This Month in North Carolina History

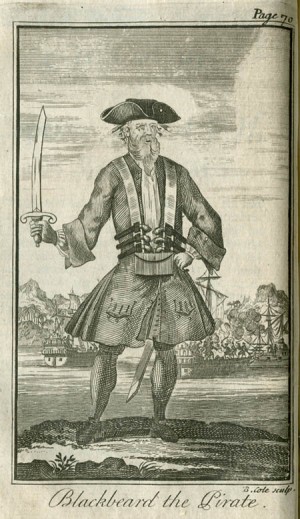

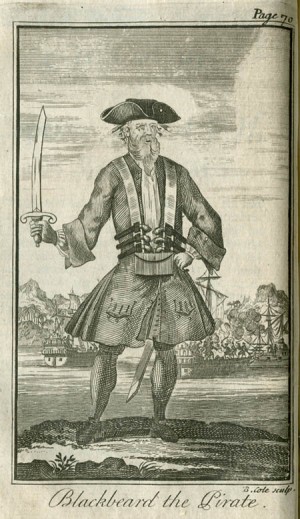

The 1710s have been called the “golden age of piracy.” Pirate ships roamed the Atlantic Ocean, preying upon busy commercial ports in the West Indies and along the coast of North America. One of the most notorious of the pirates, Edward Teach, better known as “Blackbeard,” was a frequent visitor to North Carolina and it was here, in November 1718, that he was captured and killed.

The 1710s have been called the “golden age of piracy.” Pirate ships roamed the Atlantic Ocean, preying upon busy commercial ports in the West Indies and along the coast of North America. One of the most notorious of the pirates, Edward Teach, better known as “Blackbeard,” was a frequent visitor to North Carolina and it was here, in November 1718, that he was captured and killed.

Edward Teach was from Bristol, England, a town on the Avon River in southwest England, which produced many pirates. Teach served on a privateer during Queen Anne’s War (1701-1714). Privateering was, in a sense, legalized piracy. The British government authorized private ships to attack and capture enemy merchant vessels, with the proceeds divided between the Queen and the crew of the privateer. When the war ended, Teach was faced with the prospect of losing his livelihood and the great potential for adventure and profit that it promised. Along with many others in the same position, he turned to piracy.

Teach served for several years on a pirate ship under another captain before, in 1717, he stole a ship for himself and formed a crew of his own. Teach and his crew, aboard the “Queen Anne’s Revenge,” captured a number of valuable cargoes off of the coasts of Virginia and the Carolinas. In what would become one of his most famous acts, Teach sailed boldly into Charleston, South Carolina, captured several prominent citizens, and held them hostage until the city agreed to exchange them for costly medical supplies.

While he was terrorizing commercial ports along the coast of North America, Teach became known as “Blackbeard” and his reputation spread quickly. Blackbeard was widely feared for his violence and cruelty and cultivated a fierce appearance to intimidate his victims. This memorable description is from Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates, published in London in 1726:

This Beard was black, which he suffered to grow of an extravagant Length; as to Breadth, it came up to his Eyes; he was accustomed to twist it with Ribbons, in small Tails, after the Manner of our Ramilies Wiggs, and turn them about his Ears: In Time of Action, he wore a sling over his Shoulders, with three Brace of Pistols, hanging in Holsters like Bandaliers; and stuck lighted Matches under his Hat, which appearing on each Side of his Face, his Eyes naturally looking fierce and wild, made him altogether such a Figure, that Imagination cannot form an Idea of a Fury, from Hell, to look more frightful.

Between adventures at sea, Blackbeard often returned to North Carolina. The shallow waters and complicated inlets of the Outer Banks provided a popular hiding place for pirates while they rested their crews and repaired their ships. Blackbeard favored Ocracoke Inlet and was rumored to have had a house in Ocracoke village. There is an inlet there today still known as “Teach’s Hole.” North Carolina was also a popular refuge for pirates because of its governor, Charles Eden, who was widely rumored to have ignored the illegal activities of the pirates in exchange for a share of the spoils. In the summer of 1718, Blackbeard lived in the coastal town of Bath, North Carolina, where he was known to have socialized with Governor Eden. After a few months on shore, Blackbeard had to return to piracy in order to maintain his lavish lifestyle. The people of North Carolina, tired of seeing their ships attacked and goods stolen, and frustrated at their own government’s failure to act, turned to the governor of Virginia for help.

Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia gathered a crew of British Naval officers, led by Lieutenant Robert Maynard, and sent them to Ocracoke where Blackbeard was known to be hiding. In a fierce fight beginning at dawn on November 22, 1718, the British sailors attacked and defeated Blackbeard and his crew. After suffering twenty-five wounds, including five from gunshots, Blackbeard finally died. Lieutenant Maynard, needing proof of Blackbeard’s death in order to claim the bounty offered by Governor Spotswood, beheaded the pirate and hung his severed head from the front of the ship as it sailed home.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Clowse, Converse D. “Teach, Edward.” In American National Biography, ed. John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Lee, Robert E. Blackbeard the Pirate: A Reappraisal of His Life and Times. Winston-Salem, N.C.: John F. Blair, 1974.

Lee, Robert E. “Blackbeard the Pirate.” In Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, vol. 1, ed. William S. Powell. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979.

Moore, David D. “A General History of Blackbeard the Pirate, the Queen Anne’s Revenge and the Adventure.” Tributaries, vol. 7, 1997, pp. 31-35. Available online, http://www.ah.dcr.state.nc.us/qar/rcorner/genhistory.htm

Rankin, Hugh F. The Golden Age of Piracy. Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg, 1969.

Rankin, Hugh F. The Pirates of Colonial North Carolina. Raleigh: State Department of Archives and History, 2008.