As is befitting the two oldest state universities in the country, the football rivalry between UNC and the University of Georgia goes back more than a century, with the teams first meeting in Alanta, site of this year’s game, in 1895 (100 years after UNC began offering classes and 94 years after the University of Georgia opened). Carolina won the first game, held on October 26, 1895, 6-0, and followed that with another win over Georgia just five days later.

One of Carolina’s biggest wins against Georgia came in 1914. UNC won 41-6 in a dominating performance. The Tar Heel could not resist multiple references to William Sherman’s march through Georgia, which was a not-so-distant memory, having occurred only fifty years earlier:

About fifty years ago one General Sherman with an army of blue coated men marched through Georgia. Last Saturday a squad of men led by Head Coach Trenchard and Capt. Tayloe, both marched and ran through Georgia. In the sixties the march was attended by slaughter and devastation of human life; last Saturday the march was also accompanied by slaughter and devastation — this object being this time the destruction of Georgia’s hopes for a Southern conference championship in football.

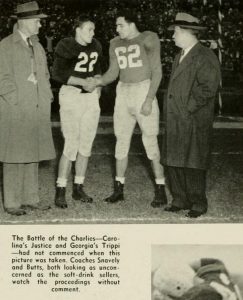

Carolina and UGA did not meet again for 15 years. The two schools played fairly frequently from the 1930s through the 1960s, with the most notable matchup coming in the 1947 Sugar Bowl. The Sugar Bowl game, won by Georgia, 20-10, featured two legendary players: UNC’s Charlie Justice and Georgia’s Charlie Trippi.

From 1967 to 1977, the UNC and Georgia teams were coached by brothers: Bill Dooley, who led the Tar Heels, and his older brother Vince, who coached the Bulldogs. The last game between the schools was also the only one coached by the two brothers. UNC and Georgia met in the 1971 Gator Bowl, with Georgia winning 7-3. Following the close game, Vince Dooley said, “I think my brother Bill outcoached me,” leading to the ironic Daily Tar Heel headline: “Gator Bowl: Bill Wins, Heels Lose.”

UNC and Georgia have played 30 times, with the Bulldogs winning 16. The last UNC victory over Georgia came in Chapel Hill in 1963.