This Month in North Carolina History

At dawn on the first of October 1864 the body of Rose O’Neal Greenhow washed ashore in the surf near Fort Fisher in North Carolina. Perhaps the most famous spy of the Confederate States of America had died as dramatically as she lived.

Rose was born in 1813 or 1814 into a planter family in Maryland. Her father, John O’Neal, was murdered by one of his slaves in 1817. His widow, Eliza O’Neal, was left with four daughters and a cash-poor farm to manage. In part to help family finances, Rose was sent, in her mid-teens, to Washington, D. C. along with her sister Ellen to live with their aunt, Maria Ann Hill. Mrs. Hill and her husband managed a highly regarded boarding house across from the U. S. Capitol. The house was often referred to as the “Old Brick Capitol” since it originally had been built as the temporary meeting place of Congress after the Capitol had been burned in the War of 1812. Pretty, lively, and intelligent, Rose was popular with the members of Congress who boarded with her aunt, and she had several suitors. In 1835 she married Robert Greenhow, a wealthy bachelor who had trained as a physician but ultimately became an official in the United States Department of State. In addition to bearing a large family, Rose became an important figure in Washington society. She was charming, witty, politically astute, and a fervent champion of the southern states in the increasingly bitter sectional struggles of the 1840s and 1850s. The death of Robert Greenhow in 1854 left Rose financially stretched, but she continued her association with important national political figures, particularly President James Buchanan. Rose considered the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 to be a national disaster and whole-heartedly supported secession and the newly formed Confederacy.

Sometime in 1861 Rose Greenhow was recruited as a spy for the Confederacy. She quickly formed a network of agents from among her Washington circle of Confederate sympathizers and began enthusiastically and efficiently gathering information about the Union Army camped around the capital, which she transmitted to General P. G. T. Beauregard who commanded Confederate forces in nearby Virginia. Rose charmed information from important beaureaucrats, army officers, and politicians including, it was rumored, a Republican senator who sent her passionate love letters. She gave Beauregard the date on which the Union Army would began its advance on his position in 1861 and was credited by him with an important contribution to the subsequent victory at the battle of Manassas. Rose refused, however, to become the stereotypical spy who blends in with her background to escape detection. She continued vigorously to defend the southern cause and lambast Republicans. After Manassas she began to come under suspicion. She was arrested in August of 1861 and held for the next year and nine months without being charged or brought to trial. Rose was hardly a model prisoner, reviling her guards, complaining about her treatment and generally making herself a thorn in the side of the Lincoln government. At the end of May 1863 she was exiled to the Confederacy.

Rose Greenhow was given a heroine’s welcome in Richmond and thanked personally by President Jefferson Davis for her aid to the Confederacy. Davis also took the unprecedented step of asking Rose to promote Southern interests in England and France as his personal, if unofficial, representative. In August 1863 Rose and her youngest daughter, also named Rose, sailed on a blockade runner from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Bermuda where she booked passage to England. Rose was warmly greeted by many in the English aristocracy who sympathized with her and her cause. Over the next year she spoke with a number of leaders of British politics and society including Thomas Carlyle and Lord Palmerston. She was granted an audience by Napoleon III of France and visited with southerners who had taken up residence abroad. A British publishing house brought out her memoir, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolitionist Rule at Washington, which was a success.

In August 1864 Rose returned to America, convinced that she could do nothing to persuade the British or French governments to recognize the Confederacy. On the last night of September her ship, the blockade runner Condor approached the mouth of the Cape Fear River on the run to Wilmington. It was spotted by a U. S. naval vessel early on the morning of October 1st and ran aground trying to escape. Rose was carrying dispatches for President Davis and her book profits in gold coins in a leather bag around her neck. She demanded that the captain set her ashore immediately, although he tried to convince her that the ship was safe under the guns of Fort Fisher until she floated off the shoal. In the end Rose had her way and with several other people was launched in a boat for the shore which was only a few hunded yards away. Within minutes the small boat capsized. Rose sank out of sight immediately while the others clung to the overturned boat and ultimately survived. Her body was buried in Wilmington, North Carolina.

Sources

Blackman, Ann. Wild Rose: Rose O’Neale Greenhow, Civil War Spy. New York: Random House, 2005.

Ross, Ishbel. Rebel Rose: Life of Rose O’Neal Greenhow, Confederate Spy. New York: Harper, 1954

Greenhow, Rose O’Neal. My Imprisonment and the first year of Abolition Rule at Washington. London: R. Bentley, 1863.

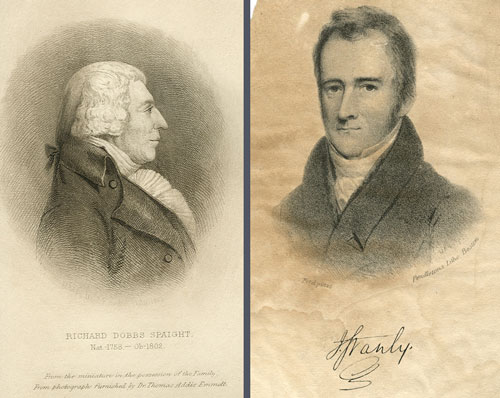

Image Source:

“Mrs. Greenhow and the Two Other Passengers Demanded to be Set Ashore.”

Half-tone plate engraved by C.E. Hart from a drawing by Stanley M. Arthurs.

In Harper’s Monthly Magazine, March 1912, p. 575.

“While there may be some question as to who should be regarded as the greatest North Carolinian, certainly in a list of the five greatest, the name of George E. Badger should be included.”

“While there may be some question as to who should be regarded as the greatest North Carolinian, certainly in a list of the five greatest, the name of George E. Badger should be included.” Whenever we walk through the county history section in the North Carolina Collection, one book always catches our eye. Most hardcover books used to be bound in cardboard which was then covered with cloth (many still are today, though more and more publishers go simply with the board covers). When it came time to bind Walter Whitaker’s Centennial History of Alamance County, 1849-1949, they probably didn’t have to think very hard about what kind of cloth to use.

Whenever we walk through the county history section in the North Carolina Collection, one book always catches our eye. Most hardcover books used to be bound in cardboard which was then covered with cloth (many still are today, though more and more publishers go simply with the board covers). When it came time to bind Walter Whitaker’s Centennial History of Alamance County, 1849-1949, they probably didn’t have to think very hard about what kind of cloth to use.