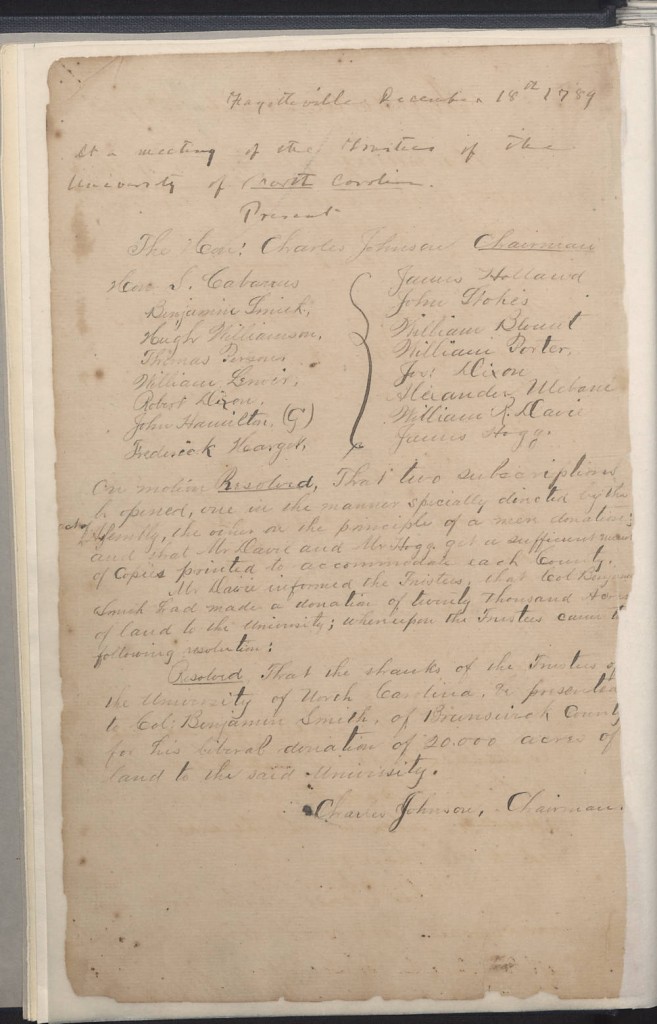

Prologue:

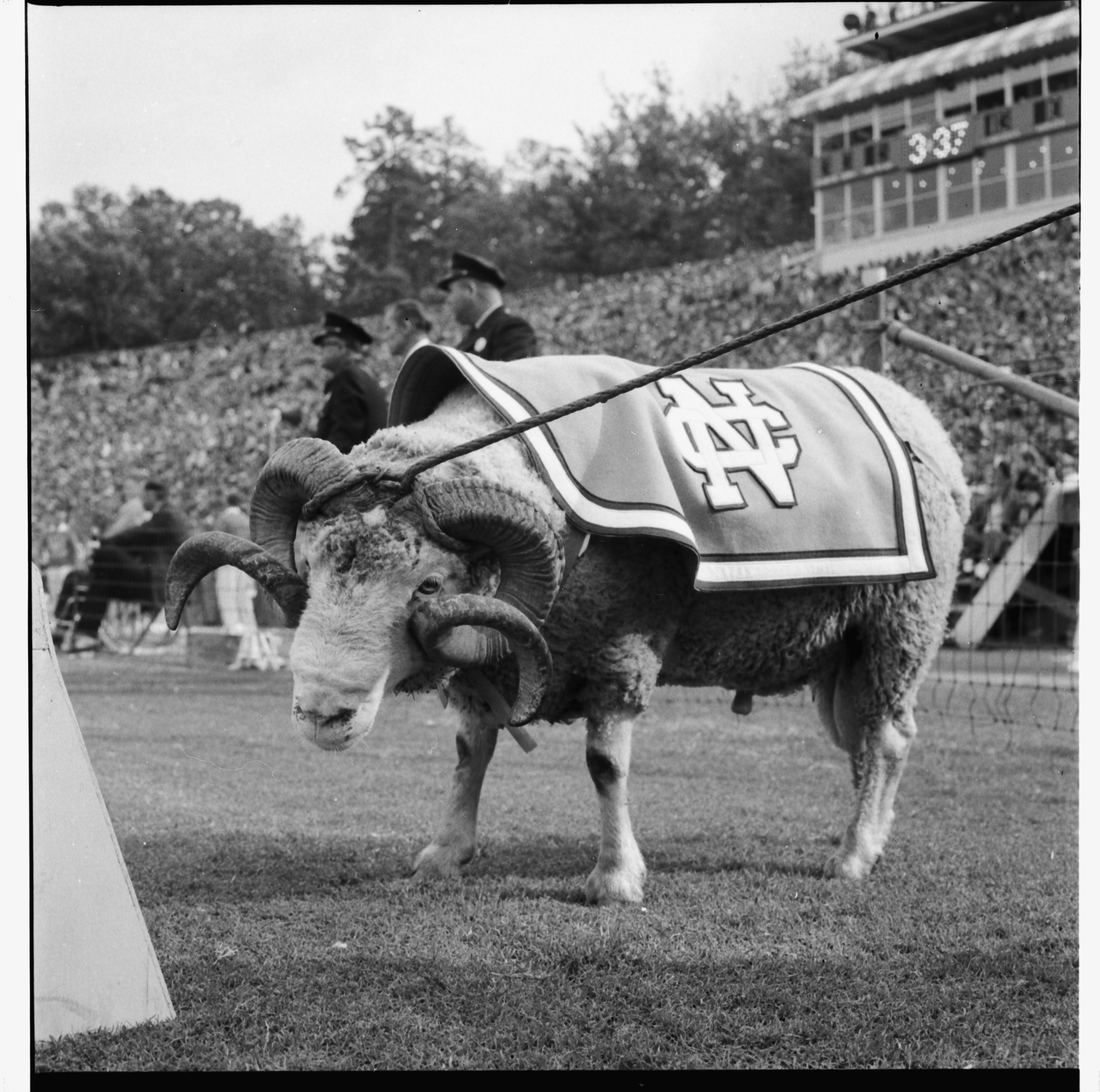

Duke University play-by-play broadcaster Bob Harris called Charlie Justice “the greatest player to ever wear the Carolina colors.” During the “Charlie Justice Era” those colors were navy blue in 1946 and ’47 and Carolina Blue after that, but there was always a thread of royal blue that ran through Charlie’s life and career.

“Justice Always At Best Against Duke”

—Greensboro Record headline, Thursday, November 17, 1949

Introduction:

Carolina will play Duke on the gridiron for the 100th time today, November 30, 2013. Over the years, that match-up played a part in the life and times of Tar Heel legend Charlie Justice. It was twelve seasons ago, during Carolina–Duke weekend, that Justice made what turned out to be his final visit to Kenan Stadium. The events of that weekend are the stuff of legends. In keeping with this holiday weekend’s theme of UNC football rivalries, Morton volunteer/contributor Jack Hilliard takes a look back at the thread and the final visit.

Note: to see a plethora of UNC versus Duke football photographs by Hugh Morton, you may search both “UNC vs. Duke football” and “UNC v. Duke football” (until I get a chance to change the title for all photographs to the former!) in the online collection of Morton photographs.

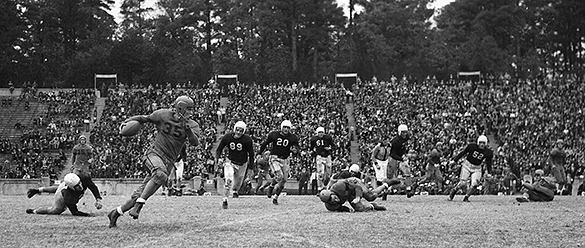

Action during the UNC-Chapel Hill vs. Duke University football game at Duke’s Wallace Wade Stadium, Durham, N.C, November 24, 1973. UNC players: #61 Offensive Guard Billy Newton and #40 Halfback Jimmy Jerome. Duke players: #62 Linebacker Dave Meier, #24 Defensive Safety Buster Cox, #76 Defense Tackle John Ricca, and #45 Linebacker Keith Stoneback.

It was not surprising that Charlie Justice made his final visit to Kenan Stadium during a Carolina–Duke football game. The Justice–Duke connection runs through his life going back to his high school days at Lee Edwards High in Asheville. When Justice and his Lee Edwards High teammates finished the 1942 football season, they had a 26 and 6 won-lost record and had scored 939 points while their opponents had scored only 159 during their three seasons together. The folks at Duke University invited the entire team to visit the campus and attend a football game. Duke Head Coach Eddie Cameron seemed interested in the entire team, but knew each young man was also being recruited by that “other big four”—Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force. Justice liked what he saw at Duke, but knew it would be at least three years before he would be available to think about college.

In the spring of 1943, Justice enlisted in the Navy, which sent him to Bainbridge Naval Training Center in Bainbridge, Maryland. On August 7, 1943, the base newspaper, The Mainsheet listed on the front page an “urgent call” for football players. Bainbridge was planning for its first football team. Justice reported, but wasn’t given a second look because he had only high school experience while most of the other players had college and professional backgrounds. It didn’t take long, however, for him to be noticed in a big way. Bainbridge head coach Joe Maniaci called him “the greatest natural football player I’ve ever seen.” Justice led the Commodores to undefeated seasons in 1943 and 1944. In an interview in The Baltimore Sun on October 18, 1944, Justice indicated his future plans by saying, “it’s Duke for me.” Needless to say, Coach Cameron was delighted.

Following the 1944 season, Justice was transferred to Pearl Harbor and played the 1945 season with the Pacific Fleet All-Stars. It was there where he became good friends with teammate George McAfee, who had played at Duke from 1937 to 1939.

After the ’45 season, Justice called his wife Sarah and told her he would be coming home in early January. “Please, please don’t tell anyone I’m coming. I want this vacation to be ours. It’s real flattering, but these college scouts are on me everywhere I turn,” said Justice. The train ride from San Francisco to Asheville was long and tedious, but finally he was home. As he exited the Pullman, there stood a fellow with a wide smile and thinning red hair. It was Charlie’s old Asheville friend Dan Hill, who was now the assistant athletic director at Duke. “Dan Hill, what the blazes are you doing here?” asked Justice.

“Why, you know what I’m here for,” said Hill. “We want you to attend Duke, Charlie. We’d like you to play a little football for us, too.”

Charlie begged off an immediate commitment, located Sarah, and headed home.

Justice still had an interest in Duke, and later set up a visit to the Duke campus. Wallace Wade had since returned to Duke and was to be the new head coach. During a conversation with Coach Wade, Justice said, “Coach, I played over at Pearl Harbor with one of your boys who was one of the greatest players I’ve ever seen.”

“Who was that?” Wade asked.

“George McAfee,” said Justice.

“George McAfee wasn’t a football player. Steve Lach was my kind of football player,” snapped the coach. Lach had also been a star at Duke and was on the team at Pearl Harbor, but didn’t get much playing time.

When the conversation with Coach Wade ended, Charlie and Sarah left. As they were walking to the car, Sarah smiled and said, “I know one thing. We’re not coming to Duke, are we?” She knew how Charlie admired George McAfee.

Charlie looked her in the eye. “That’s the truth. We’re not coming to Duke.”

In an interview in the November, 1949 issue of Sport, Charlie’s mom said, “Duke made the best offer. Wallace Wade and Dan Hill said they would not make a flat offer, but would do anything anyone else would. But Charlie didn’t want to play for Coach Wade.”

Author Lewis Bowling, in his excellent 2006 book, Wallace Wade: Championship Years at Alabama and Duke, wrote:

It is known that Duke had A-1 priority while Charlie was romping to high school touchdowns. The Navy engulfed him, however, and when he emerged was perhaps the most sought-after service athlete in the country. Married and discharged, Justice went to see Dan Hill first. He told Dan what he wanted. Dan told Duke, and Duke told Charlie, ‘You-funny-boy-you.’

During an interview in July of 1984, I asked Charlie what he asked of Duke. He said, “I asked the same question at Duke that I asked at Chapel Hill. Since I was eligible for the GI Bill, I asked if my football scholarship could be transferred to my wife. Duke said no, but Robert Fetzer, the athletic director at UNC said he would check with the NCAA and the Southern Conference to make sure it would be OK.” Turns out it was, and the Justices enrolled at UNC on February 14, 1946.

Charlotte Observer sports editor Wilton Garrison, writing in the October 1947 issue of Sport, described Charlie’s first encounter with Duke on the gridiron:

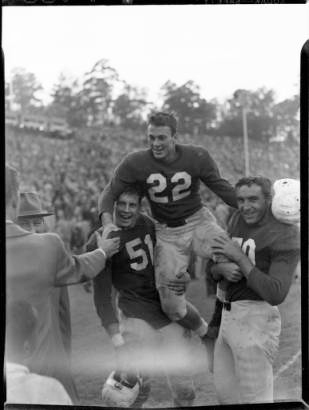

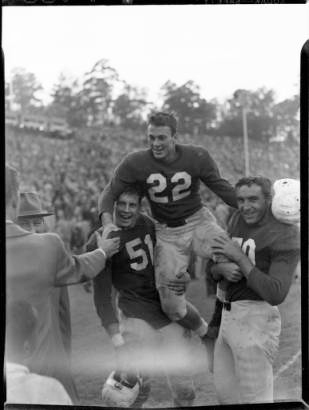

Sarah Justice loves football. She sat in Kenan Stadium the afternoon of November 23, 1946, and celebrated her third wedding anniversary by watching the whole Duke Foundation fall upon her husband. But when they removed the rubble from her darling he was still in one piece, able to ride piggy-back on his fellow teammates as they walked off the field with a 22 to 7 victory.

Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice (#22) being carried by his teammates, UNC-Chapel Hill versus Duke University football game, at Kenan Memorial Stadium, Chapel Hill, N.C., November 23, 1946.

Said Coach Carl Snavely following the ‘46 game, “I don’t think that Charlie Justice has played a better game all year than he did today.” One of Charlie’s teammates that day was end Ed Bilpuch who would later become a Professor of Nuclear Physics at Duke.

The following year in Durham, Justice was involved in all three of Carolina’s touchdowns as the Tar Heels won, 21-0. The Alumni Review headline read: “Duke Outclassed, Outplayed, Outscored.”

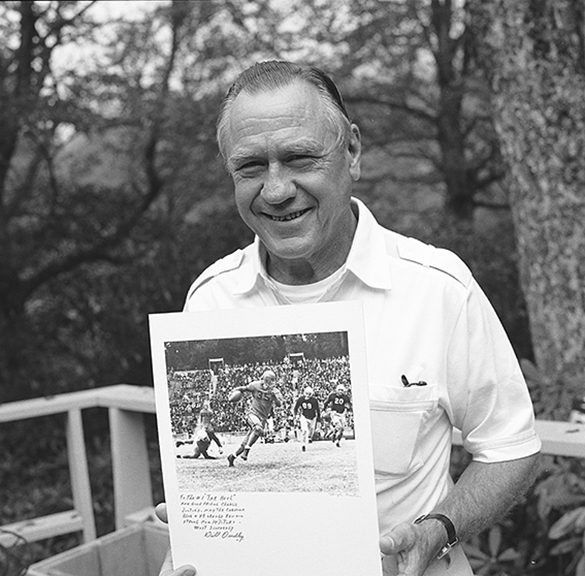

Charlie’s 43-yard touchdown run in the 1948 UNC – Duke game is one of the most talked-about plays in Tar Heel history. The play broke open a game that was tied and opened the flood gates for a 20 to 0 win.

A few days before the ’49 UNC vs. Duke game, Justice received the first pressing of the recording “All The Way Choo Choo,” from band leader Johnny Long, a Duke graduate, class of 1935. That 1949 Carolina–Duke game has often been called the greatest game in North Carolina sports history. 57,500 fans in Duke Stadium (now Wallace Wade Stadium) saw Carolina win a thriller 21 to 20. Duke was led by Billy Cox and Carolina was led by Charlie Justice. Cox and Justice would reunite with the Washington Redskins in 1952.

Following each of Carolina’s four wins during the “Justice Era,” Duke Head Coach Wallace Wade would was always quick to praise the Tar Heel team, but didn’t mentioned Justice or any Tar Heel by name. This quote is from November 23, 1946 is typical: “It is obvious that they completely outplayed us. I would like to pay great praise for a great team.” Nine days after the ’49 Duke – UNC game, on Tuesday, December 2nd, Coach Wade and Justice were both guests at the Sanford (N.C.) Quarterback Club dinner and Wade broke his silence about Charlie Justice. Said Wade: “No man during my career as a coach has had the degree of success against my teams throughout his career that Charlie Justice has had.”

When Carolina met Duke for the 50th time on November 21, 1964, Hugh Morton brought his young daughter, Catherine, to the game with him. Hugh and Catherine were guests in the chancellor’s box, next to the UNC press box at Kenan Stadium. Hugh didn’t remain in the chancellor’s box very long. He took his familiar place on the Carolina sideline with camera in hand. As the game got underway, young Catherine looked around and noticed that most of the guests were socializing and not really paying attention to the game as she was. However, there was one other gentleman watching the game and he came over and asked Catherine if she understood what was going on down on the field. When she said “no,” he offered to explain the game and remained with her until her father returned. So Catherine Morton these days says that she learned about “first downs and fourth downs” from “the nice gentleman” in the chancellor’s box that day: Charlie Justice. He most likely used his parenting skills that afternoon. (Both of Charlie’s children—Ronnie in 1948 and Barbara in 1952—were born at Duke Hospital).

The Justice-Duke connection continued when the Tar Heels met the Blue Devils in 1978. Justice listened to the game on the radio at his home. He was recovering from a heart attack. On October 22, 1978, Justice was in Rockingham, N.C. where he was to be the Grand Marshall of the American 500 NASCAR race. But in the early morning hours he suffered his second heart attack. At 10 am on November 14, 1978, he had open heart surgery at Duke University Medical Center, of all places. He would later say, “that’s probably the best place for me to have serious surgery . . . you don’t think they would let me die on their watch do you?” He fought and won his biggest battle, and on Thursday, November 23rd, Justice was able to go home to Greensboro and celebrate his 35th wedding anniversary.

Two days later, Carolina met Duke for the 65th time. With four minutes to go, and trailing 15 to 2, Carolina Head Coach Dick Crum called a time out and called his team around him. “We’ve got to win this one, remember, for Charlie Justice.” Crum had told his team following the Virginia game that if they won against Duke, they would sign and give the game ball to Charlie. In the final four minutes, the Tar Heels scored twice and “Famous Amos” Lawrence crossed the goal line with 11 seconds on the clock. The ball that Lawrence carried was put into safe keeping and Coach Crum delivered it to Charlie on Thursday, March 29, 1979 at the Greensboro Kiwanis Club meeting. Said Justice, with a smile “…this is the first game football I ever received at Carolina. My four years we only had two footballs, and coach checked them closely after every game.”

The 1993 UNC – Duke game was played at 11 o’clock on a Friday morning, thanks to ABC-TV. Although their anniversary was November 23rd, Charlie and Sarah celebrated their 50th anniversary at the game on November 26th. Following the game, a reception was held at the Carolina Inn with photographer Hugh Morton documenting every minute.

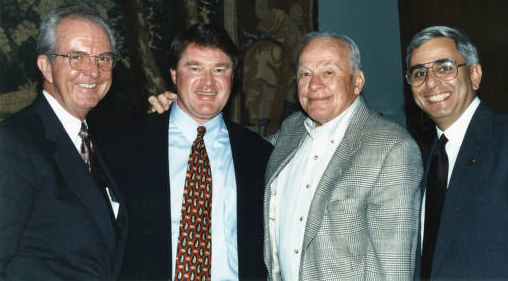

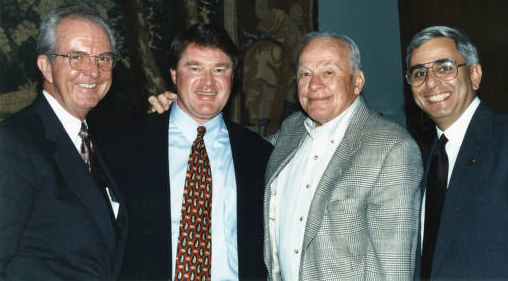

Woody Durham, John Swofford, Charlie Justice, and Dick Baddour at unknown event held at the UNC-Chapel Hill Alumni Center, circa late 1990s to early 2000s.

When Carolina met Duke for the 2001 game, the “Charlie Justice Era” players held one of their reunions. On Friday evening November 16, 2001, the “Golden Age” players gathered at the Kenan Football Center for a special ceremony. On that evening, the first-floor memorabilia room was dedicated and will be forever known as the “Charlie Justice Hall of Honor.” Among those involved were Head Football Coach John Bunting, UNC Chancellor James Moeser, Carolina Athletics Director Dick Baddour, world class photographer Hugh Morton, UNC letter winner Bob Cox (who helped organize the reunion), along with former players, Justice family members, friends and fans. “The Voice of the Tar Heels,” Woody Durham presided over the ceremony. Later that evening he would broadcast his 1000 basketball game on the Tar Heel Sports Network. Justice was there to officially cut the ribbon. “I tell the current players all the time that the foundation of this football program was laid in the 1940s when you guys came here and did what you did,” said Baddour. “We’re standing in the ‘Charlie Justice Hall of Honor.’ It doesn’t get any better than that.” The dedication ceremony was followed by a dinner in the Pope VIP Box at Kenan Stadium.

During halftime of the game on Saturday, Woody Durham came down from his broadcast position to emcee a special ceremony at the 50-yard line. Leaders of the four “Justice Era” teams were driven to midfield in special golf carts. Ralph Strayhorn, Co-Captain in 1946, Joe Wright, Co-Captain in 1947, Art Weiner, All-America in 1948, and Justice, All-America and Captain in 1949. The team members presented Baddour with a check in the amount of one million, three hundred thousand dollars for the “Justice Era Endowment Fund.” The players were then introduced to a standing-ovation from the Kenan crowd. In introducing Justice, Durham simply said, “He was the best.” Charlie then stepped forward and raised his right hand, which was half-closed due his crippling arthritis.

Following the ceremony, Durham returned to his position high above Kenan Stadium and as he looked back on the events of the weekend, he said to his broadcast partner Mick Mixon, “I hope that was not Charlie’s final visit to Kenan Stadium.” During the second half, Coach Bunting was seen several times glancing up at the patio outside his office in the Football Center. That’s where the Justice family was sitting in the warm November sun.

Following the game, Marla and I hurried from our seats in section 220 down to the Football Center, hoping to get a word with Charlie and Sarah before they left. When we arrived, as one might guess, Justice was signing autographs in the lobby. The entire Justice family then came out to the front as team mate Joe Neikirk brought the Justice car up to the door. I remember standing there beside Charlie as he started to enter the car, but then stopped, looked up at the magnificent Kenan Football Center and said, “they didn’t have anything like this when we were here.” He then got in the car and Neikirk drove away.

Hugh Morton, in a post game interview said: “You could start a real argument around here about who is the most exciting basketball player in school history, but if you asked anyone who is the most exciting football player in school history, the answer would be ‘Charles Choo-Choo Justice’—hands down, no questions.”

Sadly, Woody’s worst nightmare came true . . . for Charlie, it was his final visit to a special place.

Epilogue:

On October 18, 2003, Duke was preparing to play Wake Forest in Wade Stadium in Durham, when long-time “Voice of the Blue Devils” Bob Harris took time during his broadcast to say:

I know it’s homecoming in Chapel Hill, but there’s a gray cloud hanging over the football program because of the death of the greatest player to ever wear the Carolina colors. Charlie Choo Choo Justice has passed away in his hometown of Cherryville. He will be missed by not only the Carolina folks, but all of us who knew him.

Missed indeed. Beautiful autumn Saturdays in Kenan Stadium would never be the same.