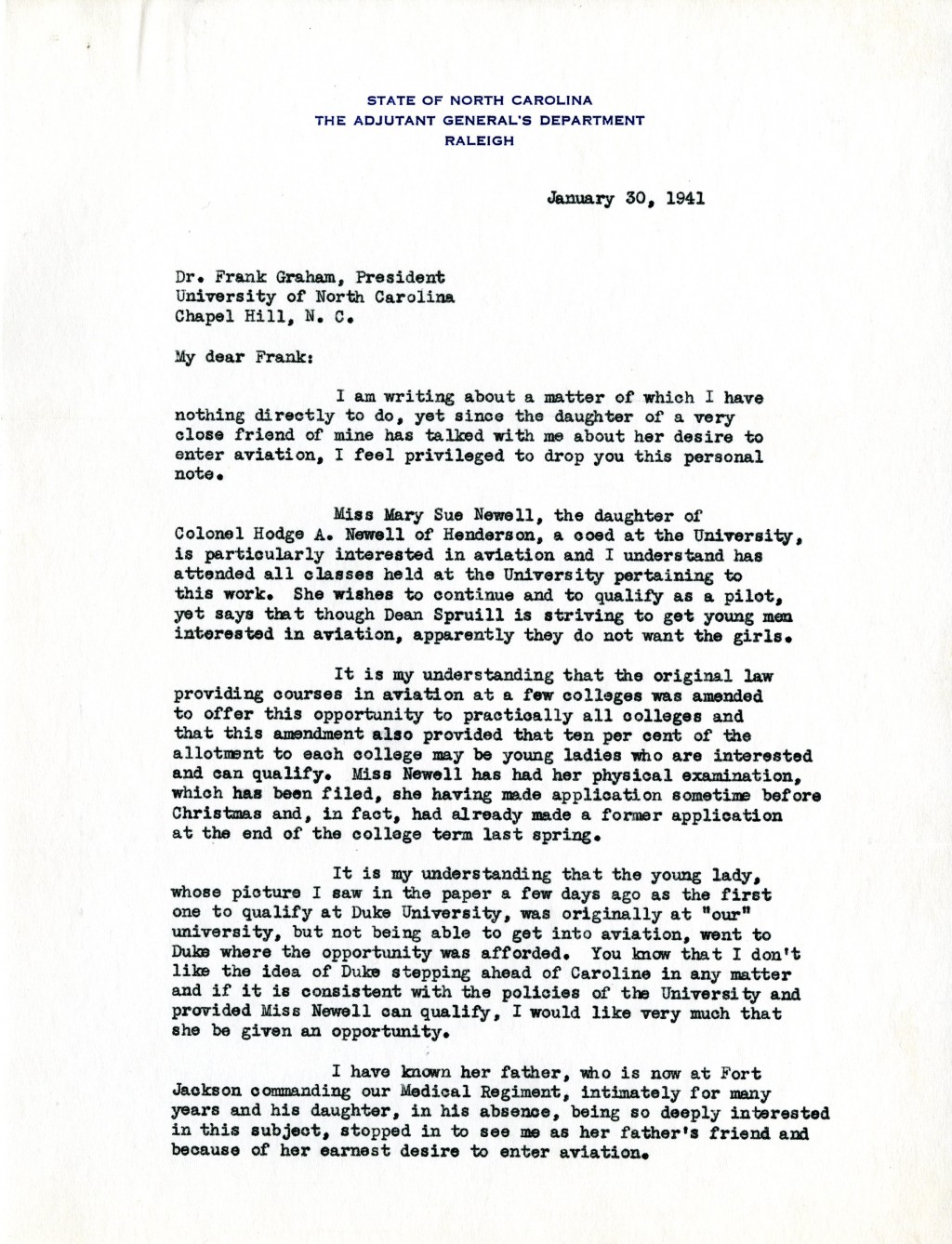

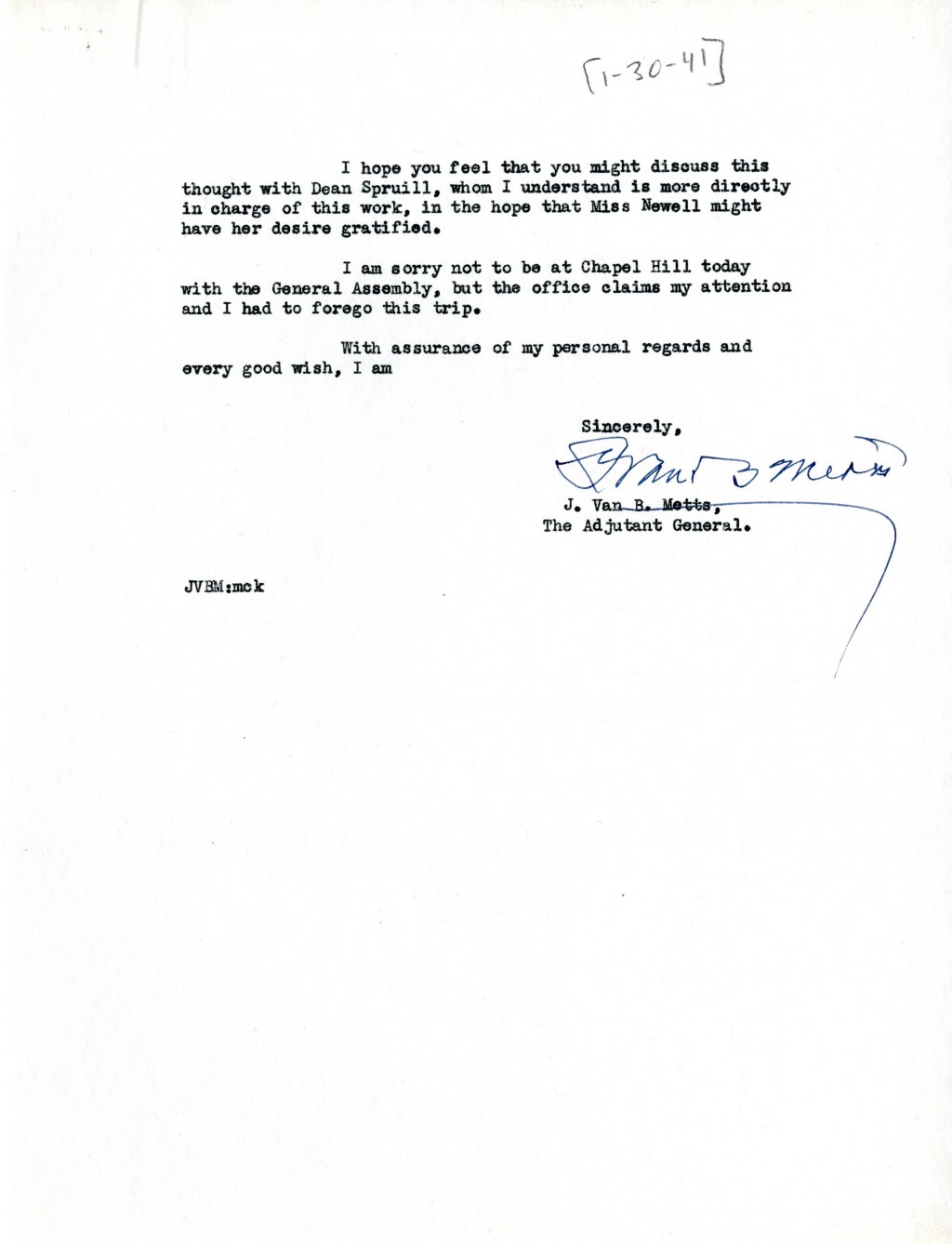

[Letter inquiring about allowing a female student into flight training, from the Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): Frank Porter Graham Records, 1932-1949 , #40007, University Archives]

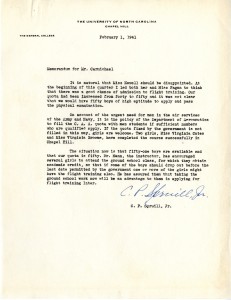

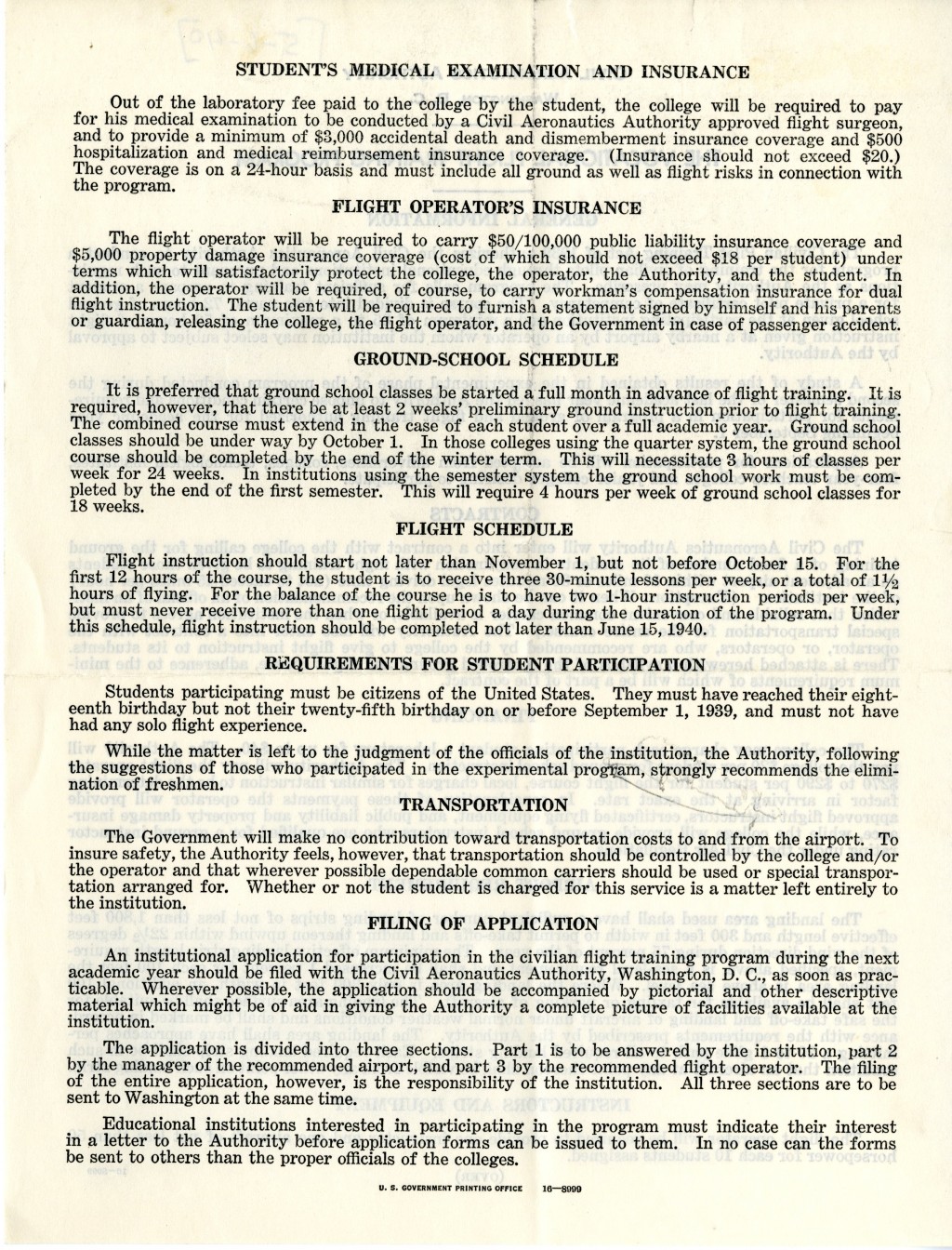

However, actual flight training, or secondary training, was limited to a quota imposed on the university by the Civilian Aviation Authority. The CAA provided most of the funding for flight training and was therefore able to dictate who could participate in secondary courses. The entire purpose of the Civilian Pilot Training Program was to feed the graduates directly into military service and women were not allowed to fly at all in a military capacity before the WASPs program. Therefore, women were only allowed into flight training when the total number of qualified male pilots was less than the quota allotted.

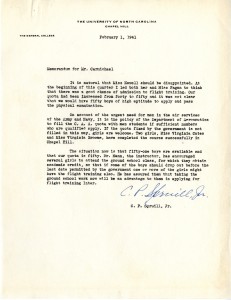

Memo explaining CAA quotas, from the Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): Frank Porter Graham Records, 1932-1949 , #40007, University Archives

The UNC administration did all they could to prove that discrimination was not the reason female trainees had a difficult time getting into flight training, and celebrated the women who made it through both parts of the program. The first woman to complete the entire Civilian Pilot Training Program at UNC, including both ground and flight training, was Virginia Broome. She graduated from UNC in 1942 and became a WASP in 1943. As a ferry pilot she, ferried completed military aircraft from factories to the point of embarkation. Only four women completed the entire course of training at UNC. Of these four, only Virginia Broome (later Virginia Broome Waterer) became a WASP.

For more information about the University of North Carolina during World War II, see the online exhibit A Nursery for Patriotism: The University at War, 1861-1945.

UNC alumni discuss items they contributed to an exhibition about Carolina fashion. On view through June 5 in Wilson Library. Continue reading

UNC alumni discuss items they contributed to an exhibition about Carolina fashion. On view through June 5 in Wilson Library. Continue reading