Following the recent decision remove Charles Brantley Aycock’s name from an auditorium at UNC-Greensboro, which followed similar moves last year at East Carolina and Duke, we took a look to see what we could find in University Archives related to … Continue reading →

Following the recent decision remove Charles Brantley Aycock’s name from an auditorium at UNC-Greensboro, which followed similar moves last year at East Carolina and Duke, we took a look to see what we could find in University Archives related to the naming of Aycock Residence Hall at UNC.

It didn’t take long for somebody to suggest naming a building at UNC after Charles Brantley Aycock. Just a couple of weeks after the former governor died in 1912, the President of the newly-formed Aycock Memorial Association wrote to UNC President Francis Venable: “There is no educational memorial which could be more fitting than a building at the University.” [University Papers, 20 April 1912]

It would be another sixteen years before UNC named a building for Aycock. During a period of rapid expansion in the 1920s, the university completed four new dorms in 1924. Known for several years simply as “New Dorms,” they finally received names in 1928. The Board of Trustees reported on the names in the minutes from their June 11, 1928 meeting:

“Mr. [John Sprunt] Hill for the Building Committee recommended that the policy be adopted in naming teachers’ buildings for great teachers and dormitories for other distinguished citizens; further that the new class-room building be named ‘Bingham Hall’ and the four new dormitories for Chas. B. Aycock, John W. Graham, W.N. Everett and Dr. R.H. Lewis and that the new library be named ‘The University Library.’ On motion, the above recommendations were adopted.”

That’s about it. There was only a passing mention of the naming in the Daily Tar Heel and nothing that we could find in the University Papers, where most of the early correspondence of the president of the university is held. It is not that unusual that there is nothing in the administrative correspondence; then, as now, the Board of Trustees had the final say on building names at UNC.

Given the strong feelings about Aycock both at UNC and statewide, it’s a little surprising that it took so long to name a building in his honor. In 1904, President Venable wrote to Governor Aycock asking him to consider accepting an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from UNC (Aycock initially refused, but would receive the honor a few years later). Venable wrote, “In the twenty-five years I have spent in the State, I know of no one who has so served her highest interests as you have, and the influence of your administration will be felt for a long time to come.”

Venable was hardly alone in his praise. After Aycock died in 1912, the UNC Board of Trustees passed a resolution in honor of Aycock’s work on education:

“The Board of Trustees desire to place on record their deep sense of loss in the death of Ex Governor Charles B. Aycock, who as a member of this Board and of the Executive committee rendered most efficient service and attested his love for the University. During his administration as Governor, the cause of education was greatly advanced in this state and at all times he was ready to give encouragement to those who were striving to uplift this cause in the South and ended his life with a plea for the education of the child. He gave his best efforts in service for others, and while we will miss his companionship and wise advice, his memory will remain to urge us to follow the example which he has left of striving to do good to those who most need the benefit of Education. To his widow and family we extend our sincere sympathy and request our President to communicate to them this tribute of respect and direct the same to be entered on our minutes.”

The views of the Board of Trustees at the time were shared by many white leaders around the state. Aycock did support public education, but ensured that substantially more support would go toward schools for white students. The Trustees would not have found this unusual; they were overseeing an institution that strictly prohibited African American students from attending and had only just begun experimenting with allowing women to enroll.

Neither the note from Venable or the Board of Trustees resolution mention Aycock’s prominent role during the Democratic Party’s 1898 white supremacy campaign, nor do they note his strong support for a constitutional amendment in 1900 that effectively disenfranchised nearly all African American voters in the state. The prevailing view of Aycock in the media at the time — it is often reflected in the Daily Tar Heel — was of a benevolent “education governor.” We did not find anything in the contemporary statements from UNC leaders reflecting on other aspects of Aycock’s legacy.

Our quick look into the archives did not, by any means, uncover everything related to Aycock and UNC. He had a long relationship with the university, first as a student, later as a prominent alumnus, and then a three-time member of the Board of Trustees. Students and researchers who wish to dig deeper can find a significant amount of correspondence to and from Aycock in the University Papers as well as in manuscript collections in the Southern Historical Collection.

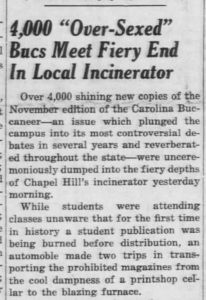

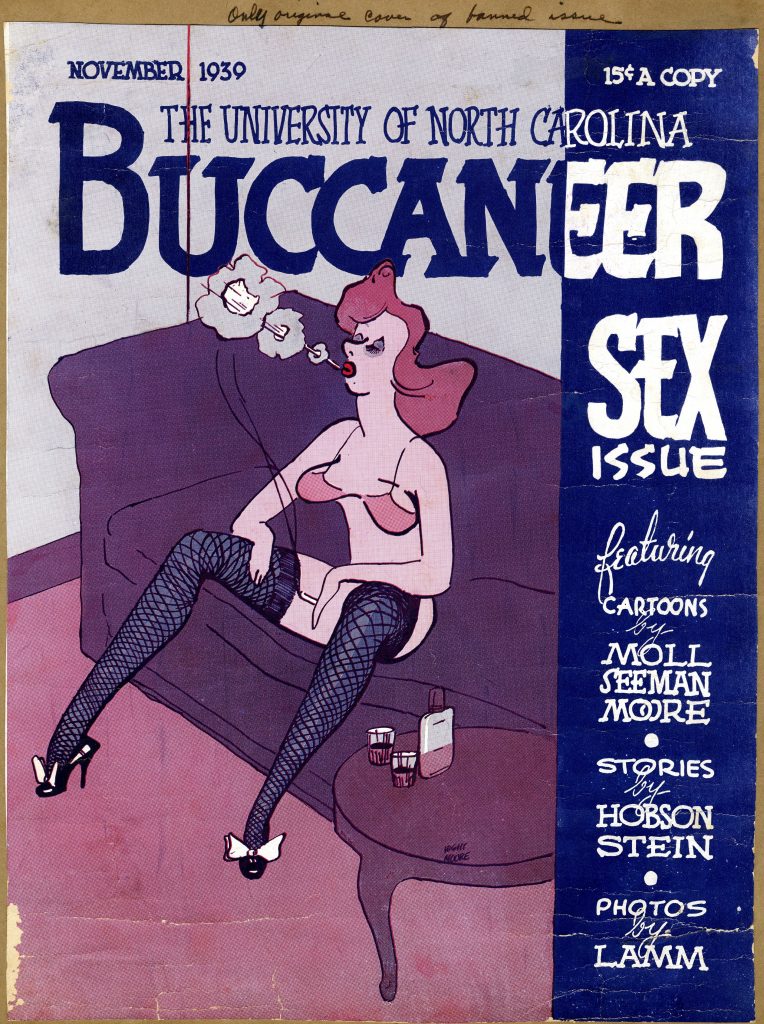

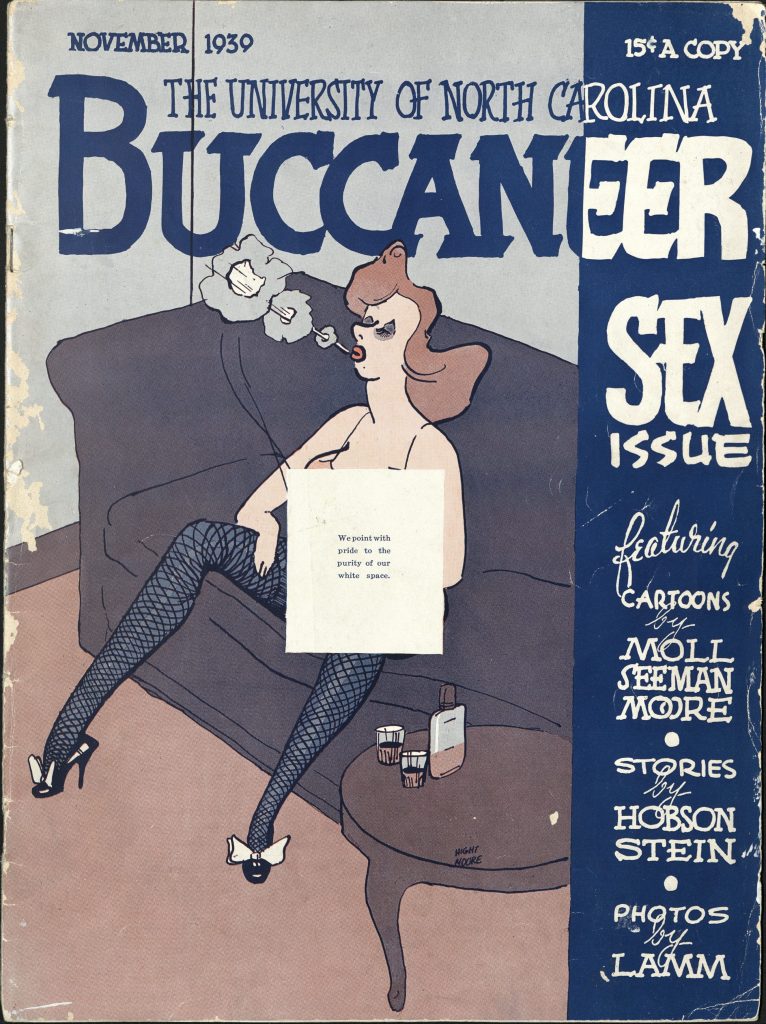

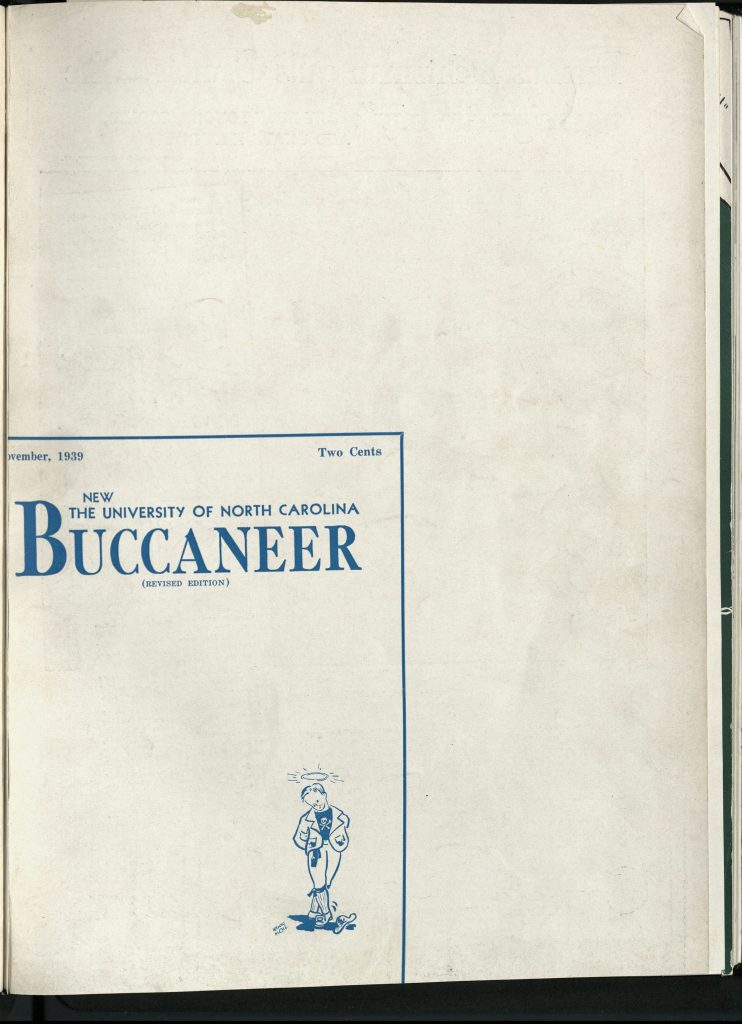

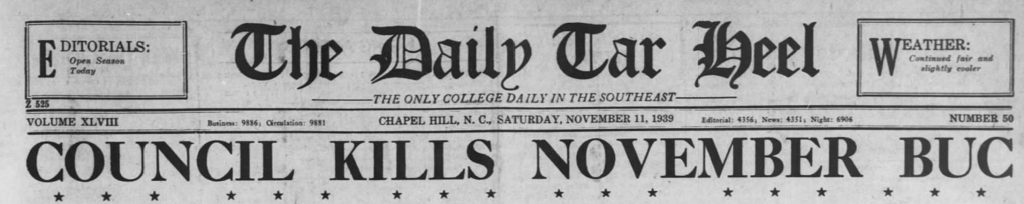

The combination of scandalous content and official censorship makes the story of the 1939 Carolina Buccaneer “Sex Issue” one of the most intriguing in UNC history.

The combination of scandalous content and official censorship makes the story of the 1939 Carolina Buccaneer “Sex Issue” one of the most intriguing in UNC history.