In the wake of the recent protests and demonstrations at the University of Missouri, many people in the UNC community are looking back on our own past at occasions where students and activists fought for change in Chapel Hill. Two … Continue reading →

In the wake of the recent protests and demonstrations at the University of Missouri, many people in the UNC community are looking back on our own past at occasions where students and activists fought for change in Chapel Hill. Two pieces published today — an article in the Daily Tar Heel and an excellent blog post by graduate student Charlotte Fryar — draw comparisons between Missouri and a specific series of protests at UNC in 1992.

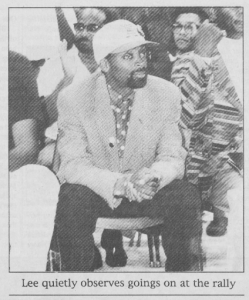

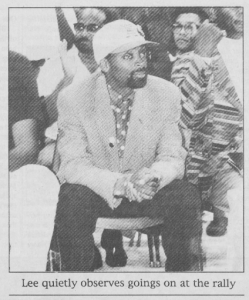

Spike Lee at UNC, 17 September 1992.

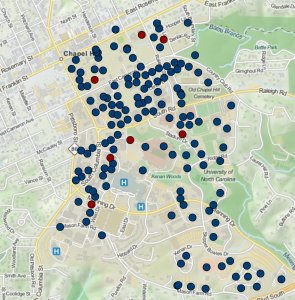

Students at UNC rallied throughout the spring and fall of 1992 in support of several issues, most notably the construction of a freestanding Black Cultural Center on campus. The protests drew national attention and filmmaker Spike Lee came to campus to help rally the students and support their cause. By at least one measure, the protests were a success: after repeatedly speaking out against a separate Black Cultural Center on campus, Chancellor Paul Hardin eventually endorsed a plan to build the center, and agreed to name it after former UNC faculty member Sonja Haynes Stone.

There is a lot of information about the protests and the reactions of the administration in the University Archives and other Wilson Library collections. This general guide to sources and basic timeline of the events will serve as a starting point for students and others interested in learning more about this important period in UNC history.

General Sources

- The Daily Tar Heel covered all of the major protests and administrative actions related to the debate over the Black Cultural Center. Digitized copies are available on newspapers.com. Access to the digitized DTH is available without charge on campus and to anyone with a current Onyen.

- Black Ink, the newspaper of the Black Student Movement, provided extensive coverage of the protests and student reactions. Digitized copies of the paper are available through the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center.

- Regional media, especially the News and Observer in Raleigh, covered many of the student protests. The Wikipedia article on the Sonya Haynes Stone Center has an excellent list of citations to relevant newspaper articles.

- The Records of the Office of the Chancellor at UNC, Paul Hardin Records (1988-1995), include several folders related to the Black Student Movement and student protests. One of these folders, containing correspondence and clippings related to the protests, has been digitized.

- The Carolina Alumni Review, Winter 1992 issue (vol. 81 no. 4) includes a lengthy article about the protests, the long movement toward a Black Cultural Center, and a “Chronology of Racism Issues at UNC.”

Timeline

24 February 1992: Students from the Black Student Movement, Campus Y, and other student activists issue several demands to Chancellor Paul Hardin: the construction of a freestanding Black Cultural Center on campus, named after Sonja Haynes Stone; and endowed faculty position named after Sonja Stone; and action by the University to improve pay and working conditions for housekeepers on campus. [Source: DTH, 2/25/1992]

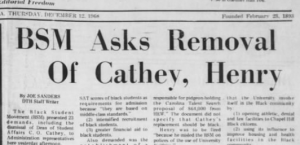

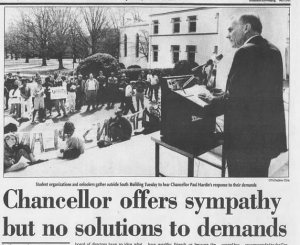

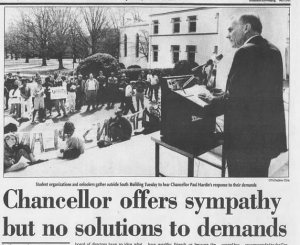

Daily Tar Heel, 18 March 1992

17 March 1992: Hardin responds to the student demands in remarks delivered at South Building. Hardin expressed his sympathy with student requests, but said he was unable to meet any of them. He said, “I do not agree with those of you who advocate a free-standing Center.” [Sources: DTH, 3/18/1992; the full text of Hardin’s response is available in the Chancellor’s records in University Archives — digitized copy here, beginning with scan number 35]

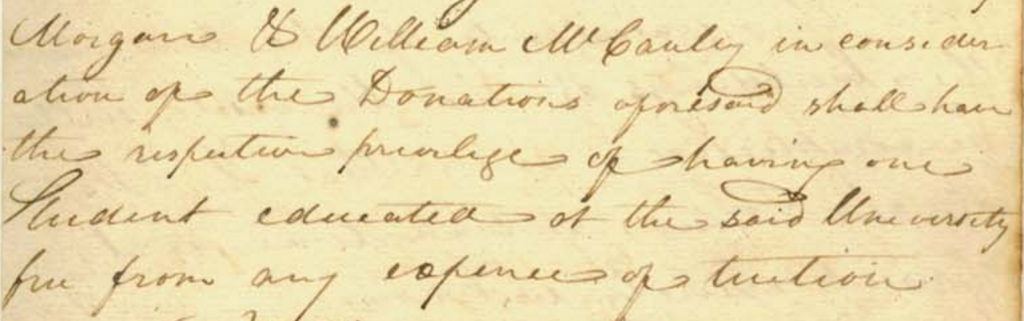

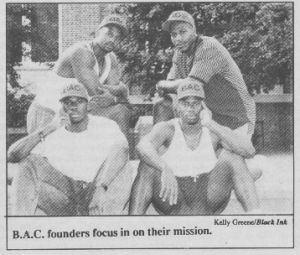

Black Awareness Council founders. From Black Ink, 8/31/1992.

Early Summer 1992: Four African American football players — John Bradley, Jimmy Hancock, Malcolm Marshall, and Timothy Smith — form the Black Awareness Council, a group dedicated to increasing awareness among African Americans about campus and community issues. The founders spoke about their desire to get black athletes more involved in issues of importance to other black students on campus. [Source: Black Ink, 8/31/1992]

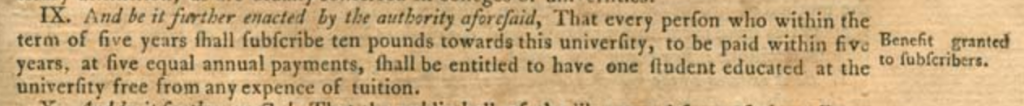

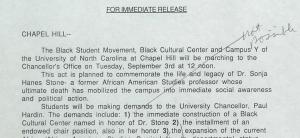

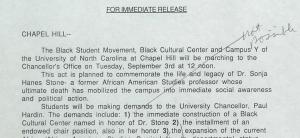

30 August 1992: The Black Student Movement, Campus Y, and Black Awareness Council list their demands and announce a plan to bring them directly to Chancellor Hardin at his home. [Source: Records of the Office of the Chancellor; the digitized statement shows Hardin’s handwritten note, “Not possible” next to the demand for a freestanding Black Cultural Center]

3 September 1992: Around 300 students march to Chancellor Paul Hardin’s house demanding immediate action on their demands. [Sources: DTH, 9/4/1992); Black Ink, 9/16/1992]

Announcement of student demands with Chancellor Hardin’s handwritten annotations.

10 September 1992: Several hundred students march to South Building to present a letter from the Black Awareness Council demanding both support and a clear plan for building a separate Black Cultural Center on campus. The students give the Chancellor a deadline of November 13. They write, “Failure to respond to this deadline will leave the people no other choice but to organize toward direct action.” The protest draws the attention of the New York Times, which resulted in an article the following day. [Source: DTH, 9/11/1992].

17 September 1992: Moved by what he has read about the student protests, filmmaker Spike Lee comes to campus to lend his support. Around 5,000 students hear him speak at the Dean Dome. Lee draws attention to the fact that African American athletes are active in leading the protests. He says, in an interview with Black Ink, “What’s important here is that the athletes are at the vanguard of this. The reason why that is important is that college sports is powered by the muscle, brawn, speed, and intelligence of the black athletes. If these schools didn’t attract black athletes through football and basketball, there could be no multimillion dollar T.V. contracts.” [Source: Black Ink, 10/5/1992].

23 September 1992: Provost Richard McCormick forms a panel to investigate and come up with a plan for an expanded Black Cultural Center on campus. [Source: DTH, 9/24/1992].

1 October 1992: An article in the Daily Tar Heel discusses the involvement of football players in the protests and addresses the prospect of players missing practices or games. Tim Smith, one of the founders of the Black Awareness Council, says, “BAC hasn’t said anything about (boycotting), so it’s not an issue.” Football coach Mack Brown is quoted as saying he has encouraged the players to be active on campus, but, “We’ve always asked them to do it as an individual and not as representatives of our football program.” [Source: DTH, 10/1/1992, p. 7]

5 October 1992: The panel votes, 10-2, in favor of a freestanding Black Cultural Center. [Source: DTH, 10/6/1992]

12 October 1992: Still awaiting a response from Chancellor Hardin, about 125 students briefly interrupt University Day festivities to advocate for the Black Cultural Center. [Source: DTH, 10/13/1992]

15 October 1992: Chancellor Hardin announces his support for a freestanding Black Cultural Center on campus: “I endorse a free-standing facility to house the center and will recommend that the proposed facility be named for Dr. Stone.” [Source: DTH, 10/16/1992]

As we find other relevant sources, we’ll update this blog post. For more information or suggestions for exploring this or other topics on UNC history, contact or visit Wilson Library.

Photographs, news ads and articles, excerpts from student handbooks, and nearly 60 clothing items tell the story of student life as reflected in a century of style. Continue reading

Photographs, news ads and articles, excerpts from student handbooks, and nearly 60 clothing items tell the story of student life as reflected in a century of style. Continue reading